Davis was different

Back in 2008, Bette’s centenary year, Christine Gledhill and I published an article entitled ‘Bette Davis: actor/star’ in Screen. Here we pointed out that most actors became stars in studio era Hollywood by playing a limited repertoire of character types, and by acquiring a consistent star persona from one film to the next. But Davis was different. Rather than consistently play herself on screen, she created a diverse gallery of screen characters that showcased her versatility as an actor. This made her an unusual star, one famous for the roles she played on screen and for being a talented actor rather than for the intricate details of her personal life.

There’s certainly no doubting the fact that Davis was a major Hollywood star by 1940, with a string of box-office hits behind her and a legion of die-hard fans on both sides of the Atlantic. She also had a distinctive star image as a feisty, rebellious, strong, independent, ambitious, hard working, unconventional woman. Yet, as Christine Gledhill and I argued in our essay, Davis used her image as a great actor to conceal more personal aspects of her personality and personal life, maintaining a distance between her self and her fans, as well as her self and the characters she played on screen. Davis’s on-screen characters seldom gave her fans access to her real or private self, we argued.

Since 2008, I’ve often wondered about this, asking myself if we’d neglected to fully recognise the extent to which Davis’s celebrity beyond her film roles provided her fans with greater access to her personality. And so the time has come to revisit this question by considering Bette Davis not only as an actor and a star but also as a celebrity.

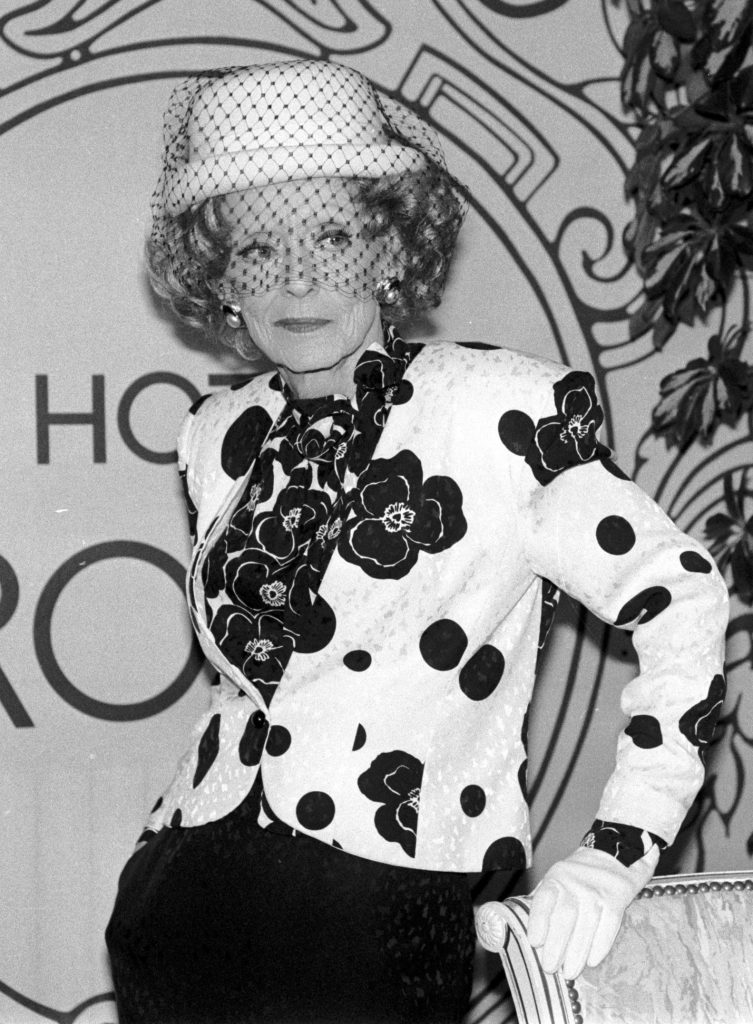

Looking at the final decade of Davis’s career (the 1980s) certainly reveals that she was a major celebrity consistently profiled in the press, magazines and on television, talking opening to journalists and TV chat hosts about various aspects of her private life. Now I’m wondering if celebrity was a major facet of her work as a star at a much earlier stage of her career. It’s something that I need to pay more attention to.

The essay ‘Bette Davis: actor/star’ that Christine Gledhill and I published in Screen in 2008 can be accessed online and purchased form Oxford University Press here https://academic.oup.com/screen/article-abstract/49/1/67/1637566?redirectedFrom=PDF. Just click on this web address and it’ll take you straight through to the site where you can access it.]

Where do I begin?

A starting point might be the moment Bette Davis arrived in Hollywood in 1930 after signing a contract with Universal Studios following a short but successful spell on Broadway. She was neither a star nor a celebrity at this time. And to prove this point Davis often told the tale of how her arrival at the railway station in Los Angeles went unrecognized by the person sent to meet her from the studio. Her first nine months in Hollywood were a disaster, and after performing in supporting roles in six films, Universal terminated her contract. She was on the point of returning to Broadway, when Warner Bros. offered Davis a one-picture deal to play a supporting role in a George Arliss film (see chapter 5 of When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 for more details of Arliss’ mentorship of the young Davis).

At the start of 1932, Davis was offered a 5-year option contract with Warner Bros., initiating an 18-year association. She spent the next two years at Warners as a lowly contract player, appearing in minor and supporting roles. Several attempts to star her in films created a string of box-office flops. Despite giving her a Hollywood-style makeover, the studio failed to turn Davis into a viable glamour queen.

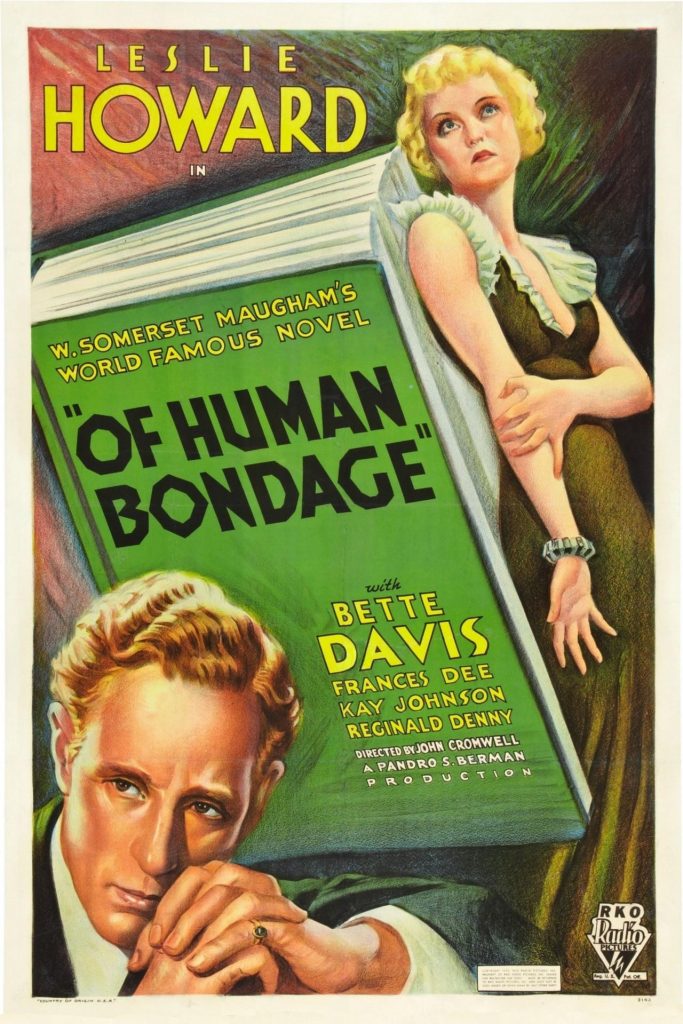

But in 1934, Davis attracted critical attention with an uncompromising performance opposite Leslie Howard in Of Human Bondage at RKO. Some reviewers predicted that she’d win an Oscar and when she failed to be nominated, a write-in campaign was launched to persuade the Motion Picture Academy to change its mind. Although the Academy stubbornly refused to budge, Davis gained a considerable amount of publicity and sympathy among moviegoers and movie magazine readers, significantly raising her profile.

