Shortly after I’d received my PhD on Bette Davis and the Ambiguities of Gender and before I published my first scholarly article in the journal Screen (‘Masquerade or drag?’), I was invited by the BBC to take part in thirty minute radio documentary on the incomparable though very imitable Mae West. This was for Radio 4’s arts programme Kaleidoscope, presented by Christopher Cook, one of the truly great voices of British radio.

While I got to say a little bit about the way Miss West performed in her movies like a drag queen and walked like John Wayne, the limelight was well and truly stolen from me by movie star Kathleen Turner and drag artiste Lily Savage (Paul O’Grady). Nevertheless, it was a thrill to be in their company and to hear my voice (however much it made me cringe) on BBC Radio 4 in the documentary When I’m Bad, I’m Better (1994).

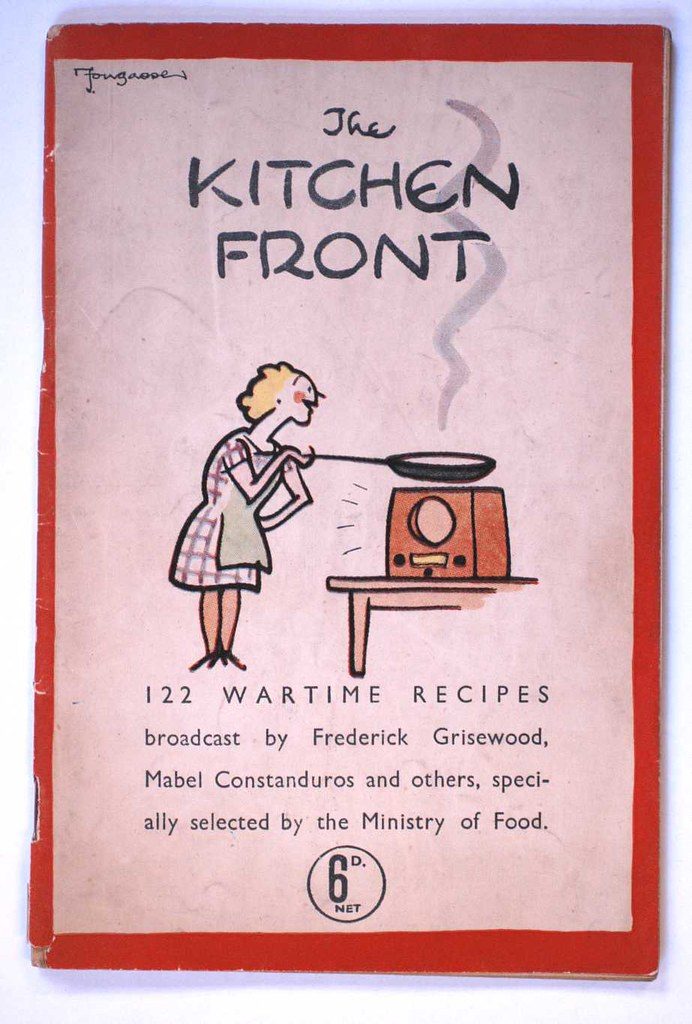

It was another ten years or so before the BBC invited me once more onto the airwaves – I clearly hadn’t made much of an impression the first time round! This time it was to talk about one of Britain’s pioneering radio broadcasters, Mabel Constanduros, who had created the Buggins family comedy sketches in the 1920s, among many other things. Despite the fact that she had devised the first sitcom and soap opera on the BBC, this multitalented actress and playwright was hardly more than a footnote in most standard histories of British broadcasting. I was therefore delighted to be involved in this programme, which set out to celebrate many of the achievements of this major but much neglected figure in broadcasting history, including her development and presentation of a wartime cookery programme on BBC radio to help people cope with the restrictions of food rationing.

