Let me introduce myself. My name is Martin Shingler … and it’s quite possible that I’m addicted to the Hollywood movie star Bette Davis (1908-89). I’ve certainly spent the greater part of my academic career talking and writing about her, as a film star and as a screen performer. Indeed, the first thing I ever published was on Bette Davis, an article in the journal Screen called ‘Masquerade or Drag? Bette Davis and the Ambiguities of Gender’ (1995).

[My ‘Masquerade or Drag?’ article in Screen can be accessed online here https://academic.oup.com/screen/article-abstract/36/3/179/1627916]

The second thing I published was on Davis as well, an article called ‘The Fourth Warner Brother and her Role in the War’ in the Journal of American Studies (1996). After that, I just kept on going. Between 2006 and 2008, I just couldn’t stop myself. I did try in 2009 but it didn’t last long. When asked to write about a brief moment of a film, before I knew what I was doing, I’d produced a detailed analysis of Bette Davis’ star entrance in Jezebel for James Walters and Tom Brown’s wonderful anthology Film Moments (2010). And after that, well, I never looked back. More Davis essays followed, thick and fast. And it wasn’t just essays either. Bette consistently made her way into my books, notably Star Studies: A Critical Guide (2012) and When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018). She’s even on the cover of the latter.

My article ‘The Fourth Warner Brother and her Role in the War’ in the Journal of American Studies (1996) can be accessed here https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-american-studies/article/abs/fourth-warner-brother-and-her-role-in-the-war/C762896120422D72221305B3685AA562.

Not surprisingly, people think I’m obsessed with Bette Davis. I don’t think I am. For me, she’s just the well that never runs dry and the gift that keeps on giving. If I want to write about gender ambiguity, she’s perfect. When I’m writing about the role of women in Hollywood, who could be better? She also makes for a great study of melodrama, or audiences and fans, or stardom, or ageing or screen acting, or the links between Broadway and Hollywood. But then, she is always on my mind. And I guess my mind isn’t very far from my heart.

[For more on Mr Skeffington, see my essay ‘Bette Davis: Acting and Not Acting her Age’ (2015), which can be accessed online here https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137495129_4]

Well, perhaps I am obsessed! And maybe that obsession disqualifies me from being able to write about Bette dispassionately … objectively … academically. Perhaps, but so far I seem to have been able to get away with it. And, hopefully, I can keep on getting away with it … because I’m not done yet. There’s still more to explore. For instance, until now I’ve not really explored Bette’s celebrity in any great detail.

To find out more about Bette Davis, return to the dashboard and click on the image of Bette Davis with her co-star and soon-to-be husband Gary Merrill in All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950).

Other interests

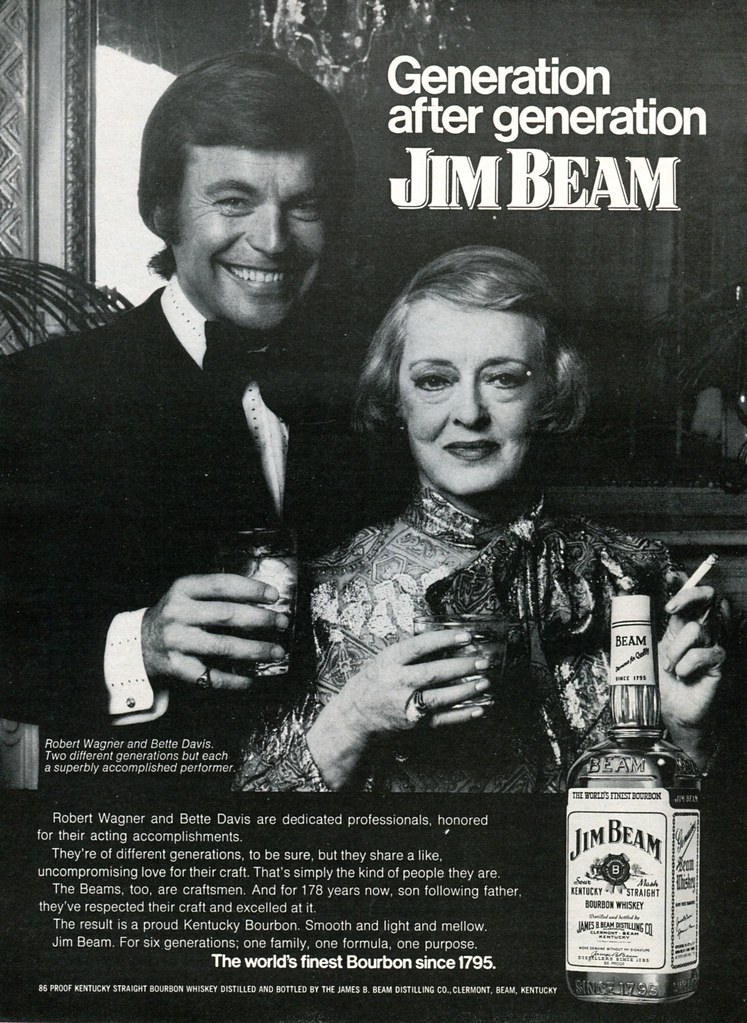

I chose the image above of Bette Davis as Julie Marsden in Jezebel (Wm. Wyler, 1938) as the cover of When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018) to indicate that she features prominently in the book. And indeed she does. She makes a sudden appearance halfway through chapter 5, where I describe her entrance in George Arliss’ film The Man Who Played God (John G. Adolfi, 1932). She remains thereafter in all the succeeding chapters, making small appearances in chapter 6 on Gold Diggers of 1933 (Melvyn LeRoy, 1933) and Lilly Turner (Wm. Wellman, 1933) and chapter 7 on The Petrified Forest (Archie Mayo, 1936), although she really comes in to her own in chapter 8, which is devoted to the films she made at Warner Bros. from 1937 to the end of 1939, notably The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Michael Curtiz, 1939). Yet, while Bette plays a leading role in my book, there are other stars that caught my eye and ear which are featured here, stars that have become a source of fascination and great pleasure; notably, Miss Ruth Chatterton.

It was Bette Davis who introduced me to Ruth Chatterton. When I eventually got round to watching Bette in her second Warner Bros. picture (well, officially a First National production), it was the film’s star that caught my ear. In The Rich Are Always with Us (Alfred E. Green, 1932), Chatterton plays Caroline Grannard, the richest woman in the world who, despite her great wealth, is unhappy since she is torn between her feckless husband Greg (John Miljan) and her young lover Julian Tierney (George Brent). This love triangle is further complicated by the fact that Caroline’s best friend Malbro (Bette Davis) is suffering the pains of unrequited love for Tierney. While the plot is gossamer thin, the characters are finely drawn and enchanting, amusing and sympathetic, and their dialogue fizzles with excitement, tension and humorous banter. Meanwhile, the whole thing sizzles with an undercurrent of sexual energy, which may in part have resulted from the fact that the star had fallen in love with her leading man and, shortly after work completed on the film, George Brent became Mr. Ruth Chatterton.

It was, as I say, Chatterton that caught my ear with a wonderfully rich voice, and an impressive vocal dexterity, as well as a giggle that humanised an otherwise sophisticated and elegant persona. Exuding charm and intelligence, she took the spotlight (beautifully crafted by cinematographer Ernest Haller) with a commanding performance that dominated the screen and the soundtrack. Her vocal tones seemed old-fashioned, imperious and even arch, yet a natural charisma softened an all-too-obviously polished image, rendering her sympathetic and relatable. I connected. Intrigued, I sought out other Chatterton films and began investigating her backstory.