Bette explodes

Her attempt at seduction has failed. Suddenly she seems pathetic, vulnerable and, for a brief moment, almost angelic. But when told that she disgusts him, a dramatic transformation occurs. In close shot, her face registers shock, her eyes wide and staring. Her jaw moves very slightly forward and her eyes glare with hostility as the first words spew from her mouth, launching herself into an hysterical tirade that gathers speed and volume with every word. Her eyes flare open and her arms jerk in spasms at her sides before she turns around abruptly as if to walk away only to immediately spin back round and resume her vocal assault. Her mouth bites viciously on every word, getting faster and louder still, while her arms break free and her tightly clenched fists jab out to beat the air in front of her.

She retreats, turning away but instantly spins back again, thrusting herself forward to declare, ‘and after you kissed me, I always used to wipe my mouth.’ Her eyes flare, at his feet, at his face. ‘Wipe my mouth’, she repeats, literally wiping her mouth with her forearm and violently throwing the offending kiss to the floor with a repulsive gesture. She screams her next words, her in-takes of breath being clearly audible, before she grabs a plate and flings it to the floor where it smashes. ‘D’you know what you are, you gimpy-legged monster? You’re a cripple, a cripple, a cripple!’ These words are so high-pitched that her voice breaks, producing a shrill sound, both piercing and fragile. With the last word out of her mouth, she gazes around for an instant and then dashes from the room, slamming the door behind her. Her tirade has taken just over a minute. It is powerful, shocking and intense, a bravura display of hysteria, fury and bitterness, edged with vulnerability.

This is not Davis in a rage but an actress in motion, presenting fury through her shoulders, neck, torso, her arms and hands, her eyes and her mouth, through her voice and her breathing. Fury is the result of a systematic orchestration of all of these elements, developed through the use of muscles, movements and sounds. The scene reveals an actress in full command of her body, face and voice, whose movements are used to convey the thoughts and emotions of her character in a most vivid way. This is Bette Davis’ most dramatic performance in Of Human Bondage (John Cromwell, Radio Pictures, 1934), one that reveals techniques she had developed as a student of dance and drama and as a professional actor of stage and screen, techniques that she would later perfect and refine. It is a defining moment, when Bette Davis proved what she was truly capable of as an actor.

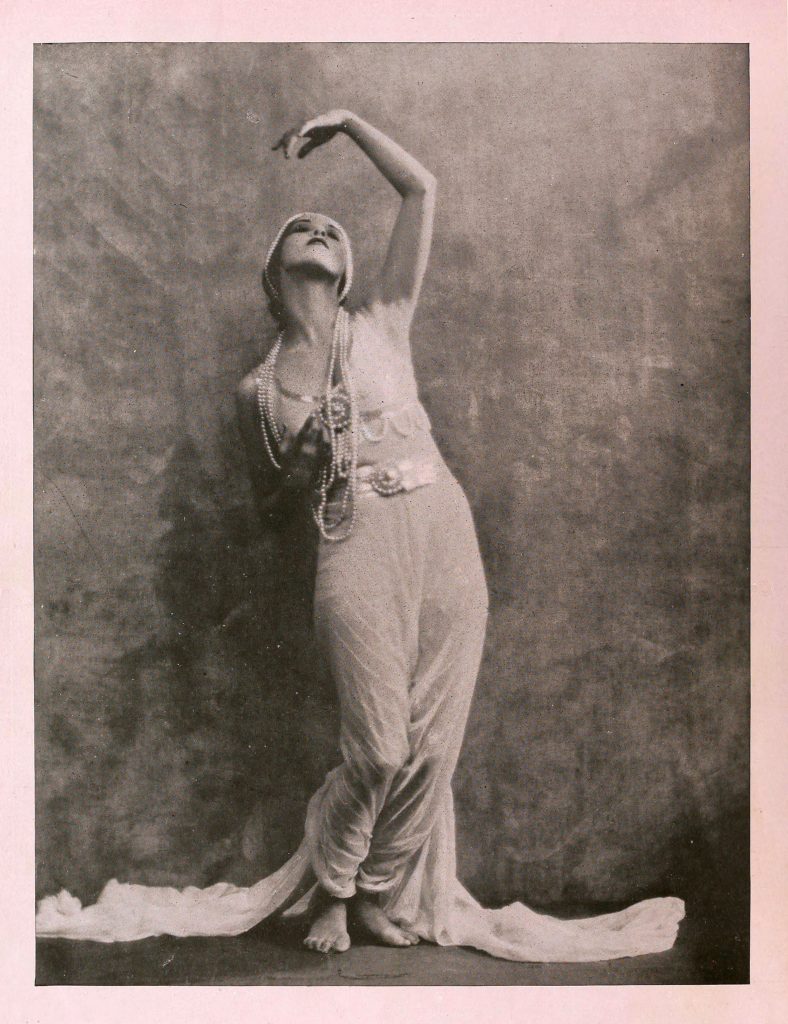

Back in October 1927, as a full-time student at the John Murray Anderson and Robert Milton School of Theatre and Dance in New York City, Bette Davis had attended the classes of Martha Graham, pioneer and leading exponent of modern dance.

One of Graham’s foremost principles was that to dance was to act, alerting her pupils to the expressive potential of the body. Her technique centered primarily on achieving control of the back and the pelvis. Having developed a remarkably expressive use of her spine, neck and shoulders as well as her arms, Graham developed these in her pupils by having them begin their training seated on the floor. Working only with their arms and torsos, her students concentrated on strengthening and refining the movements of their bodies from shoulders to hips.

Throughout her film career, Bette Davis was to draw repeatedly on many of the expressive techniques she had acquired during her dance lessons. This is most often to be seen in the way she concentrates her performance specifically on the movements and tensions of her shoulders, torso, hips and arms. For instance, her tirade in Of Human Bondage involves her body registering a sequence of changes that entail her shoulders descending, her arms becoming increasingly animated, her hands becoming increasingly tense, her body hesitating between pulling away and thrusting forward, producing two full body spins. This is the product of an actress trained in the art of expressive movement and, more specifically, in the Graham technique. Another actress may have performed the whole scene with nothing more than her voice and her face, making her eyes and her lips register all the anger, hatred and loathing felt by her character. But this is not Davis’s approach.

For Davis, it is not enough to tell a man that she despises him so much that she always wiped her mouth after he kissed her. To express the full extent of her disgust, she has to physically wipe her mouth and violently fling the imagined kiss away from her. In this and other ways, every part of her must express the mounting hysteria unleashed by her words, creating what appears to be involuntary movements of the body, spasms running through her, which make her seem out of control. Yet, of course, this is a highly controlled performance, one that is deftly orchestrated, building steadily with repeated gestures, movements, muscle tension and expressions. Each action is carefully deployed in relation to the other, gradually increasing the pace and the scale of each action as it is repeated until she reaches a climax on the words ‘cripple! cripple! cripple!’.