The Late Mrs Buggins was presented by the actress Linda Bellingham (perhaps best known for her Bisto TV ads) and broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in April 2005. Three years later, I got to discuss the work of Mabel Constanduros once again, this time for an hour-long programme on the history of radio comedy that was broadcast on a Saturday evening in October 2008 as part of Radio 4’s Archive Hour series. For this, I discussed how Mabel put working-class voices on the BBC in the mid to late 1920s, a time when well-spoken Received Pronunciation had become the order of the day, as decreed by Director-General Sir John Reith.

Presented by Nicholas Parsons, this programme included a strong line-up of radio talent, including Just a Minute‘s Paul Merton and Goodness Gracious Me‘s Sanjeev Bhaskar. This was later repeated (to my surprise) on the morning of Christmas Day that year. It was a highly informative and entertaining examination of how radio comedy had been used in Britain since the 1920s to not only reflect but also influence social change on a wide range of issues – including class, sex, gender and race – hence the not-so snappy title ‘How Radio Comedy Changed a Nation.’

For more on this programme, see the following article in the BBC News magazine: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/7676195.stm

2008 was my big radio year. In addition to teaching lots of courses on radio (theory and production, drama and documentary) at the University of Sunderland, I appeared in three separate BBC radio programmes. Three in one year was a record for me. This was also a big year for Bette Davis as it was the centenary of her birth. One Thursday morning in May, a month or so after the late Miss Davis’ 100th birthday, I appeared in a 30 minute radio documentary entitled Bette in Britain, which was about her trips to the UK from the 1930s to the 1980s, to appear in movies such as Another Man’s Poison (Rapper 1952), The Scapegoat (Hamer 1959), The Nanny (Holt 1965), The Anniversary (Ward Baker 1968), Connecting Rooms (Gollings 1971) and Madame Sin (Greene 1971), as well as to perform in her one-woman stage show in 1975 and, towards the end of her life, to promote her book This ‘N’ That (1988).

Bette in Britain was presented by the British actress Susan George (who insisted on calling Miss Davis ‘Bet’ instead of ‘Bet-tee‘) and the documentary featured a diplomatic contribution from Joan Collins, who’d not had a great experience when working with Davis on The Virgin Queen (Koster 1955) at Twentieth Century-Fox in the mid-Fifties.

My favourite contributor to this programme, however, was the actress Wendy Craig who seems to have had a splendid time making The Nanny with Davis in London in 1965 and describes her Hollywood co-star as not only “charming” but also kind, lovely and generous. One of the most poignant moments in the documentary is when Craig describes how Davis recalled the way in which she had struggled to feed her adopted daughter Margot as a young child. My own contributions to this programme, it must be said, were few and far between, mostly describing Davis’ court case with Warner Bros. at the High Court of Justice in London in October 1936. However, I did pop up again at the very end talking about Davis’ determination to go on working to the bitter end despite her fragile state of health and the ravages of old age.

As much as I enjoyed listening to Bette in Britain when it was broadcast, for me the radio highlight of 2008 was my participation in a discussion of Miss Davis’ stormy relationship with Hollywood rival Joan Crawford and their work together on the remarkable What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Aldrich 1962).

Talking about Davis and Crawford’s famous feud is always fun but to do so live on air on Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour in the company of presenter Jenni Murray and radio legend Anna Raeburn was a tremendous privilege and I had to keep pinching myself throughout this broadcast to make sure that I really was sitting in a studio in Broadcasting House with these two radio goddesses on either side of me and not just dreaming. It’s one of those moments that I’ll cherish for the rest of my life.