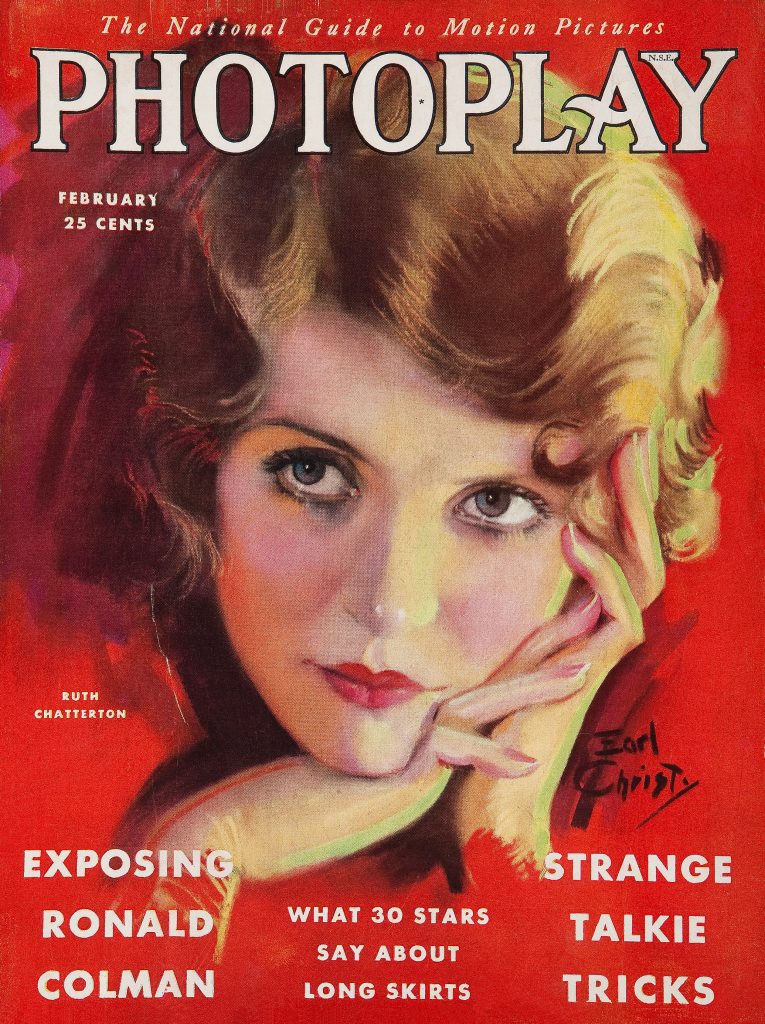

The first lady of the screen

Before she became an aviator and a novelist, Ruth Chatterton (1892-1961) was a star of stage and screen. She was in her mid-30s when she began her Hollywood career, an age significantly above the average for female film stars, which was generally between 20 and 25 during the 1920s. However, by the time she made her film debut, Chatterton was already a big star, having attained stardom on Broadway at the age of 22 and, thereafter, honed her acting skills under the tutelage of Henry Miller (1859-1926), the English-born American actor-director-writer-producer-manager. Her acting career began in 1906 when, after completing her formal education at the exclusive Pelham School for Girls, she joined the Washington Stock Company and acted alongside Helen Hayes, Lowell Sherman and Pauline Lord. In October 1911, she made her Broadway debut in the supporting cast of James Clarence Harvey’s The Great Name at the Lyric Theatre on 42ndStreet, graduating to her first leading role on Broadway in 1912 in A. E. Thomas’ The Rainbow, starring Henry Miller at the Liberty Theatre, which ran for over 100 performances from 11 March. Her first major hit, however, came in 1914 when she starred as Judy in Jean Webster’s hugely successful Daddy Long Legs at the Gaiety Theatre. This ran for 264 performances from September 1914 to May 1915, transforming Chatterton into a Broadway star.

Another major Chatterton hit was A. E. Thomas’s Come Out of the Kitchen, which ran at George M. Cohen’s Theatre for 224 performances in 1916 and 1917. In 1919, Henry Miller’s production of George Scarborough’s comedy Moonlight and Honeysuckle, at his theatre on 43rdStreet in New York City, also starred Ruth Chatterton with Sydney Booth and Lucile Watson.

In 1924 she appeared in Henry Miller’s production of the musical comedy The Magnolia Lady by A.E. Thomas and Alice Duer Miller with music by Harold Levy and songs by Anne Caldewell.

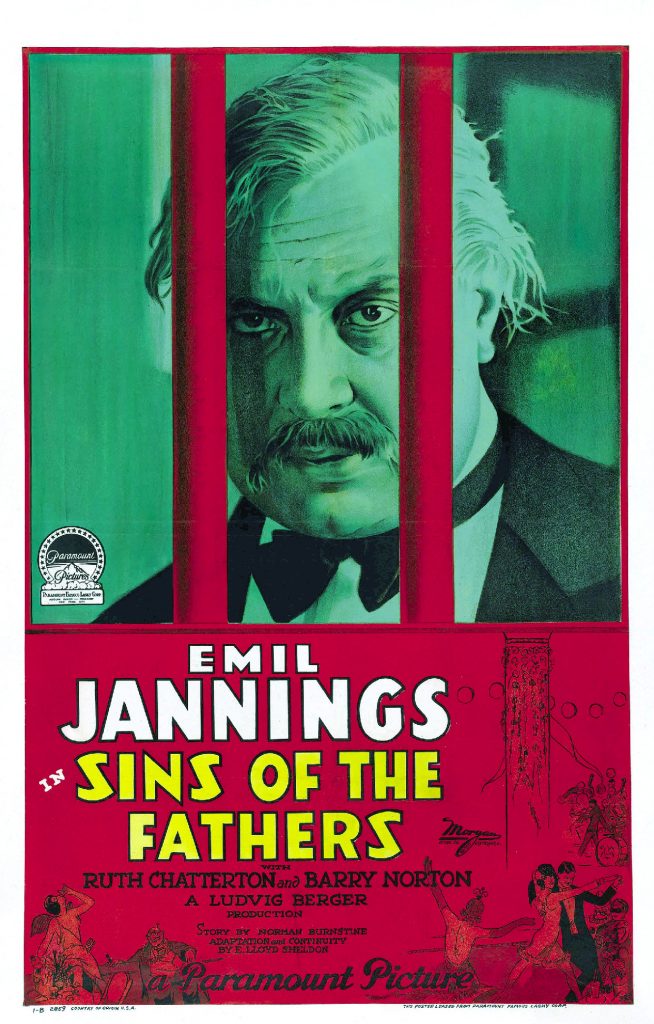

Other Broadway hits included leading roles in J.M. Barrie’s Mary Rose (1921) and The Little Minister (1925), during which time she resisted the allurements of Hollywood. However, in 1928 she succumbed when invited to perform opposite the great German star of stage and screen Emil Jannings at Paramount in his silent film Sins of the Fathers (dir. Ludwig Berger).

Chatterton remained at Paramount to star in a series of talking pictures and quickly became its top female. She was Oscar nominated for her performances in the maternal melodramas Madame X (Lionel Barrymore, 1929) and Sarah and Son (Dorothy Arzner, 1930) as self-sacrificing mothers condemned as disreputable yet adored and admired by audiences.

Other hits at Paramount included Anybody’s Woman (Dorothy Arzner, 1930) with Clive Brook, Unfaithful (John Cromwell, 1931) with Paul Lukas, and Once a Lady (Guthrie McClintic, 1931) with Ivor Novello, in the type of ‘sophisticated’ drama that would be banned by the Production Code from 1934.