Of Human Bondage, shot in February and March 1934, was the actress’ twenty-second picture and her most important role to date: a leading role, playing opposite the acclaimed English actor Leslie Howard. While Howard had greater screen time devoted to him, as the bigger star at this time, it is Davis that attracts the most attention during their scenes together. The camera follows her, even when she is doing no more than walking across the room to open a door, while strategically placed mirrors are frequently used to emphasize and duplicate images of her body. If the framing and mirroring of Davis focus attention upon her body, so does the actress’ own unceasing movements. Where Howard is often static or slow moving, she is all restless motion. When Bette Davis walks, it is not just her legs that move but also her shoulders, her hips, her arms and her fingers.

Bette Davis produced an electrifying performance when on loan to RKO to support Leslie Howard in Pandro S. Berman’s production of Somerset Maugham’s novel Of Human Bondage. Aided and abetted by director John Cromwell, she not only employed a full-bodied performance style but also crafted an extraordinary voice. Indeed, this was one of the most striking aspects of her characterization, primarily due to the accent she adopts for her role as the common Cockney waitress with ideas above her station. For instance, at the start of her hysterical tirade, when she declares in astonishment, ‘Me! … I disgust you! … You!’, she pronounces the word ‘you’ as ‘yew’ with an emphasis on the ‘w.’ Despite the apparently mannered quality of her speech, the actress was aiming for both subtlety and realism here, being determined to avoid stage Cockney or any other form of exaggerated imitation. Essentially, Davis wanted Mildred Rogers’ voice to betray her as a fake, as someone with pretensions to grandeur despite her working-class background. To achieve this, she risked making her accent sound false. The challenge for a young American actress of performing with a Cockney accent opposite an English actor was great enough. To create a voice that was both authentically Cockney and working-class while also sounding fake due the character’s failed attempt to sound ‘high class’ added significantly to the challenge. Yet it gave Davis a rare opportunity to display her vocal skills, as well as her ambition and intelligence as a screen performer.

[The above is taken largely from my essay ‘Bette Davis: Malevolence in Motion’ in Screen Acting (eds.) Alan Lovell and Peter Kramer (London:Routledge, 1999), pp. 46-58.] An eBook can be purchased from the publisher’s website at https://www.routledge.com/Screen-Acting/Kramer-Lovell/p/book/9780415182942

Acting dangerously

In 1935, Warners cast Bette Davis in the leading role in Dangerous (Alfred E. Green) playing Joyce Heath, a washed-up, alcoholic stage actress rescued from the gutter by the socialite Don Bellows (Franchot Tone), who subsequently falls in love with her while trying to resuscitate her acting career. There was no better way of establishing Davis’s credentials as a brilliant screen actress than by having her play a gifted (if self-destructive) thespian. There was no better way of maximizing Davis’s screen theatrics than to cast her as a theatrical character. Of course, the prospect of playing a woman supposed to be one of the American theatre’s most talented stars was a daunting one, and one that would make or break Davis in the eyes of the critics and the public. On all counts, Dangerous marked the achievement that Bette Davis had long been hoping for. It proved to be her first star vehicle to succeed with audiences and also win her an Oscar for Best Actress in a Leading Role.

It is clear that at the time she made this film Davis’s voice was developing into something distinctly her own. Her accent is clipped and classy. She speaks quite fast and quite loud, projecting her voice, except when it is checked, held back in her throat to produce a voice choked with emotion. For instance, when Don Bellows discovers Joyce crying on a bed, Davis’s voice is typically fast, loud and clipped but then it suddenly drops, softens and slows to prepare us for the most critical moment of the speech, “When you took me in your arms I didn’t want to laugh.” In speaking this line, Davis created an unusual moment of intimacy, not just between herself and her co-star but also with her audience. She did this by simultaneously softening her voice, slowing the pace and reducing its projection.

Towards the end of Dangerous there is a scene that is strikingly reminiscent of the one described above in Of Human Bondage. Joyce visits her estranged husband Gordon (John Eldredge) to persuade him to give her a divorce so that she can marry Don. Initially she is business-like, cold and aloof to the point of becoming visibly contemptuous when she discovers that he still loves her after all she’s done to destroy his life and make him miserable. When he informs her that he will never give her a divorce because she is all he has left, she grows angry and, after a brief and failed attempt at supplication, she finally explodes in fury, hatred and loathing, denouncing her husband as pathetic and repulsive to her.

Joyce’s outburst lasts a little less time than Mildred’s, about twenty seconds, culminating in her slapping her husband across the face. It is shot in a single static, high-angled close-shot up to the point just before she slaps him. In many ways this is a similar scene to Mildred’s ugly tirade against Philip Carey (Leslie Howard) and, as one might expect, Davis uses her body, eyes, mouth, hands and voice in similar ways. Many of the techniques she used in Of Human Bondage are used here but in miniature. There’s certainly no grand throwing away of an imagined kiss, no miming of a memory or thought. There’s simply not the scope for such gesturing. Throughout the tirade the actress’ body is restricted, pinned to an armchair and tightly framed, allowing her no backward or forward movements and no full body spins. The relentless close-shot means that not only is her body out of sight (torso and hips especially) but also the movements of her head are forcibly kept to a minimum. Unable to use her full body, she compensates with a more emphatic use of her eyes. Meanwhile, her brow, neck and shoulders form a communicating link between her face and her fingers.

What is particularly striking about the tirade in Dangerous is the relationship Davis establishes between her eyes and her fingers as the speech progresses. As her speech gathers speed and volume while rising in pitch, her flaring eyes produce a corresponding flinching of the fingers. Increasing agitation forewarns of the inevitable slap she is to deliver as her climax. This means that despite the whole thing being filmed in a static close-shot, there is nothing static about this performance. On the contrary, there is constant movement despite the fact that these movements are restricted. Produced under restraint, Bette Davis was forced to concentrate upon nuances rather than grand gestures. Unable to step back from the camera and launch into a full-scale theatrical assault, she reduced each gesture and movement to the most telling, dispensing with anything that did not add new meaning. The camera’s relentless scrutiny of every detail of her performance did the rest for her.

Davis’s tirade in Dangerous demonstrates her greater finesse and subtlety but also her greater reliance upon the technology of cinema. The camera’s ability to register and project minute movements and expressions is used to maximum effect here. What has gone is the attempt to project thoughts and feeling via elaborate physical action. It is not that she ceases to use physical movement to express her character’s every thought and feeling but rather that muscle tension and tiny movements of eyes and fingers convey as much (indeed more than) an arm thrown out from the body or a writhing torso, all of which are registered and revealed by the camera. Under restraint, Davis produced a much finer and more affective screen performance in Dangerous that avoided some of the excessive (even hammy) qualities of her tirade in Of Human Bondage.

Yet, despite commercial success at the box office and an Academy award for her performance in Dangerous, Davis’s acting met with a mixed response from the New York critics. For instance, André Sennwald described her in the New York Times on the 27 December 1935 as being “Best under taut restraint” (p.14). “Miss Davis” he added, “is least satisfying when her lines lead her to be sputtery and even tearful” (ibid.). This suggested that the actress still needed to perfect her screen acting skills by becoming as effective in the execution of quieter, sadder and more subdued emotions as in her flaming, tempestuous outbursts. And this would appear to have been something that Bette Davis perfected when performing the role of Gabby Maple in The Petrified Forest (Archie Mayo, 1936) some months later, once more opposite Leslie Howard in his star vehicle.

Almost petrified

The Petrified Forest began life as a stage play, written by Robert E. Sherwood in 1934 for the British actor Leslie Howard. It started its lucrative six-month run on Broadway in January 1935, attracting rave reviews in the papers and a nomination for a Pulitzer Prize. A strong supporting cast led by Humphrey Bogart and Peggy Conklin made this one of the most acclaimed productions of the 1934-35 Broadway season. After acquiring the film rights, Warner Bros. hired director Archie Mayo to film Howard and Bogart in their original roles, while Bette Davis was recruited as Peggy Conklin’s replacement.