I met Anna Raeburn in the foyer of Broadcasting House a little while before we were ushered into the Green Room to await our call to join Ms Murray in the studio. I recognised her immediately despite the fact that the iconic short cropped dark hair was now as silver as my own and much longer. Taking the plunge, I introduced myself as Bette Davis and said that I presumed that I was speaking to Miss Crawford. Thankfully she laughed and took to me instantly, talking to me all the way up in the lift, along the corridor to the Green Room and on into Jenni’s studio. As we entered her domain, Jenni shot us both a look over her glasses that silenced us. She looked resplendent in her turban and undiminished by her recent bout of chemotherapy. I managed to avoid tripping over the crutch that lay across the floor while making my way, as directed, to my seat at the round table with the large BBC microphone at the epicentre of it. In truth, I was completely overawed at the prospect of being on air with these two great exponents of live radio and I can vividly recall the pounding of my heart, especially when Jenni informed me that she was going to ask me the first question. “Please don’t!” I thought to myself. “Just talk to Anna and I’ll sit here quietly and look and learn as much as I can while you both do what you’re so remarkably good at doing.”

I think Jenni realised just how nervous I was sitting there like a startled rabbit in the headlights facing that huge microphone and waiting for the light to change colour. As we listened to some archive interviews of Davis and Crawford, Jenni turned to me and cracked a joke about how petrified she was when interviewing the redoubtable Miss Davis in 1987 and then, the moment our laughter subsided, we were on air and Jenni was asking me the fateful first question about Davis’s initial reputation as the ‘Little Brown Wren’ … and we were off. What followed was twelve minutes of pure delight for me as I chatted intimately with these two great British broadcasters like friends of old about two of Hollywood’s greatest stars and adversaries. This really was the stuff of dreams.

I knew that I was in the hands of a consummate professional by the way that Ms Murray put me at ease and dispelled my tension with laughter. With Anna Raeburn sitting across the way from me, I soon relaxed and began to enjoy myself, safe in the knowledge that we were going to have a wonderful conversation about something we were all genuinely interested in. The respect for Davis and Crawford, especially their work together on What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, was authentic and palpable. Our laughter throughout this intimate roundtable discussion was also genuine.

Jenni Murray turned out to be a great ‘straight man’ in that she fed me with lines so that I could deliver the punchline and, I have to admit, I seized the opportunity to not only display my knowledge of Bette Davis but also to camp it up, especially when we inevitably got on to what the author Shaun Considine calls the ‘divine feud’ in the title of his book on Davis and Crawford. Here, I described Considine’s Bette & Joan: The Divine Feud (1989) as not only a ‘gay Bible’ but also the ‘greatest story ever told.’ I’ve no idea how listeners at home responded to such blasphemy but Jenni and Anna were ecstatic. Jenni’s approval meant a lot to me, although her greatest gift to me came towards the end of our segment when Anna and I were asked to name our favourite films featuring our respective stars. Anna surprised me by citing Grand Hotel (Goulding 1932) rather Mildred Pierce (Curtiz 1945). My choice of Now, Voyager (Rapper 1942) would have come as no surprise to anyone who knows me. To be able to extol the virtues of Davis gaining the stars in the final scene of this great romantic drama felt light a real highpoint for me and it was an opportunity that I relished. Suddenly, it was all over. On the one hand, I was hugely relieved that I’d neither dried up live on air nor made a complete fool of myself. On the other hand, I was disappointed that this unique occasion was over so soon as I could easily have gone on chatting about Davis and Crawford for ages.

Thankfully, Ms Raeburn took pity on me and led me off to a cafe nearby so we could continue our conversation and get to know each other better. It was the start of a ‘beautiful friendship’ – to quote actor Claude Rains at the end of Casablanca (Curtiz 1942) – one that included us doing a public conversation about Joan Crawford’s performance in Mildred Pierce (Curtiz 1945) in Bristol in October 2012 and writing this up into an article for Screen the following year.