A voice at Warners

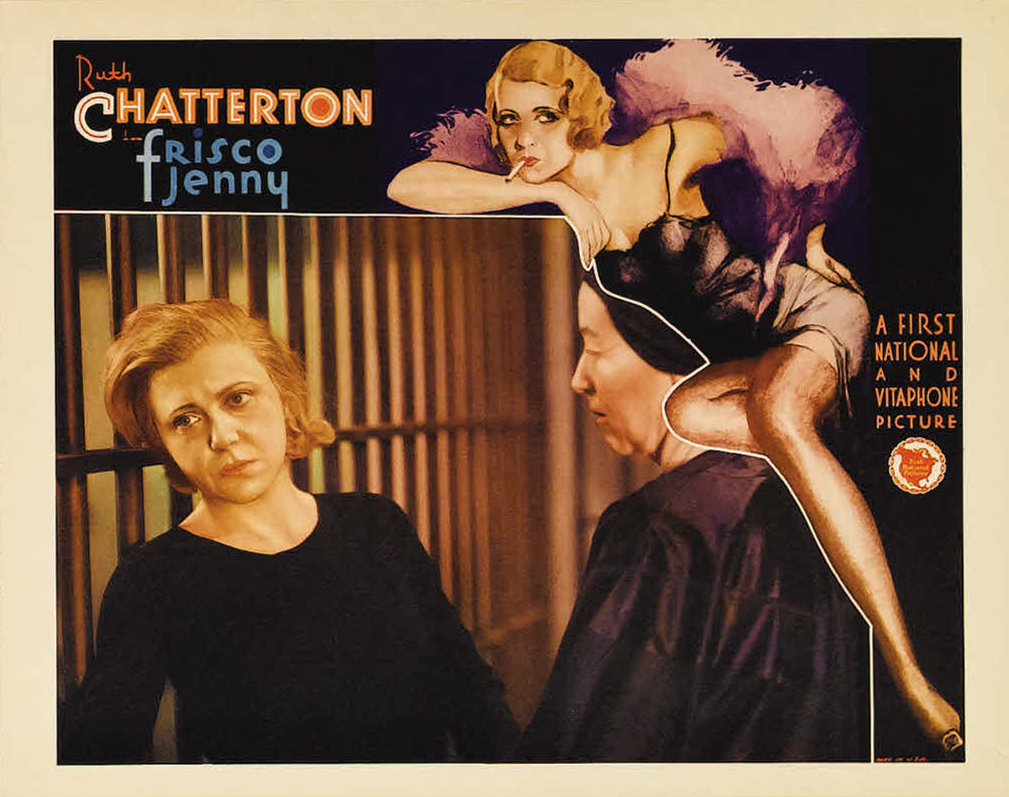

Warner Bros. poached Chatterton from Paramount in January 1932 with a starting salary of $8000 a week. She remained at the studio for the next two years, making a total of six films for their subsidiary company First National. These were The Rich Are Always with Us (Alfred E. Green, 1932), The Crash (William Dieterle, 1932), Frisco Jenny (William Wellman, 1932), Lilly Turner (William Wellman, 1933), Female (Michael Curtiz, 1933) and Journal of a Crime (William Keighley, 1934). Unfortunately, none of these received Academy awards, nominations or rave reviews, and the most successful only generated modest profits. Within a relatively short space of time, the studio’s commitment to the development of the Ruth Chatterton film cycle waned in favour of younger female stars such as Kay Francis, Joan Blondell, Bette Davis, Ruby Keeler and Olivia de Havilland. Yet the work she produced under contract to Warners at the very height of the Depression is pretty remarkable by anyone’s standards.

Take, for instance, The Rich Are Always With Us with its smart characters, ultra modern sophisticates with advanced notions of sex and marriage. Stylish and upmarket, the film revels in smart talk. Witty aphorisms come and go in quick succession, leaving the audience as breathless as the actors. The cast is required to deliver banter in clear and well-articulated voices that evoke their high-class status, intelligence, youth and modernity. Their vivacious repartee creates a constant patter as the characters involve themselves in a complex and sometimes vicious social game. Once in a while something heartfelt, genuine and revelatory slips through, revealing true emotion, the humanity and vulnerability of the character that renders them sympathetic. Such transitions demanded considerable virtuosity on the part of the actors, including range, insight and dexterity.

[For more on The Rich Are Always with Us, see my essay ‘Rich Voices in Talky Talkies: The Rich Are Always with Us (1932)’ in The Soundtrack (vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 109-115).]

In stark contrast was Frisco Jenny (Wellman, 1932), a maternal melodrama akin to Madame X and Sarah and Son but much tougher, more sordid and tragic, with its grim depiction of the criminal underworld, the legal system and motherhood. Here, Chatterton plays Jenny Sandoval, the daughter of a notorious and brutal San Franciscan saloonkeeper. She is in love with an impoverished piano-player, who is killed, along with Jenny’s father, in the 1906 earthquake. Afterwards, an unmarried Jenny gives birth to a son, who she attempts to bring up whilst working as a call-girl. When the authorities attempt to remove the child, deeming her to be an unfit mother, Jenny places her son with a wealthy upper-class couple who eventually adopt him as their own. Jenny’s son grows up to become a celebrated sportsman and, after graduating from university, becomes an attorney and eventually the District Attorney. Meanwhile, Jenny has formed a professional partnership with Steve Dutton (Louis Calhern) and together they run a successful crime syndicate specializing in prostitution, gambling and bootleg liquor. When the District Attorney (Jenny’s son) sets out to destroy their criminal organisation, Dutton threatens to inform him about his true parentage. To prevent this, Jenny shoots Dutton outside the D.A.’s office and is subsequently tried and found guilty of murder. Awaiting execution on Death Row, Jenny is visited by her off-spring (the D.A.) who begs her to reveal the reason behind the murder. However, she maintains her silence, refusing to reveal the truth, and finally takes the knowledge that she is his mother to the grave.

Despite all her efforts and best intentions, Jenny’s personal sacrifices consistently go unrecognised and unrewarded. Indeed, the film ends not only with her death but also with the destruction of her scrapbook of clippings about her son, painstakingly collected over many years. Finally,, everything that Jenny has worked for is stripped away, leaving her broken and alone. Her consolation is that she is able to kiss her son’s hand during his visit to her prison cell shortly before her execution; that and the security of knowing that her son’s good life will not be ruined by his association with her. But this all seemed too grim and hopeless at the very height of the Depression. Far more popular was 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) starring Chatterton’s husband George Brent alongside Ruby Keeler, Warner Baxter, Bebe Daniels, Ned Sparks, Ginger Rogers, Dick Powell and a bevy of leggy showgirls who were put through their paces by choreographer Busby Berkeley.

In 1933, Chatterton made a truly remarkable movie with husband George Brent as her co-star. Female was directed by Michael Curtiz and featured Chatterton in the role of a female Lothario, the owner-manager of an automobile factory who considers it a perk of her job to be able to sleep with any of the good-looking young men working for her company, until she finally meets the man of her dreams (George Brent). Until then, she is tough, sophisticated, hard-working, fast-living, hard-drinking, pampered, financially independent and her own woman, despite being more like a man in the seduction stakes. It was a film that turned conventional sex roles on their head, at least until the closing moments of the movie when the normal order of things was (unconvincingly) restored and all the fun drained out of the film. Unfortunately though, this was just too unconventional to have widespread appeal, particularly at a time when so many American men felt emasculated due to high levels of unemployment. Chatterton, it seems, was making really interesting and original movies but these just happened to be all wrong for the times.