[For more about the transfer of this film from stage to screen and the star image and understated acting style of Leslie Howard, see chapter 7 of my book When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018).]

The film was shot between mid-October and the end of November 1935, which gave Davis almost no break after making her star vehicle Dangerous. However, what it did give her was a complete change of pace in a part that was strikingly different to her previous roles. This enabled her to reveal a much quieter side of her persona. For the part of Gabby Maple, she reigned in her histrionic skills and performed without the pyrotechnics now so familiar to moviegoers and critics. Her role called for a quiet and charming innocence, although one that hints at a stronger and more independent personality beneath the surface.

Although Gabby is a pretty young thing and a dreamer, she also has a core of steel. A wandering penniless intellectual, Alan Squier (Howard), is struck not only by her youth and beauty but also her ruggedness, which includes the coarseness of her language, her strange naivety, the primitivism of her paintings, the fierceness of her desires and her impulsiveness. A pragmatist, she is unconventional and modern by the standards of mid-Thirties America, driven by a desire for self-fulfillment rather than duty or virtue to the point of being amoral in terms of her sexual assertiveness, marking her out as more feminist than feminine. Her heroism, meanwhile, comes through in the final scenes of the film while cradling a dying man in her arms.

For Howard and Davis, this was their most emotionally charged scene. Here, Gabby holds Alan Squier after he has been shot by the gangster Duke Mantee (Bogart), the pair sitting on the floor beside a bullet-riddled wall. Squier’s death takes a few minutes and is filmed entirely in a medium close shot with both characters facing the camera and unable to see each other’s face. Initially, the pair adopt forced smiles, trying to be brave for each other. However, as Squier slips quietly into death, his speech slows and fades away, while his face and body steadily relax. Davis’s large and liquid eyes register her anxiety and distress as Gabby feels the dead weight of Alan’s body against her.

Despite being such a big scene, it is underplayed by the two actors throughout, concentrating attention on the most subtle of gestures, movements, looks and sounds, involving the audience in an intimate relationship with the two characters at this critical final moment. The protagonists’ confused thoughts and feelings are made perceptible with slight changes in the actors’ breathing, facial tension and vocal intonations. Clasped together and fixed into a seated position on the floor, their body movements are restricted to head and neck, so that attention is focused on the actors’ faces and voices. Breathing takes on a crucial role here. Having been shot in the lung, Squier gradually expires, with Howard taking noticeably shorter breaths. He speaks more softly and in shorter segments as the scene progresses, repeatedly pausing and eventually expiring halfway through his final line. Gabby also struggles to breathe due to her shock, fear and panic but her inner strength is also revealed through the way she persists, remaining calm and collected so as not to disturb the man ebbing away in her arms. Slight gasps for breath and tension in her face and voice suggest a determination to master her emotions and remain in control.

[For a more detailed analysis of this scene and a discussion of The Petrified Forest as a melodrama, see my essay ‘Modernizing Melodrama: The Petrified Forest on American Stage and Screen (1935-1936),’ in Melodrama Unbound: Across History, Media and National Cultures (eds) Linda Williams and Christine Gledhill (Columbia University Press, 2018: 135-150). This chapter can be purchased and downloaded from here: https://www.degruyter.com/columbia/view/book/9780231543194/10.7312/gled18066-011.xml]

When released at the Radio City Music Hall in Manhattan at the beginning of February 1936, Warners’ movie version of The Petrified Forest was greeted with almost unanimous praise from the New York film critics, many raving over the performances of principal actors, as well the fine and literate script and Mayo’s artful direction. William Boehnel, for instance, in the World-Telegram stated on the 7th February that, “the whole thing is played so richly, so rightly that the film emerges as a work of distinction.” What the critics witnessed and appreciated was, among other things, a more accomplished performance from Bette Davis that was now as affective in the quiet scenes as the explosive ones. After working with Leslie Howard on this film, observing his skilful underplaying and adjusting her own performance style down to accommodate his (most notably, in the death scene), Davis had enhanced and enriched both her acting method and her star image.

Marked for stardom

A month after the release of The Petrified Forest, Davis won her first Oscar for her performance in Dangerous, which distinguished her among her peers as both an actor and a star. Yet her films of 1936 were hardly distinguished. Indeed, a series of cheap crime thrillers caused Davis to accept a part in a British film without the permission of Warners’ senior executives, resulting in a much-publicised court case when the studio sued her for breach of contract. This took place in the High Court of Justice in London in October 1936. The judgment eventually forced her to return to Los Angeles to honour her contractual obligations. So far as the court case was concerned, Bette lost. As far as her bid for freedom was concerned, she failed. But, in other ways, she won. Davis actually gained a lot of sympathetic press coverage throughout the court case, particularly in Britain, and also gained many new fans, as well as a new public persona, that of “Battling Bette,” a moniker used by, among others, the British film critic Freda Bruce Lockhart in an article entitled ‘Battling Bette Wins! in Film Weekly on 3rd September 1938 (p. 6). Henceforth, Davis was widely seen as a plucky underdog prepared to take on the big boys of the movie business. Yet the actress realized that she could no longer fight her battles alone. So in the wake of her court case, she hired an agent (Mike Levee), an attorney (Dudley Furse) and a business manager (Vernon Wood). This was Team Davis in the late 1930s, one that helped strengthen her position in the American film industry prior to the outbreak of World War II.

The film in which Bette Davis first appeared after her court case was a supreme compromise, being both a quintessential Warners’ movie with the defining characteristics of the studio stamped all over it and also most definitely a ‘Bette Davis film.’ It was also both a punishment and an opportunity for the actress to give a commanding performance in a role eminently suited to her talents. In Marked Woman (Lloyd Bacon, 1937) Davis was beaten half to death and made to stand up in a court of law in order to convict a powerful leader of a vice and prostitution ring. As in all good Hollywood movies of this period, the oppressed ultimately triumph and the oppressor is brought to justice in the final reel. This could only have been intended as a bitter pill for the actress to swallow, forcing her to go through a courtroom drama yet again. Yet, however humiliating it may have been, it fired Davis’ determination to play the role with nothing less than grim honesty. Her identification with her character struck many reviewers as absolute.

On April 14, the reviewer in Variety proclaimed her to be ‘among the Hollywood few who can submerge themselves in a role to the point where they become the character they are playing’ (p. 12). Whilst this may have been true, Davis’s ability to submerge herself completely in a role was entirely dependent upon being cast in the right kind of part. Marked Woman offered her such a part. For the first time in her film career, Davis was able to perform a character modeled on her own persona, one that was born during the court case with Warners in October 1936, when the world discovered that Miss Bette Davis was willful, rebellious, courageous, determined, ambitious and, above all, a fighter. This was more than just the discovery of a perfect formula for Bette Davis. This was the creation of a film role to exploit and enhance a distinctive star identity.

The reviews of Marked Woman were unanimous in their praise and virtually all of them described the film as a ‘Bette Davis picture,’ while paying relatively little attention to her co-star Humphrey Bogart, whose role was at least equal to, if not actually greater than hers. On April 12, Frank S. Nugent declared in the New York Times that ‘Miss Davis has turned in her best performance since she cut Leslie Howard to the quick in “Of Human Bondage”‘ (p. 15).