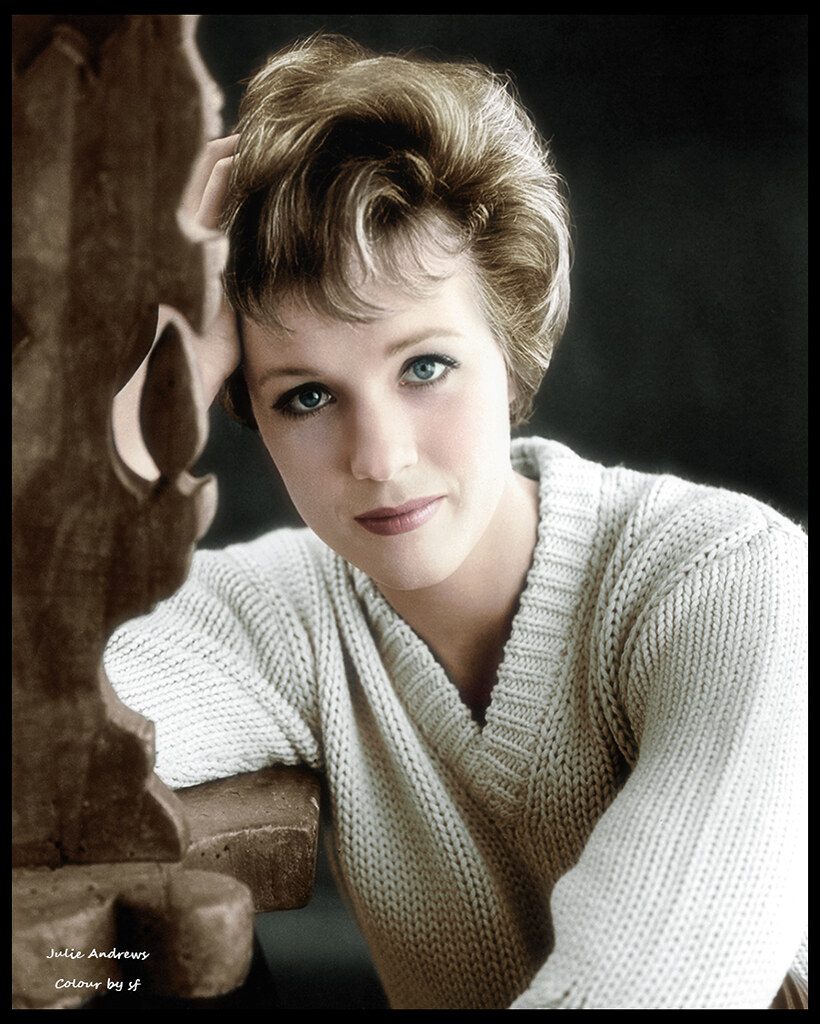

While I got to see a lot more of Anna after our first encounter on Woman’s Hour on the 2nd April 2008, I only saw Ms Murray once more when invited to join her in the studio at BBC Manchester to talk about straight women as gay icons on Woman’s Hour at the end of 2010. Although invited to discuss Bette Davis’ gay following, I found myself answering Jenni’s questions about Judy Garland, Julie Andrews and Madonna. Joined by Freya Jarman of the University of Liverpool, who spoke eloquently of distinctively lesbian fascinations with high profile straight women, we were able to come at this topic from several different angles. While Freya honed in on the importance of power in the iconicity of these female stars, I dwelt on issues of performativity (Davis), pain (Garland) and androgyny (Andrews).

Once onto the subject of Julie Andrews in her iconic role as Maria in The Sound of Music (Wise 1965), I just couldn’t resist the urge to regale Jenni with some of my favourite lines from Rogers & Hammerstein’s song My Favorite Things, including those famous raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens, as well as brown paper packages tied up with string. Ostensibly, the purpose of this was to indicate how Julie had taught generations of gay men to endure ritual humiliation by taking comfort in the pleasure of small things. It was a golden opportunity and I’ll be forever glad that I took it given the look of sheer delight that it produced on Ms Murray’s face. Yet when Jenni asked me to explain gay men’s fascination with Madonna, I was momentarily thrown, given that I’m far from being an expert on pop music. Thankfully (and just in the nick of time), I recalled Madonna’s lines in her song Vogue and her citation here of Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich and other Hollywood female icons, which enabled me to claim that the singer was self-consciously taking up the gay icon baton from these movie queens in her 1990 hit record.