After Warners

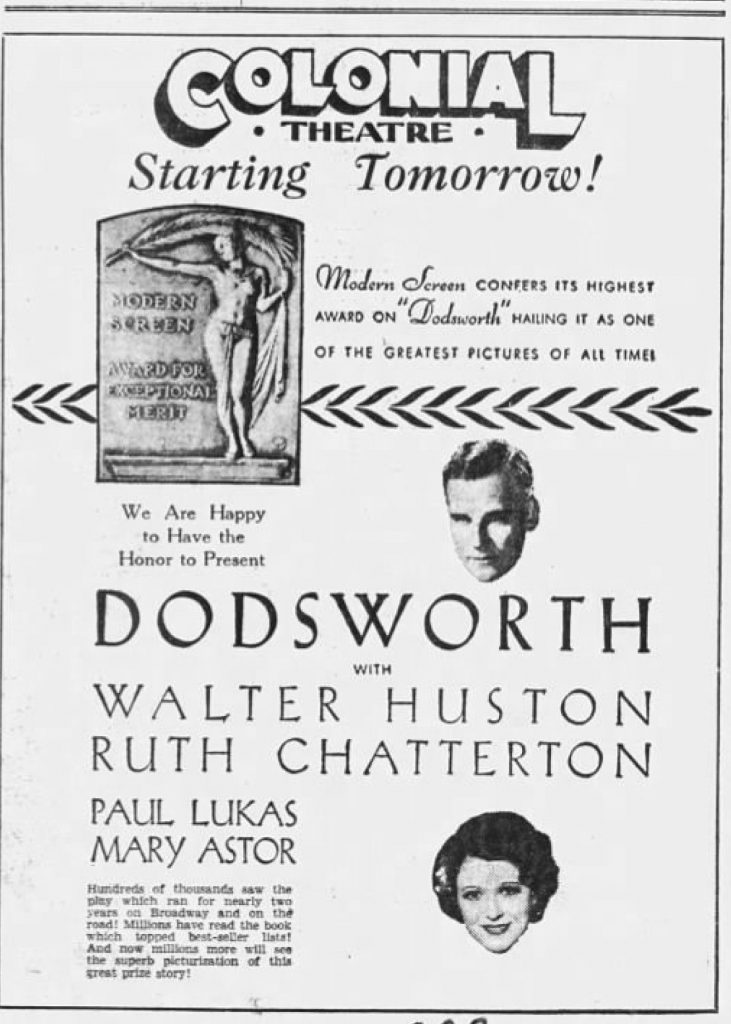

Chatterton’s time at Warners coincided with a marked decline in her popularity and star power. Yet her film career was far from over. After leaving the company in 1934, she appeared in several major Hollywood pictures, most notably Dodsworth (Wm. Wyler, 1936), in which she co-starred with Walter Huston as her long-suffering and estranged husband, ably supported by an impressive cast that included Mary Astor, Paul Lukas, David Niven and Maria Ouspenskaya. This was a strong ensemble and a quality production, made for Goldwyn Studios. Well received by both critics and audiences, it went a long way towards restoring Chatterton’s reputation after the disappointment of her Warner years.

By 1940, Chatterton had retired from acting, withdrawing to Connecticut to breed French poodles, fly airplanes and write novels, including Homeward Borne (1950) and The Betrayers (1953). During the Fifties, however, she was lured out of retirement to perform on television and on stage. Imagine my delight one day while working at the New York Library for the Performing Arts when I came across a copy of The Playgoer featuring Ruth Chatterton on the cover (see below). Even more delightful was the discovery that she’d played the leading role in John van Druten’s play Old Acquaintance (1940) at the Myrtle Beach Playhouse in South Carolina in 1955. Here, Chatterton performed the role of novelist Kit Marlowe, a part originated on Broadway by Jane Cowl in 1940 and realised for the big screen by Bette Davis in 1943. It’s wonderful to imagine what she did with this role, particularly when her character finally loses patience with her best friend Millie and, taking her by the shoulders, gives her a good shake.

The following year she played Regina Giddens in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes at the Fred Miller Theatre. This was a part performed originally on Broadway by Tallulah Bankhead in 1939 and on screen by Bette Davis in 1941. It was a complex and unsympathetic role, a woman of charm and sophistication, powerful and ambitious, duplicitous and ruthless with a strong independent and wilful spirit that leads ultimately to her own destruction as well as those around her. It was a part that would clearly have enabled Chatterton to draw not only on her skills as a performer but also her intelligent, commanding and charming persona. It suggests that the actress still relished the challenge of playing unconventional and multi-dimensional roles at the age of 64.

[For more on Ruth Chatterton, see Chapter 6 of my book When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018), notably pages 140-150.]

A face of the Twenties

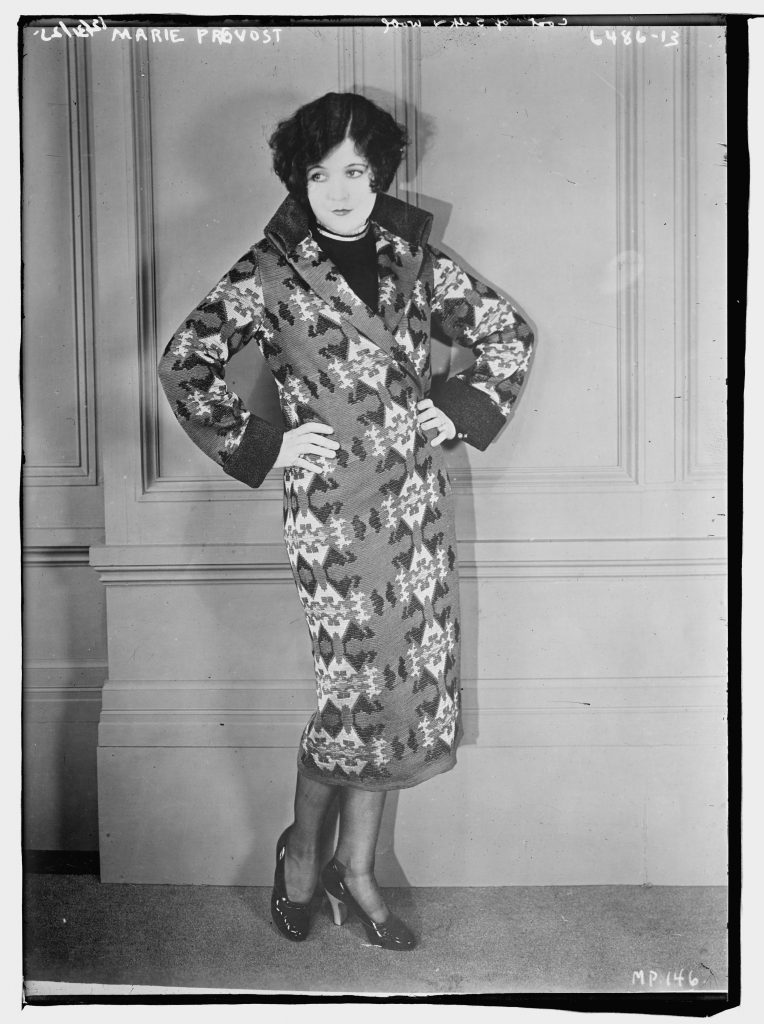

If Ruth Chatterton was one of the great voices of the late 1920s, Marie Prevost was one of Hollywood’s great faces, a star whose acting career was largely destroyed by the arrival of ‘talking pictures.’