A final fling with Leslie Howard

It was in 1937 that Davis had a third and final opportunity to cut Leslie Howard to the quick, this time in the screwball comedy It’s Love I’m After (Archie Mayo). Despite Davis’s checkered history playing comedy on screen, this one worked and delighted audiences and critics alike.

Ever since Columbia had scored a massive commercial and critical hit with It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), Warners had be striving to come up with a surefire romantic comedy of its own and Bette Davis was repeatedly cast opposite the studio’s leading male comic talents in order to attain the studio’s ambition. Despite the best efforts of Davis, William Powell and choreographer Busby Berkeley, nothing could make Fashions of 1934 (Wm. Dierterle, 1934) a hit.

Two years later, George Brent and Eugene Pallette did their best to support Bette Davis in The Golden Arrow (Alfred E. Green) but this proved to be more of a dead duck than a golden goose.

But in 1937, It’s Love I’m After finally gave Warners the hit rom-com it had been hoping for and nothing could be more different than the previous year’s pairing of Howard and Davis in The Petrified Forest. Here, Davis played Joyce Arden, a celebrated Shakespearan actress, performing to great acclaim opposite her fiancé Basil Underwood (Leslie Howard). On stage they are a dream combination, off-stage an absolute nightmare. The movie successfully exploited Davis’s reputation as both a fine actress and as a fighter (‘Battling Bette’). While enabling the leading players to over-act to their heart’s content, the film also incorporated aspects of Davis’s most acclaimed films (notably Of Human Bondage and Dangerous) and, at the same tine, exploited a formula for romantic comedy pioneered by the screwball hit 20th Century, directed by Howard Hawks at Columbia in 1934.

This film had John Barrymore and Carole Lombard as a sparring husband and wife acting team whose marriage is more than a little shaky and whose approach to life, love and work is more than a little screwy, not to mention theatrical. It was a tall order for Bette Davis and Leslie Howard to follow so closely in the footsteps of Lombard and Barrymore but with a great script by Casey Robinson and a terrific supporting cast that included Olivia de Havilland, Eric Blore and Bonita Granville, they just about pulled it off, producing one of the big box-office hits of the year.

Charles Affron later wrote in his book Star Acting (1977) that It’s Love I’m After was a major coup for Bette Davis in 1937 since “she proved herself an accomplished comedienne by extracting the humor from her own caricatural gestures – flapping her arms, prowling over the sets, opening a door as if she wanted to destroy it. By that time she was able to control her persona with self-irony…” (p. 293).

At her peak

By 1938, Davis had proven herself not only capable of great tempestuous rages and quiet restraint on the big screen but also of sparkling, ironic and witty comic playing in order to secure what Variety called a ‘smash hit comedy.’ However, for the next few years, she would attain the very highest levels of stardom and praise for her performances in a string of heavy duty dramas widely referred to at the time as “weepies” and later designated “melodrama” and “women’s pictures.”

The first of these was That Certain Woman (1937) in which, for the first time, Davis was directed by Edmund Goulding and starred opposite Henry Fonda. A remake of Gloria Swanson’s silent movie The Trespasser (Goulding, 1929), this was changed to accommodate Davis’s own unique star image and her acting style. Stepping into Swanson’s shoes indicated that Davis was now operating as a star in Hollywood and, as such, she took the leading role in her own star vehicles, many of which featured the same supporting cast (notably George Brent), directors (Goulding, William Wyler and Anatole Litvak), writers (notably Casey Robinson) and cinematographers (Ernest Haller and Sol Polito). This team was created around Davis to ensure the consistency of her productions and brand image while maintaining a steady output of films to exploit her popularity for as long as it lasted. Some of her biggest and most successful films were made as part of this film cycle, including Jezebel (Wyler, 1938) and Dark Victory (Goulding, 1939), both of which were adaptations of Broadway plays transformed to accommodate the Davis image.

In Jezebel, Davis starred once again opposite Henry Fonda and was supported yet again by George Brent. Her meticulously crafted performance as the rebellious Southern belle as the heart of this film won her considerable praise, along with her second Academy award for Best Actress in a Leading Role.

[For more information on Davis’s performance in Jezebel, see my essay ‘Making an Entrance: Bette Davis in Jezebel,’ in the book Film Moments: Criticism, History, Theory edited by James Walters and Tom Brown (BFI, 2020: 34-37). This can be accessed online here https://www.academia.edu/415071/Film_Moments_Criticism_History_Theory or purchased as an eBook from Bloomsbury here https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/film-moments-9781838715786/]

The following year, Davis was nominated again for the Best Actress Oscar, this time for her role in Dark Victory. Despite losing to Vivien Leigh for her performance in David O. Selznick’s epic Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming & George Cukor, 1939), this was a considerable achievement, especially as she continued to achieve Oscar nominations every year until 1943; namely for her performances in The Letter (Wyler, 1940), The Little Foxes (Wyler, 1941) and Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942).

Films such as All This and Heaven Too (Anatole Litvak, 1940), The Great Lie (Goulding, 1941), Now, Voyager (Rapper, 1942), Old Acquaintance (Vincent Sherman, 1943), Mr. Skeffington (Sherman, 1944) and A Stolen Life (Curtis Bernhardt, 1946) were made at the very peak of Davis’s career. This was when she was known as the ‘Fourth Warner Brother’ due to her pre-eminent position at Warners, her power granted by virtue of her enormous popularity with the women of Britain and America throughout the years of the Second World War.

[For more on this period of Davis’s career, see my essay ‘The Fourth Warner Brother and her Role in the War’ in Journal of American Studies, 30, I, April, 1996, pp. 127-131. This can also be found in Walter L. Hixson (ed.) The American Experience in World War II: Vol. 10, The American People at War: Minorities and Women (NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002). This can be accessed on JSTOR at https://www.jstor.org/stable/27556064?seq=1 or purchased online and downloaded from Cambridge University Press here https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-american-studies/article/abs/fourth-warner-brother-and-her-role-in-the-war/C762896120422D72221305B3685AA562#article]

At the height of her power in Hollywood, Davis hired Lew Wasserman as her agent and he subsequently helped her to renegotiate her contract with Warners in 1944, 1946 and 1949 with increasingly better terms.

As one of Hollywood’s biggest stars of the Forties, Davis regularly featured in movie magazines, often appearing on the covers of periodicals like Photoplay and Modern Screen but also featuring in more general interest publications, such as Life and Ladies Home Journal. She also featured in photo-spreads and appeared in advertisements for products such as cigarettes, Lux soap and Max Factor cosmetics. Her marital breakdowns were regularly cited in the papers, and there were sometimes intimations of relationships with co-stars such as George Brent, with whom she appeared in Jezebel, Dark Victory, The Old Maid (Edmund Goulding, 1939) and The Great Lie. Articles also reported her rivalry with fellow actresses like Miriam Hopkins, with whom she appeared in The Old Maid and Old Acquaintance. Another recurring theme was Davis’ struggle to maintain a high-level career whilst also being a wife and homemaker. When presented at home, Davis was often seen in casual and even rather masculine clothing, and reports of her ‘private life’ frequently pictured her as anything but glamorous, favouring the countryside over the city, nature over high society, and her dogs rather than showbiz celebrities. She was also closely associated with her hometown of Boston and presented as a no-nonsense down-to-earth New Englander rather than a Hollywood glamour queen. Such reportage, however, means that press coverage and publicity did put aspects of Davis’s private life and personality into public circulation, making her one of America’s leading celebrities during War World II.

It was in 1943, at the height of the war, that Joan Crawford left MGM and joined Warners Bros. However, she didn’t star in her first Warner picture until 1945. This was Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz), a movie that transformed her into an Oscar-worthy actress capable of challenging Bette Davis in the dramatic acting stakes. Much to Bette’s shame and fury, Crawford’s subsequent hits consistently did better box-office and garnered better reviews and award nominations than her own.