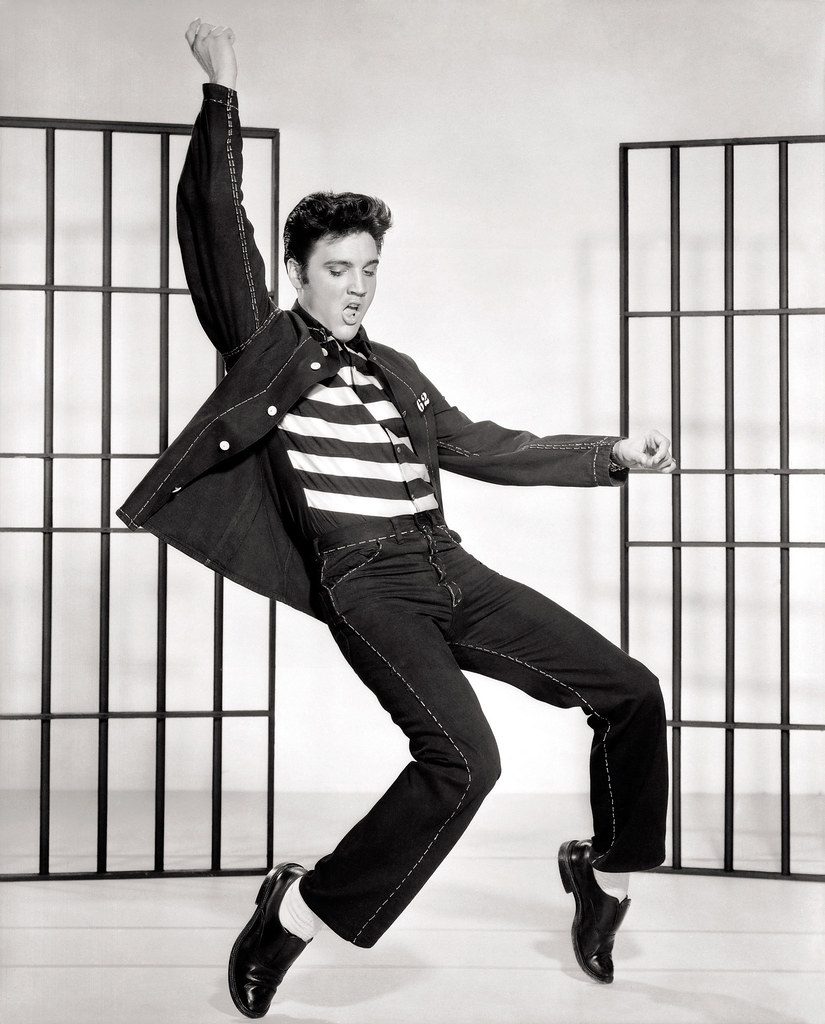

Yet what had Jenni, Freya and myself all excited at the end of our conversation was the thought of Elvis Presley as an icon with almost universal appeal to men and women, whether gay or straight. For Freya, it was his beauty and his physical resemblance to Michelangelo’s statue of David that mattered most. Whereas for me, it was his hips.

This broadcast can be accessed online on the BBC Woman’s Hour archive here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/food/programmes/b00wdk2v The Gay Icons segment starts at c. 31 minutes into the programme.

Despite the enduring appeal of Elvis’s hips, it wasn’t a Presley picture that made a deep impression on me. The movie that changed my life as an impressionable gay man in the mid-1980s was Now, Voyager (Rapper 1942), starring Bette Davis with Claude Rains, Paul Henreid and Gladys Cooper. My first sighting of this classic Hollywood melodrama had a profound impact upon on me when it was screened as part of my degree in the History of Modern Art, Design and Film at Newcastle Polytechnic. At first, I laughed at it, particularly at the sight of a frumpy beetle-browed Bette Davis in flat shoes and spectacles. Yet I was quickly seduced by its magic, including its romance, lush orchestral score, superb cinematography and fine acting. Yet more than anything, it was Charlotte Vale’s struggle to gain independence and love that won me over. Once Davis’ character had undergone a makeover and developed sufficient confidence to stand up for herself to claim what was so rightfully hers, she became someone I could identify with in spite of the fact that I was neither a thirty-something spinster nor a well-born Bostonian.