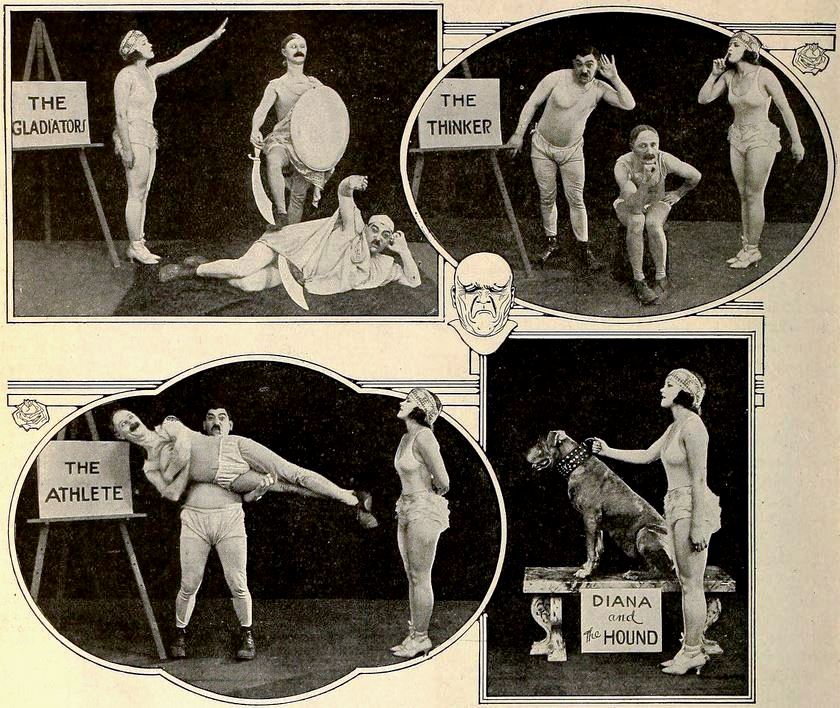

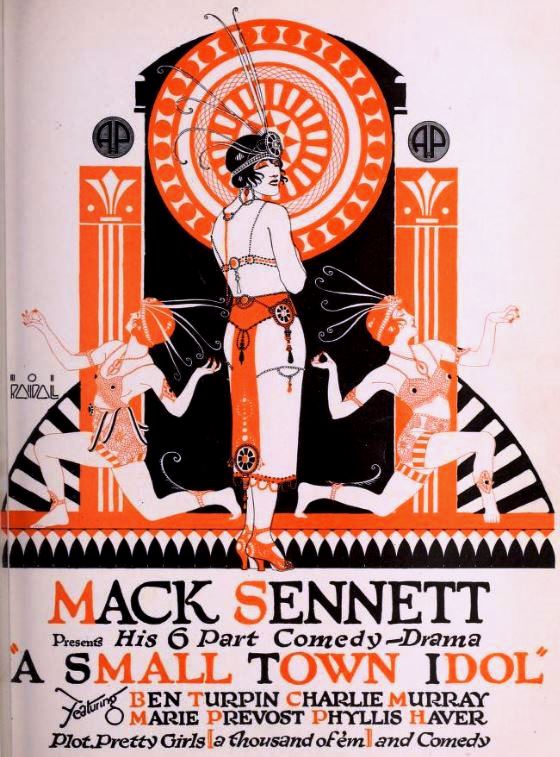

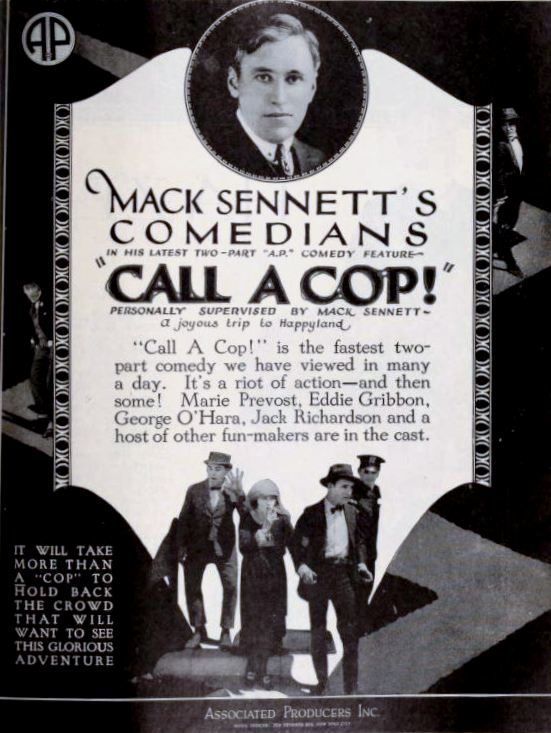

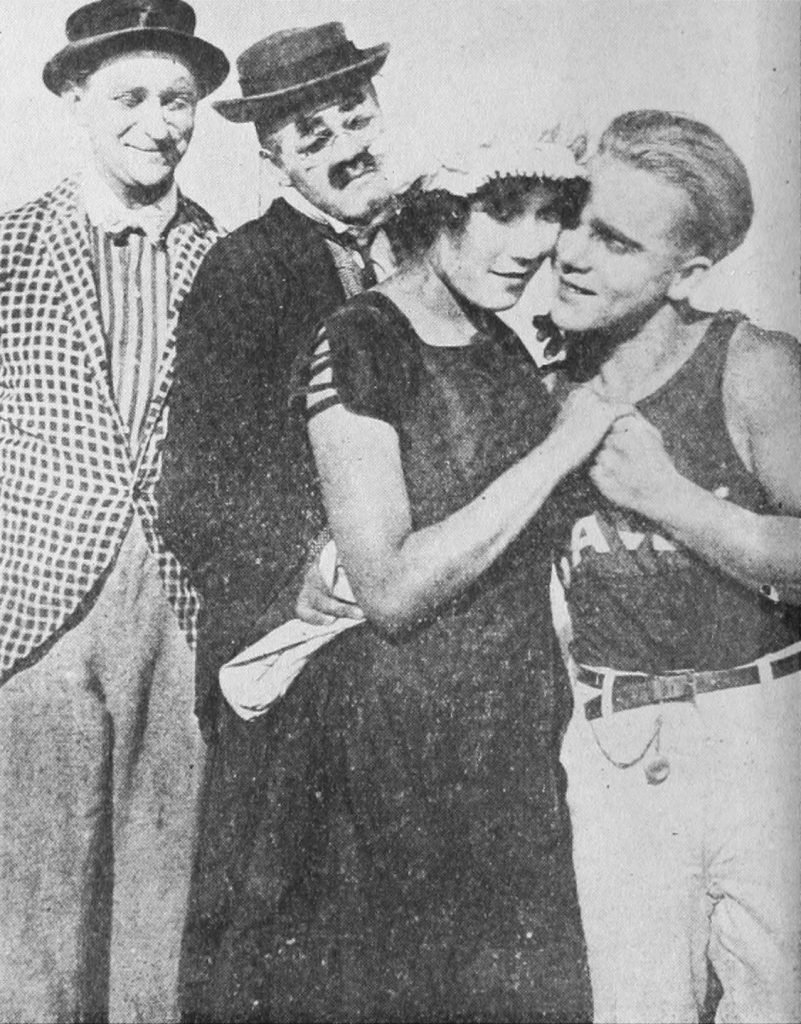

In the mid-1910s, Prevost secured a place in Hollywood on account of her body rather than her face. After joining Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studio in 1915, she made no less than thirty movies over the next four years, appearing in such fare as Secrets of a Beauty Parlor (Harry Williams, 1917), Those Athletic Girls (Edward F. Cline and Hampton Del Ruth, 1918), Her Screen Idol (Edward F. Cline, 1918) and The Village Chestnut (Raymond Griffith and Water Wright, 1918). In 1919, she co-starred with cross-eyed comedian Ben Turpin in When Love is Blind (Edward F. Cline , 1919) and Uncle Tom Without a Cabin (Edward F. Cline and Ray Hunt, 1919).