After the war

After the end of World War II, Bette Davis’s career began to decline as a new generation of actresses vied for her crown as the queen of Hollywood. Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner enjoyed greater success with their films than Davis after 1946. They also stole the headlines in the papers and on the covers of the magazines.

After the birth of her first child (Barbara, aka B.D.) in 1947, Davis’s work schedule diminished, giving her more time to concentrate on childcare. She made no films in 1947 and only two in 1948. Neither did well at the box-office or at the Oscars. Davis made just one more film for Warner Bros., which was in 1949, and then the studio terminated her contract.

[For more on Davis’s extraordinary and much derided performance in Beyond the Forest, see my essay ‘The Naked Ugliness of Beyond the Forest (1949),’ in Naked Exhibitionism: Women, Gendered Performance and Public Exposure (eds.) Claire Nally and Angela Smith (I.B. Taurus, 2013). This book can be purchased from Bloomsbury here https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/naked-exhibitionism-9780857724922/]

At the age of forty-one, Davis became a freelance actor, relying on her agent to find her work. Her first project was a starring role at RKO in Story of a Divorce, later released in 1951 as Payment on Demand. In the meantime, Twentieth Century-Fox hired her for a leading role in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve. Here, she stole the show with a career-defining role as ageing Broadway diva Margo Channing. Though the part hadn’t been written for her, Davis proved to be a ‘perfect fit,’ producing perhaps the greatest performance of her career. It certainly won her a New York Critics Award and an Oscar nomination.

All About Eve also provided Davis with her fourth and final husband, Gary Merrill, who played her love interest in the movie. However, even though the film was a box-office hit, it didn’t really stop the decline in Davis’s career.

[For more on All About Eve, see my essay ‘Interpreting All About Eve: A study in historical reception’ in Hollywood Spectatorship: Changing Perceptions of Cinema Audiences (eds.) Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby (London: BFI, 2001), pp. 46-62. An eBook can be purchased from Bloomsbury here https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/hollywood-spectatorship-9781838716233/]

Davis did more parts at Twentieth Century-Fox in the early Fifties, supporting husband Gary Merrill in Phone Call from a Stranger (Jean Negulesco, 1952) and starring in The Star (Stuart Heisler, 1952) as an ageing movie queen and former Oscar-winning actress on the skids.

After being cast in a leading role as Elizabeth the First of England, Davis transformed The Virgin Queen (Henry Koster, 1955) into her own star vehicle, effectively relegating Richard Todd and Joan Collins to her supporting cast. Although magnificent as the ageing, rampaging and indomitable queen, Davis’s performance proved to be of limited interest to moviegoers in the mid-Fifties, now largely teenagers and early twenty-somethings. Marilyn Monroe proved far more appetising.

Since her small role in All About Eve in 1950, Monroe had triumphed in such films as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), River of No Return (1954), The Seven Year Itch (1955), The Prince and the Showgirl (1957) and Some Like it Hot (1959), making her Twentieth Century-Fox’s top actress and one of Hollywood’s most popular and profitable stars of the decade. By the mid-Fifties, she was the face, the embodiment and the voice of 1950’s Hollywood, whereas Bette Davis (once the incarnation of wartime women) struggled to maintain a place in the American film industry and found greater opportunities on television and stage.

Television certainly proved more lucrative for her in the Fifties, with many of the fans that had flocked to see her movies some ten years earlier watching her on the small screen in their homes in episodes of, among other things, Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1959) and Wagon Train (1959 and 1961).

To maintain her public profile, however, Davis returned to the theatre but her performances were often criticised as old-fashioned, poorly timed and in bad taste. For instance, when she acted on stage as Maxine Falk in Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana in 1961, her entrance brought the house down but the rest of the cast were unsettled by her attention-grabbing antics and the persistent screams and applause of her fans.

The publication of Bette Davis’s ghostwritten autobiography The Lonely Life in 1962 coincided with a major low point in her film career and can be seen as another attempt to maintain her public profile. Davis used this book to express her frustration with the current state of her life and career. Separated from Gary Merrill and struggling to find acting jobs, she depicted herself as a dedicated actor who had always wanted to produce distinguished work rather become a high-earning Hollywood star. She focused on her past fights with studio bosses and the constant difficulties of managing the conflicting demands of marriage and career. She also described her struggles to go on working in the 1950s as she grew older, making it clear that she remained desperate to work and was frustrated by her lack of opportunities as a 53-year old actress. What Davis didn’t know when she was working on her memoir was that a major comeback was just around the corner, thanks to none other than Joan Crawford.

What legends are made of

What happened next is the stuff of legend.

[See Shaun Considine’s book Bette and Joan: the Divine Feud (1989), the script of Anton Burge’s stage play Bette and Joan (2011) or Ryan Murphy’s an eight-part TV mini-series Feud (2017) for more details. Alternatively, read Davis’s own account in her late-life memoir This ‘N’ That (1988).]

According to Bette Davis’s own account, Joan Crawford arrived backstage during a performance of The Night of the Iguana in 1961 to give her a copy of a book called What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, suggesting that this would make a great film for the two of them. If Davis is right, Crawford wasn’t wrong. When the film was released with Crawford as Blanche and Davis as Jane Hudson, it caused a sensation. This black comedy and psychological thriller hybrid not only became the surprise hit of 1962 but it also earned Davis an Oscar nomination for her unflinching performance as Baby Jane Hudson, a demented elderly child star who persecutes her disabled sister. It is an astonishing performance, brave and audacious, in which Davis pulls out all the stops and leaves no holes barred. Although not an easy watch, it’s certainly a rewarding one, the likes of which had been rarely seen in Hollywood up until that point. It subsequently became a cult movie and proved to be one of Davis’s most durable and best-known films.

Bette Davis’s increased exposure in 1962 led to new ad campaigns and endorsements, TV appearances and other film projects. She was now back on top but in a very different kind of industry than the one she had flourished in some 20 years earlier. The big studios like Warner Bros. and Twentieth Century-Fox were being broken up and sold off and what was left concentrated on distributing independently made movies rather than actually making them. But Davis was prepared to work for all kinds of studio and take on all manner of roles, which ensured her survival.

Her first film after Baby Jane was shot in Italy and France. La Noia, or The Empty Canvas, was based on a novel by Alberto Moravia brought to the screen by writer-director Damiano Damiani for producer Carlo Ponti with Davis, Horst Buchholz and Catherine Spaak in the leading roles.

Another thriller followed. This was Dead Ringer (Paul Henreid, 1964), in which Davis played identical twin sisters; one good, one bad, just as she had done in her film A Stolen Life (Curtis Bernhardt) back in 1946. Davis subsequently starred in Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte (Robert Aldrich, 1963) playing an elderly version of her Jezebel character in a reworking of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Although the project began with Joan Crawford as her co-star, Olivia de Havilland stepped in as her replacement following a supreme clash of egos between the two divas. Davis’s next three films were all made in Britain, where film production was thriving and veteran Hollywood stars were in demand. Meanwhile, back in the States, TV continued to provide her with lucrative employment.

In 1966, Citadel Press published Gene Ringgold’s The Films of Bette Davis. Although a coffee table book, this provided an astute overview of the actress’ filmography with production details, synopses, images and reviews of all of her movies up to 1965. The tone was appreciative, celebrating her work. Film critic Henry Hart stated in a foreword that, “She succeeded at first by projecting an image which was the essence of personality, and has survived as a star because she was sufficiently intelligent and hard-working to learn the acting craft” (p.7). This publication suggested that Davis’s back catalogue was worth preserving and revisiting in 1966. Yet Davis was not about to be consigned to the history books and, even though it was becoming increasingly hard to secure film work, she ploughed on undaunted by bad scripts, decreasing budgets, poor working conditions and some inexperienced directors.