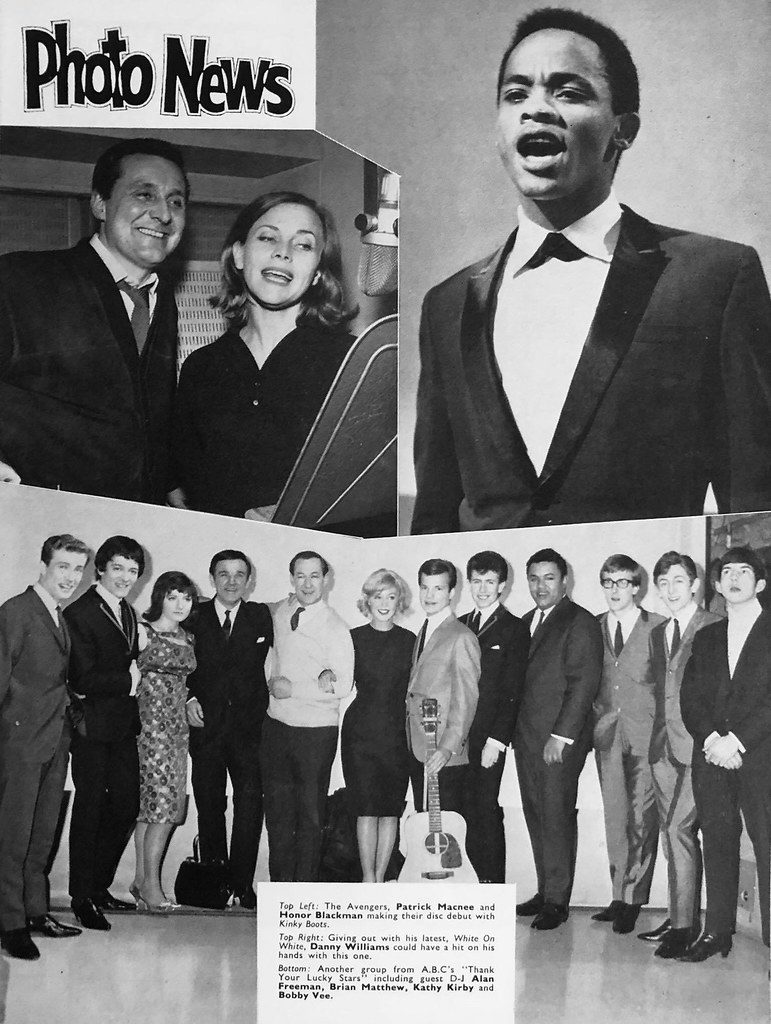

After Now, Voyager had introduced me to Bette Davis and her films while providing me with some kind of template for living, I understood only too well how a movie could change someone’s life and inspire them to adopt a very different path than the one that seemed to stretch out before them. So I was delighted to be invited to take part in a radio documentary in 2009 that was part of BBC Radio 2’s series The Movie That Changed My Life. The movie in this case was All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz 1950) and the life in question was that of the British actress Honor Blackman.