Prevost was a leading member of Sennent’s stock company of players by 1921, one of a number of ‘pretty girls,’ yet she was also emerging as a distinct comic talent at this time, having honed her silent screen performance skills in a wide array of short films, such as A Small Town Idol (Kenton & Sennett, 1921).

More than a pretty face

Sennett’s ‘pretty girls’ had it tough. They not only had to be good looking, healthy and fit but needed to endure the rampant sexism of the American film industry, the lechery of male co-workers and employers, in addition to a relentless factory-based system of formulaic film production designed to satisfy the relatively unsophisticated tastes of moviegoers in the Teens as well as their insatiable hunger for more product, similar to yet different from the films they’d previously enjoyed. Moviegoers and movie moguls wanted more, more, more from its screen performers and only a very few stars at this time (mostly those with Broadway credentials) could demand restrictions on their workload in addition to high salaries and a range of other perks. Keystone, which featured some of the most popular and talented stars of the early silent film era, was not the place where stars could luxuriate and exercise creative control over their work, which is why so many (Charlie Chaplin, Mabel Normand and even Marie Prevost) moved on.

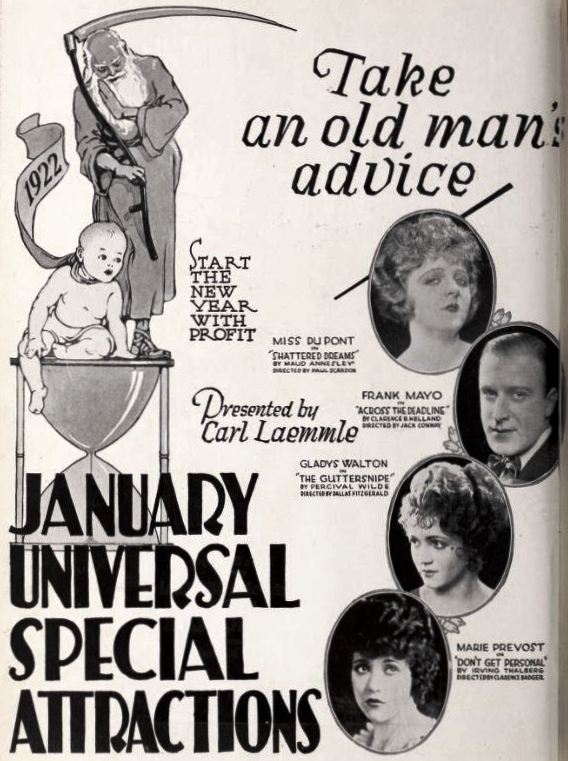

Prevost made her last Keystone film in the spring of 1921 and then joined Universal, which promised her more consistent star billing above the title of her films but also better roles in feature films with higher budgets and production values. It was as though she was graduating from the factory floor to an office job. It was a chance to not only earn more money but to create more three-dimensional and individuated characters than stock types.

Under King Baggott’s direction

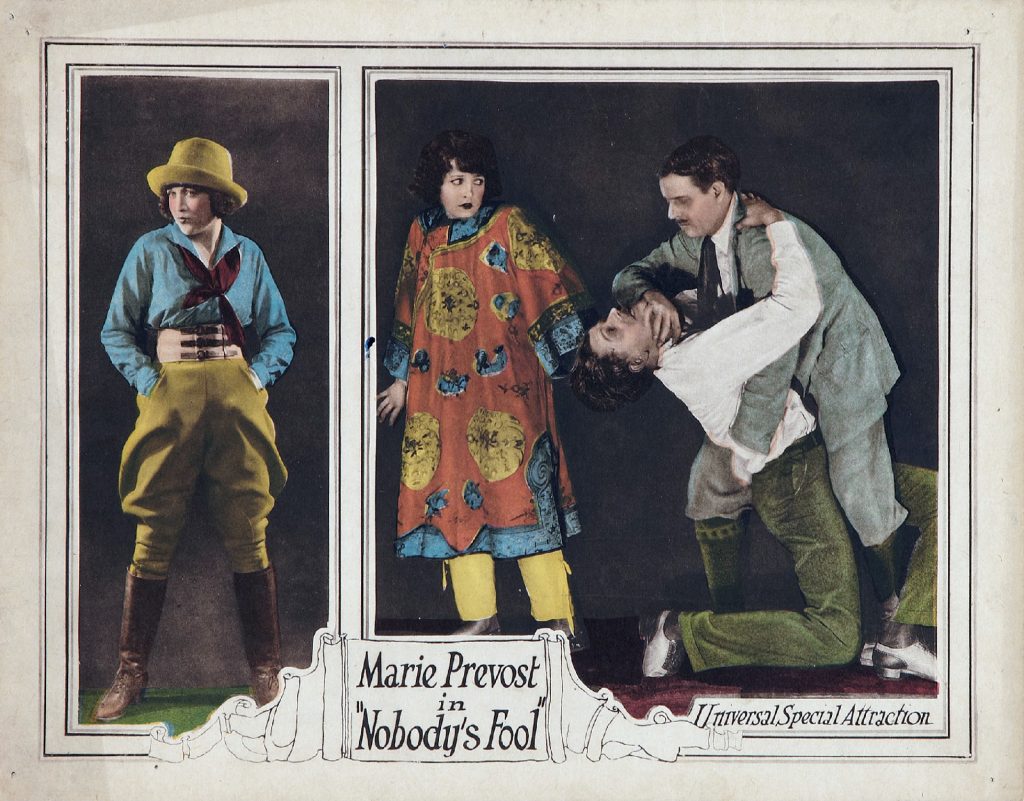

Prevost specialised in comedy at Universal. Yet there was much more to her work here than come hither looks, pratfalls and other slapstick antics. As the lobby card below suggests, melodramatic posturing and more dramatic and heartfelt emotional gesturing and expressions were also required of her in films such as Moonlight Follies (1921), Nobody’s Fool (1921) and Kissed, in which she was directed by King Baggott. As an actor with stage and screen experience, Baggott had much to teach Prevost about film acting while directing her on these three movies, lessons that were much needed given her background in modelling and her on-the-job training at Keystone, which consisted largely of improvising scenes as a stock type. She clearly needed help in devising more psychologically nuanced characters in a wider range of emotional states.

Interestingly, the above item of promotional material for Nobody’s Fool presented Prevost as both a modern, active and independent heroine (see image on the left) and a traditional ‘damsel in distress’ (image on the right), suggesting a complex and multi-dimensional persona likely to appeal to different kinds of moviegoer in the early Twenties. It is certainly an invitation to read Prevost as more than a simple device to elicit laughs or supply the film’s erotic spectacle but rather to provide narrative development in which her character Polly Gordon undergoes some kind of psychological, ontological or emotional transformation. Yet, as a still from the film Kissed suggests, Prevost was still required to provide moments of erotically-charged spectacle as the star of her Universal pictures, even if occasionally she was able to assume a dominant role in romantic coupling, as this image illustrates.