The Seventies proved to be a particularly lean period for Davis. The audience that had supported her throughout her career seldom went to the cinema during this decade and Hollywood was in the grip of a major recession, certainly at the start of the decade. In 1973, Davis began touring in her own one-woman show, Bette Davis in Person and on Film, and continued to do so until 1978. This consisted of a sequence of clips from the actress’ illustrious film career, mostly from the 1930s and ‘40s, followed by a live QnA session in which Davis responded to questions about her life and career from an interviewer, as well as from members of the audience. These shows attracted large audiences of gay men and established Davis as both a cult star and a queer one.

In 1974, Hawthorn Books published Mother Goddam by Whitney Stine. If gay men in their twenties and thirties wanted to find out more about Bette Davis, this was the perfect book for them. Not only because Stine provided a detailed account of Davis’s work, from her first screen test to an Italian movie called The Scientific Cardplayer (1972), but also because it featured a commentary in red type by Davis herself. Here, she clarified, elaborated upon and sometimes contradicted Stine’s account. This made it clear that she was a woman not to be messed about. Her strength, resilience and ‘attitude’ made her a perfect role model for an increasingly visible and assertive gay community.

By 1980, Bette Davis was well established as a gay icon, widely celebrated in the gay communities of New York, San Francisco and London. Her old movies were often shown in art-house movie theatres; most notably, Now, Voyager, All About Eve and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Consequently, she won new fans among successive generations of gays and lesbians around the world. She was frequently impersonated by drag queens in cabarets and gay bars, all of which consolidated her cult status.

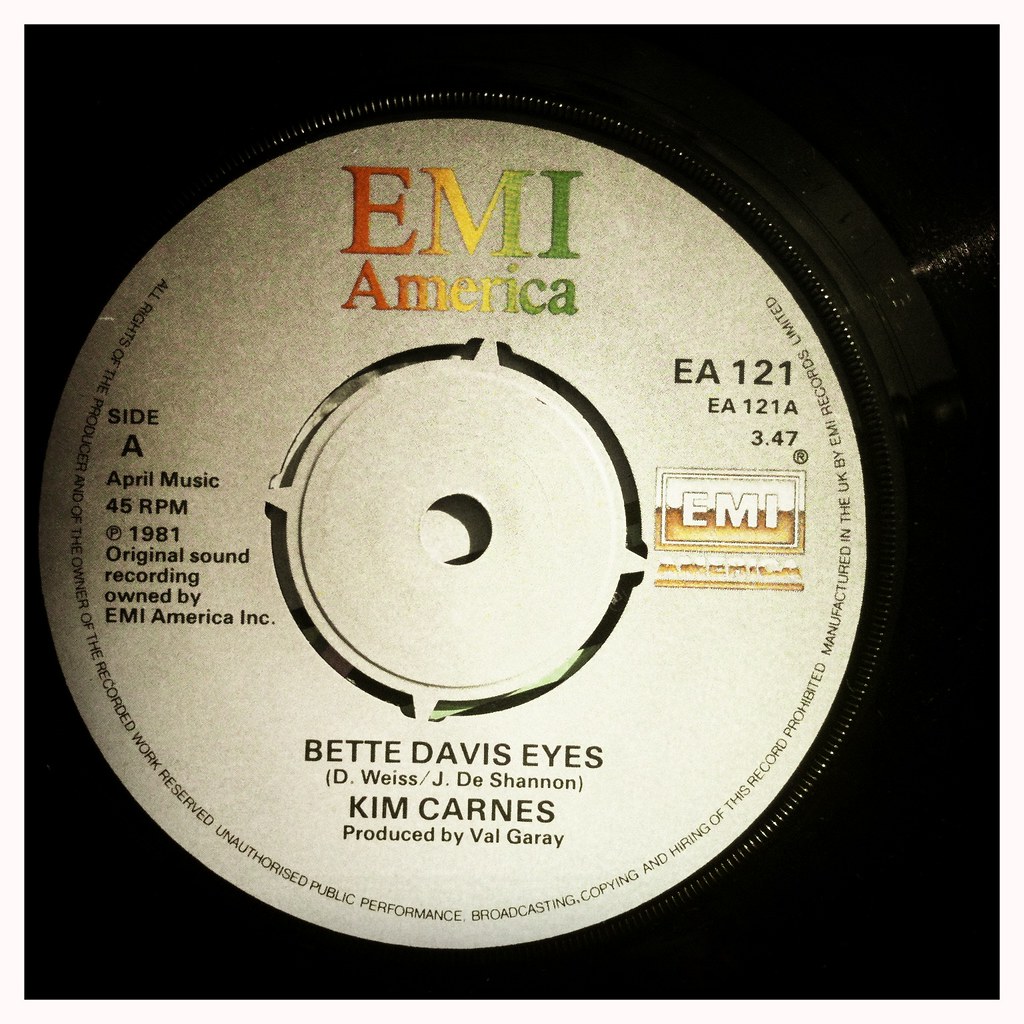

Davis also came to the attention of young people in 1981 when the singer Kim Carnes scored a number one hit with the song Bette Davis Eyes. This pop record spent nine weeks at the top of the Billboard charts and received a Grammy award. It also helped Davis to re-emerge in the early Eighties as a popular cultural icon with a strong brand identity.

Also in 1981, film critic and historian Charles Higham published Bette: A Biography of Bette Davis. This book proclaimed Davis to be a larger-than-life star, one who had been promoted, groomed and controlled by a Hollywood studio but one who, nevertheless, proved to be courageous and intelligent. Higham concentrated on her battles with the studio system to win some control over her own work so that it was a celebration of female empowerment and rebellion. He also spiced up Davis’s life story with feuds, scandal and furies. Her personal biography was then inter-woven with a critical assessment of her performances on screen, adding to her reputation as a great actor but also exposing more details of her private life to enhance her celebrity status. This decisively shifted the focus from Bette as actor/star to celebrity.

Yet Davis was still not content to rest on her laurels as a Hollywood legend or as a celebrity, finding a suitable outlet for her talent, persona and energy in a series of Made for TV movies in the early 1980s. Indeed, Davis did some remarkable work for television at this time, producing heartfelt and nuanced performances in social conscious-raising small-screen dramas, such as White Mama (Jackie Cooper, 1980), A Piano for Mrs Cimino (George Schaeffer, 1982) and Right of Way (Schaeffer, 1983). These all dealt with issues of ageing, including homelessness, loss of autonomy and suicide. They enabled Davis to extend her gallery of feisty, rebellious and unconventional women whilst advocating for better social care for the elderly. This small but remarkable body of work is well worth examining in terms of portrayals of old age. In contrast, her work for the cinema was largely undistinguished and is perhaps best forgotten.

Yet Davis was struck down by ill health in 1983. In that year, following an operation for breast cancer, she suffered a major stroke and then, some months later, broke her hip in fall. Afterwards, she became emaciated and it was clear that one side of her face could barely move and that walking was difficult and painful due to the hip that refused to mend. Despite inhibiting her ability to act on stage or screen, Davis was determined to go on working. By the mid-1980s, she performing again, in small (often cameo) roles, such as in the TV production of Murder with Mirrors (Dick Lowry, 1985), alongside Helen Hayes and John Mills, as well as in As Summers Die (Jean-Claude Tramont, 1986) with Jamie Lee Curtis.