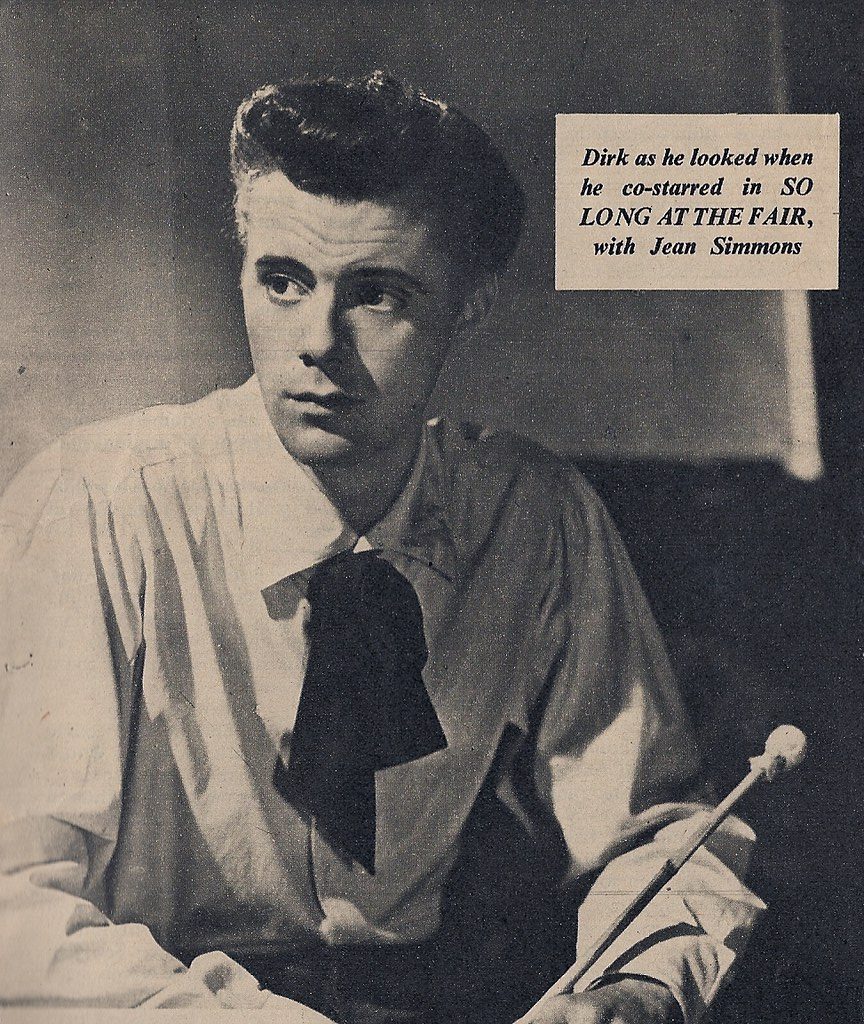

In this programme, Ms Blackman described how she’d been enamoured with Mankiewicz’s multi-Oscar-winning movie as a young aspiring actress, more than ten years before she achieved global fame as Pussy Galore in Dr. No (Hamilton 1964) alongside Sean Connery’s James Bond. At the time, she was a Rank starlet performing supporting roles in films like So Long at the Fair (Farnborough 1950, which starred Jean Simmons and Dirk Bogarde.

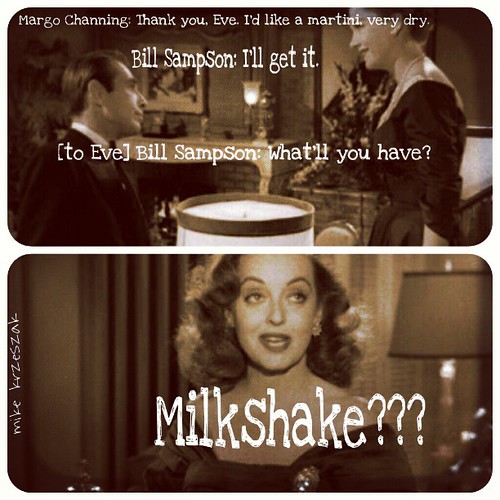

It was her role as Cathy Gale in the trendy TV series The Avengers (1962-64) that transformed Honor Blackman into a household name in Britain, while Pussy Galore made her an international movie star in 1964. As she explains in the radio programme, she didn’t have to scheme and lie her way to the top by displacing older and more established actresses in the way that Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter) does so effectively in All About Eve. She also makes it clear that her enduring fascination with the film lies mostly in its depiction of female solidarity and the strong parts written for women, notably Davis’ Margo, Celeste Holm’s Karen Richards and Thelma Ritter’s Birdie. My part in this documentary was to extol the virtues of the film as a quality production and to note the way in which Eve functions as symbol of perverse female ambition. Later on, I described how Davis’ subsequent marriage to her co-star Gary Merrill proved to be as volatile as their scenes in the movie, while noting that All About Eve ultimately became a camp classic beloved by generations of gay male audiences.