After making the silent farce The Married Flapper (dir. Stuart Paton), co-starring with Kenneth Harlan as her on-screen husband, Prevost left Universal to become a leading member of Warner Bros. stock company of actors.

Warners’ resident Flapper

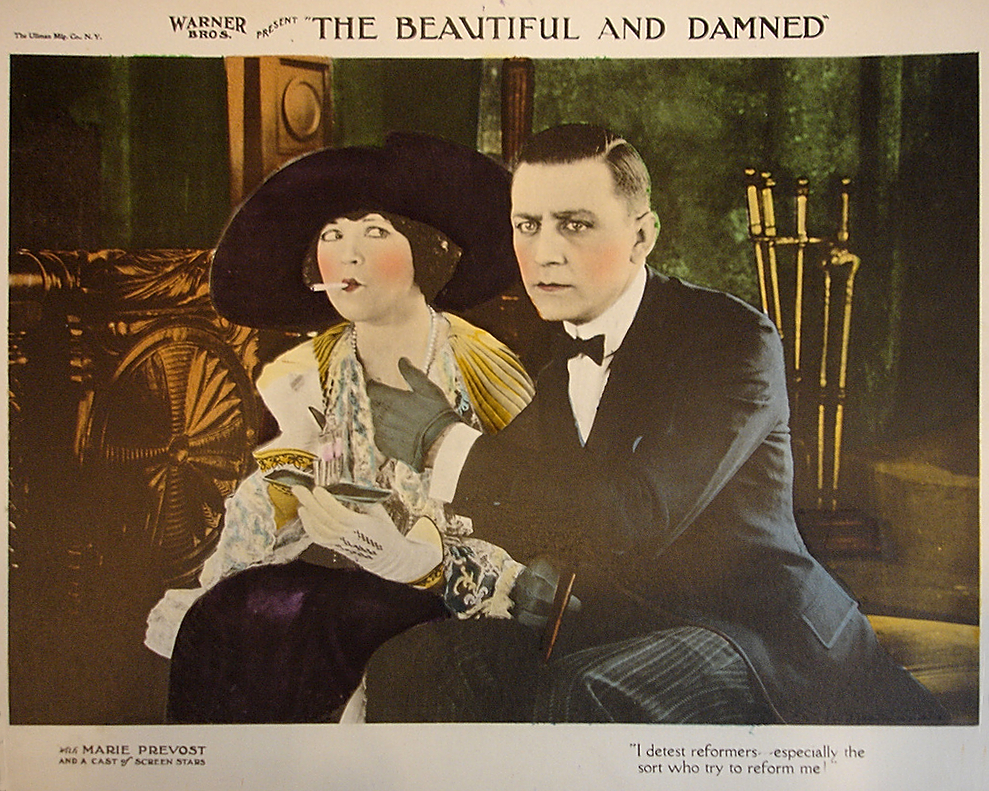

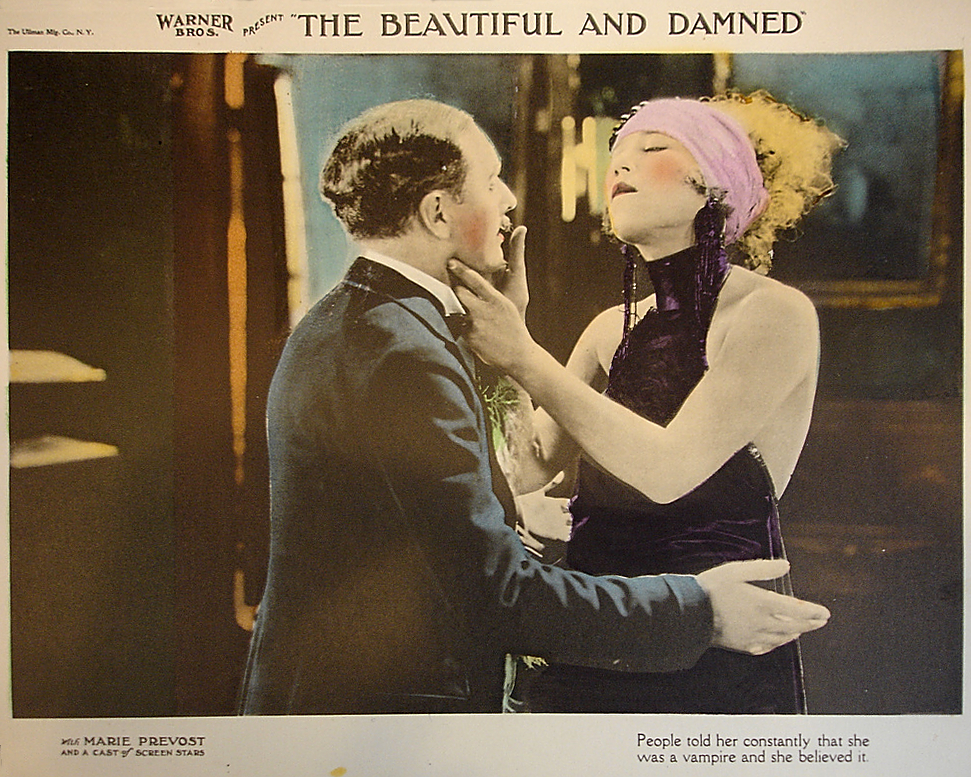

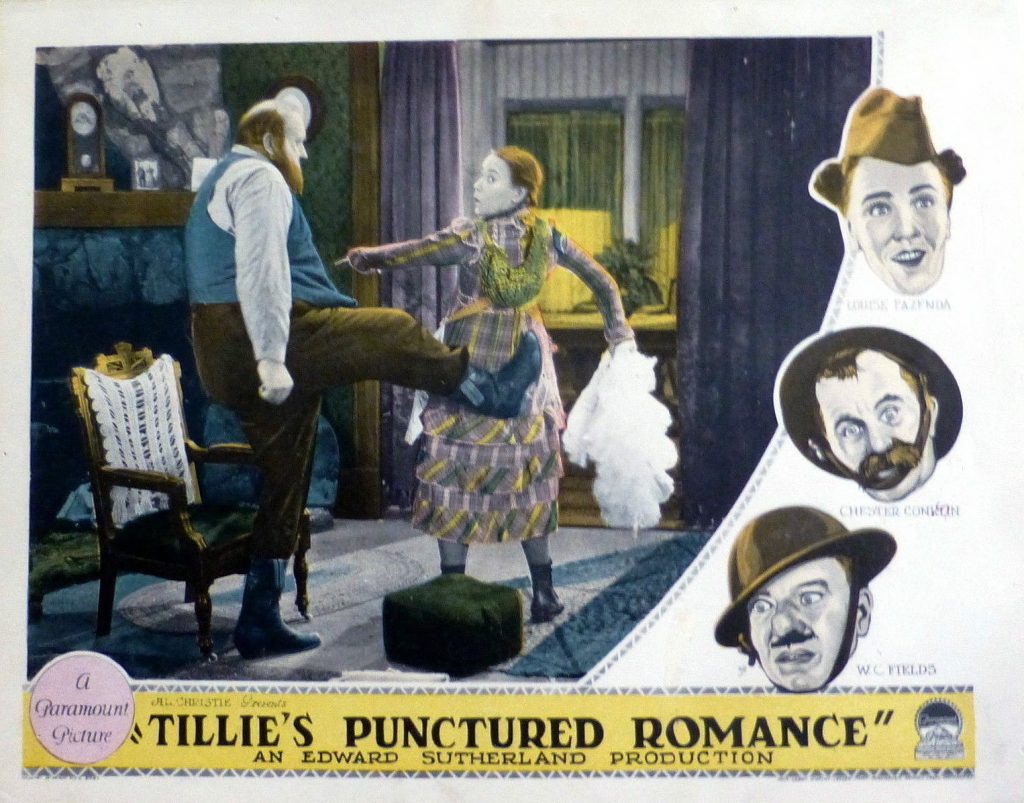

Harlan joined Prevost at Warners and together they starred in the studio’s screen adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Beautiful and Damned (Sidney Franklin, 1922) in which Prevost maintained her flapper image as the modern, emancipated and sexually liberated Gloria, a partygoer and socialist. This role lent her image an extra degree of sophistication than any of her previous ones. Appearing regularly thereafter in Warner productions advertised as ‘Classics of the Screen’ meant that Prevost was elevated to the status of prestige player alongside other leading members of Warners’ stable of stars, such as Louise Fazenda, Harry Myers, May McAvoy, Monte Blue and Irene Rich.