However, Davis was struck by a further body blow in 1985 when her daughter published a scurrilous biography called ‘My Mother’s Keeper.’ Here, B.D. Hyman detailed her mother’s failings as wife and mother, with numerous examples of her controlling and selfish behavior, her addiction to work and alcohol, her violent temper, irrational rages and cruel jokes. To make the bestseller lists, the book exposed the most private and sordid aspects of Davis’s personal life. As an exposé, it was salacious, sensational and exaggerated despite being advertised as ‘understanding’ and ‘honest.’ Little regard was given to the effects that it might have on Davis’s now precarious health, career and image. In fact, it couldn’t have been better calculated to jeopardize her recovery and destroy what remained of her career and public persona. Yet, once again, Davis revealed a remarkable resilience and, rather than withdraw from public view, she took whatever work was available to her, often in the full glare of the celebrity spotlight.

TV chat shows became the mainstay of Davis’s work in the late 1980s. Here, she reproduced her anecdotes, often while smoking heavily. Despite being largely concealed behind veils, hats and gloves, her physical frailty was apparent and her speech was noticeably slurred. Yet her wit, intelligence and fighting spirit still came through loud and clear. What was also clear was that interviewers admired her and audiences loved her.

In 1987, Davis completed work on one of her most remarkable films, appearing alongside fellow screen legends Lillian Gish and Vincent Price. This was Lindsay Anderson’s The Whales of August (1987), a small, intimate and tender film about two elderly sisters spending their last summer together at their holiday home on the Maine coastline. Here, Davis played one of her toughest roles as the cranky blind older sister Libby. This touching portrait of a woman close to death would have made a fitting end to Davis’s illustrious film career.

Yet Davis still no intention of quitting and therefore accepted a starring role in Larry Cohen’s black comedy Wicked Stepmother playing a modern-day witch who marries a wealthy widower, to the horror of the old man’s family. Davis lasted two weeks on set before having to withdraw for health reasons. The project was subsequently completed with another actress in the Davis role and it went straight to video.

[For more on this film, see my essay ‘Bette Davis: Acting and Not Acting her Age’ in Women, Celebrity and Cultures of Ageing: Freeze Frame, (eds.) Deborah Jermyn and Su Holmes (Palgrave 2015), pp. 43-58. This chapter can be accessed and downloaded online from here https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137495129_4]

In 1988, with help from her personal assistant Kathryn Sermak and writer Michael Herskowitz, Davis produced a second memoir entitled This ‘N’ That and then hit the road to publicise it on TV chat shows around the world. In October 1989, she fell ill in Spain while attending a film festival and died soon after in a Paris hospital. She was 81 years of age.

After Davis

Shaun Considine’s Bette and Joan: the Divine Feud was published shortly after Davis’s death, which focuses on (and embellishes) the bitter rivalry of two great screen divas Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. Interestingly, it was published by Sphere Books, the same company responsible for the scurrilous My Mother’s Keeper. It quickly became a bestseller and something of a gay Bible. Once again, truth wasn’t allowed to get in the way of a good story. And what a story it was! The Bette Davis script was now taking shape, creating a character far more interesting and complex than anything Davis had played on screen throughout her long career.

A flurry of biographies appeared thereafter, revealing the intimate details of her remarkable and passionate life, books like Lawrence J. Quirk’s Fasten Your Seatbelts: The Passionate Life of Bette Davis (1990). In most cases, her screen performances were analyzed and evaluated but, more often, her personality was laid bare and even subjected to psychological analysis. Davis’s work, life and personality were further explored in biographies published in the first decade of the 21stcentury, alongside continuing scrutiny and assessment of her screen performances; notably, Ed Sikov’s Dark Victory: The life of Bette Davis (2007). Yet, the most intimately observed account of Davis’s later years was published in 2017, written by her former personal assistant Kathryn Sermak, who Davis looked upon as a daughter after her rift with B.D. Hyman. In Miss D & Me, there’s little mention of Davis’s films and performances, the attention remaining squarely focused on personal details, producing a vivid picture of the actress’ life as a celebrity, including detailed accounts of how she prepared for various public appearances. Encounters with the public mark some of the high points of this narrative, such as on a road trip through France in August 1985.

Since her death, Bette Davis has been memorialized and immortalized. A season of her best 30 films was screened in London at the National Film Theatre in August 2006. Two years later, the London Gay and Lesbian Film Festival marked the centenary of her birth with a special presentation on the lasting impact of her films. In 2009, a documentary was released in cinemas called Queer Icon: The Cult of Bette Davis, having its world premiere at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco. Two years later, a play by Anton Burge was staged in London’s West End called Bette and Joan, depicting the epic battle on the set of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? It played to packed houses before going on tour and was also broadcast on BBC Radio 4. In January 2015, Bette & Joan: The Final Curtain was staged at the St. James Theatre in London. This play was devised and performed by Sarah Thom and Sarah Goodman with a script by James Greaves. More high profile was Susan Sarandon’s performance of Bette Davis opposite Jessica Lange’s Joan Crawford in Feud (2017), an eight-part TV mini-series produced by Ryan Murphy for Fox TV. All of these productions, however, suggest an enduring public fascination with these two Hollywood stars of the studio era, even though it depicts them largely as monsters that were more profane than sacred.

In recent years, Davis and her films have shown no sign of being forgotten. One example being a two-day academic conference in October 2018 entitled All About Bette: The Cultural Legacies of Bette Davis at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, in the USA, where Kathryn Sermak and I gave keynote presentations in addition to a raft of really great papers and a video essay. To this day, Bette Davis is remembered as a great actor, a fighter, an independent spirit, as a Hollywood diva and a gay icon. This is partly because she was a huge star and a remarkable actor but also because she maintained her celebrity profile during the troughs of her film career. Although she earned a place in film history during her lifetime, she stubbornly refused to be consigned to the history books and repeatedly insisted on maintaining her cultural visibility by whatever means she could.

Davis’s long and distinguished career demonstrates many of the classic hallmarks of film stardom: the rise to success and the fall from glory; the peaks and the troughs; the adjustments to accommodate age and changes in the nature of the film industry. Consequently, she has played a key role in the development of Star Studies as an academic discipline. Notably, she features prominently in Richard Dyer’s Stars (1979), Jackie Stacey’s Star Gazing (1994), Paul McDonald’s The Star System (2000) and my own Star Studies: A Critical Guide (2012).

Davis’s career in the 1930s and ‘40s, for instance, illustrates the restrictions of the contract system in studio-era Hollywood, while her career after 1945 is delineates the consequences of the break-up of the studio system and the shift undertaken by stars as they were transformed from studio-owned and controlled properties to freelance agents responsible for their own choices and publicity. Her career after 1960, meanwhile, provides a case study for how studio stars survived in the post-studio era by becoming cult stars, appealing predominantly to marginalized audiences, while continuing to move between mainstream and more marginal productions. Meanwhile, her posthumous career is instructive in terms of how and why some stars are remembered while others are forgotten.

At this moment in time, almost thirty years after her death, it looks very unlikely that Bette Davis will ever be forgotten. For there is so much to remember and admire about this little Bostonian who not only fulfilled her girlish dreams of becoming an actress on the Broadway stage but subsequently became one of Hollywood’s greatest screen performers and one of America’s most respected celebrities. It can certainly be claimed that she is one of the most fascinating and accomplished women to have lived and worked on this planet. In short, her’s is great story that deserves to be told and told again. As I’m sure it will.

There is more on Bette Davis’s work at Warner Bros. in the 1930s in the section devoted to my book When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-29 (2018) on my website.

Be the first to write a comment.