By 2009, I seemed to have found my groove on the radio, talking about gay male fascination with Hollywood’s leading ladies and it gave me pleasure to do so. I loved being involved with speech radio, despite maintaining an aversion to the sound of my own voice. So I was absolutely thrilled in 2017 when invited to take part in Radio 4’s Great Lives after the actress Tracy-Ann Oberman had nominated Bette Davis as the subject of an episode of this long-running series. Following a lengthy telephone conversation with the show’s researcher, it was agreed what topics I would discuss and travel arrangements were made for my journey down to London to record this in the studio with presenter Matthew Parris at Broadcasting House. Seeing my name billed in the Radio Times for this programme was another thrill. The show promised to be as important and as exciting for me as my Woman’s Hour broadcast with Jenni Murray and Anna Raeburn.

Sadly though, it wasn’t to be. I was forced to telephone the BBC a couple of days before the recording to explain with what little voice I had left that I’d been struck down with the dreaded man-flu that left me unfit to travel or croak into a microphone. It was mortifying. Listening to the show when it was broadcast on the 28th April gave me little if any joy. I now count it as one of my great missed opportunities. Yet, in a way, it underlines just how lucky I’ve been to be able to discuss my views on Miss Davis and others over the airwaves, particularly when taking part in radio discussions with so many of my own personal heroines and heroes.

When I watched Now, Voyager for the very first time back in the mid-Eighties as a student in Newcastle upon Tyne, I could not have imagined that I would have so many chances to talk and write about films and film stars or that anyone would have the slightest interest in what I had to say. Being able to bring together my passion for speech radio with interests in movies and movie stars has given me great pleasure over the years. That’s why I rank these appearances on BBC Radio as some of the highlights of my career as a film scholar and historian. As a dedicated listener to Radio 4, it’s been particularly gratifying to have been involved in the making of several programmes for this network. In the end, there’s no point bemoaning the things I didn’t do. After all, I didn’t ask for the moon.

My list of broadcasts:

July 2018 Bette Davis and Celebrity. Live interview with Lisa Shaw, Mid-morning Show on BBC Radio Newcastle.

Dec 2016 Kirk Douglas at 100: Live interview with Simon Logan, Afternoon Show on BBC Radio Newcastle.

Sept 2012 30th Anniversary of the death of Princess Grace (Grace Kelly) of Monaco, BBC World Service (Persian), Dawn, recorded interview.

Dec 2010 Straight Women as Gay Icons, BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour, live studio discussion with Jenni Murray.

August 2009 The Movie That Changed My Life: All About Eve, BBC Radio 2, (contributions to a 30’ radio documentary on Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s film All About Eve, 1950)

October 2008 How Radio Comedy Changed a Nation, BBC Radio 4, the Archive Hour (contributions to a 60’ radio documentary on the history of radio comedy)

May 2008 Bette in Britain, BBC Radio 4 (contributions to a 30’ radio documentary on Bette Davis)

April 2008 Joan and Bette, BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour, live studio discussion with Jenni Murray and Anna Raeburn to mark the centenary of the two stars.

April 2005 The Late Mrs. Buggins, BBC Radio 4 (contributions to a 30’ radio documentary on Mabel Constanduros)

August 1994 When I’m Bad, I’m Better, Kaleidoscope Feature, BBC Radio 4 (contributions to a 30′ radio documentary on Mae West)

Comments are closed for this post.