Director Sidney Franklin helped to refine Prevost’s acting method and image when working with her on subsequent films such as Brass, a romantic drama in which she starred alongside Monte Blue and Irene Rich.

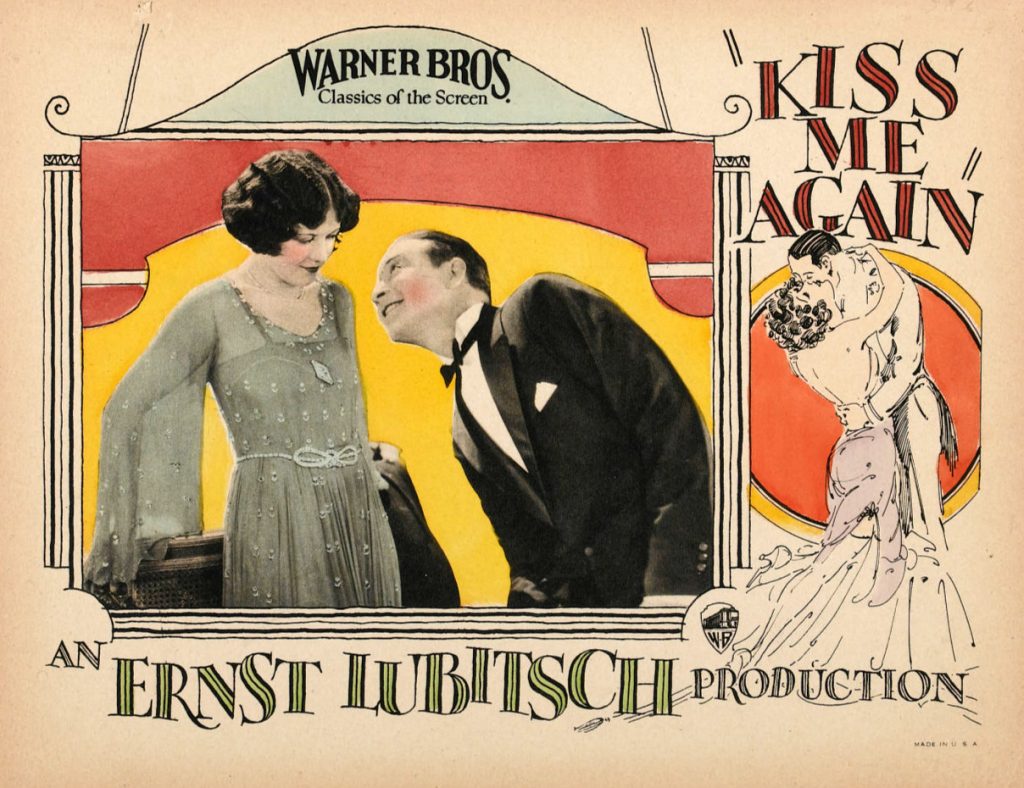

Despite her marriage to fellow Warners’ contract player Kenneth Harlan in 1924, Prevost was repeatedly cast opposite Monte Blue during the mid-1920s. They appeared together, for instance, in The Marriage Circle (Ernst Lubitsch, 1924), How To Educate a Wife (Monta Bell, 1924), Being Respectable (Phil Rosen, 1924), The Dark Swan (Millard Webb, 1924), Recompense (Harry Beaumont, 1925), Kiss Me Again (Lubilsch, 1925) and Other Women’s Husbands (Erle C. Kenton, 1926)

Learning from Lubitsch

Prevost’s work with the celebrated German actor-director Ernst Lubitsch at Warners in the mid-1920s not only refined her screen acting technique even further, lending her greater restraint and subtlety in her use of gesture, expression and looks, but also enhanced her sophisticated screen image.

[For more on Prevost’s work with Lubitsch, see Chapter 3 of my book When Warners’ Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018).]

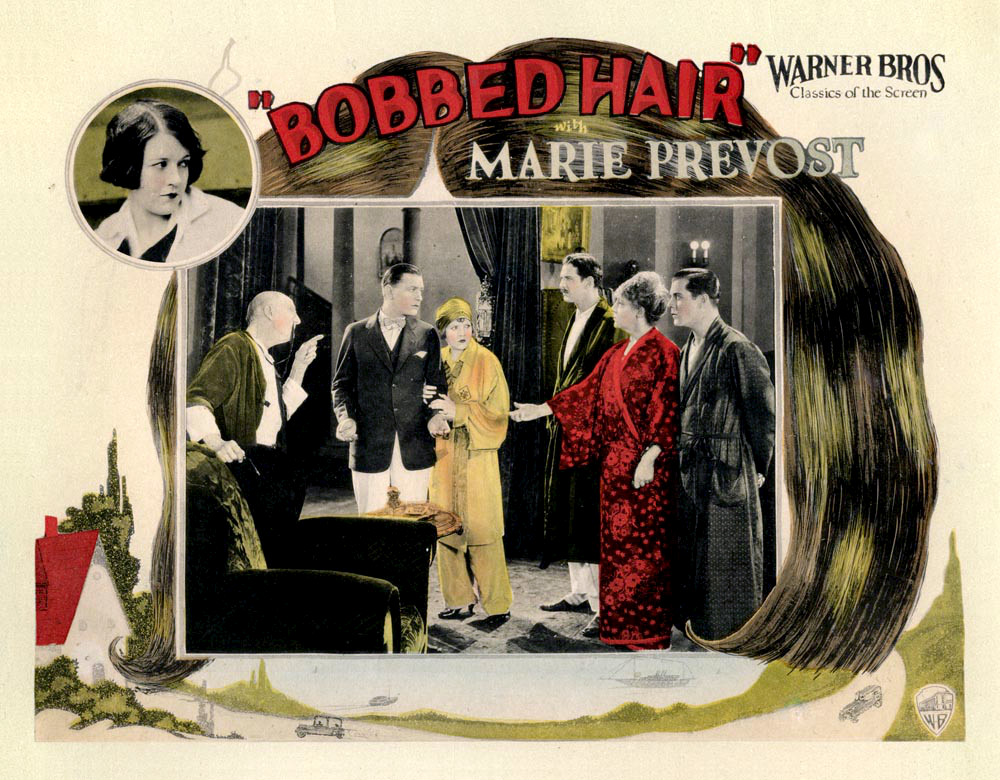

By 1925, Marie Prevost had become one of the most popular and successful stars at Warner Bros. In that year, she produced one of her finest comedy performances alongside her husband Kenneth Harlan in Bobbed Hair (dir. Alan Crosland).

A leading exponent of silent farce

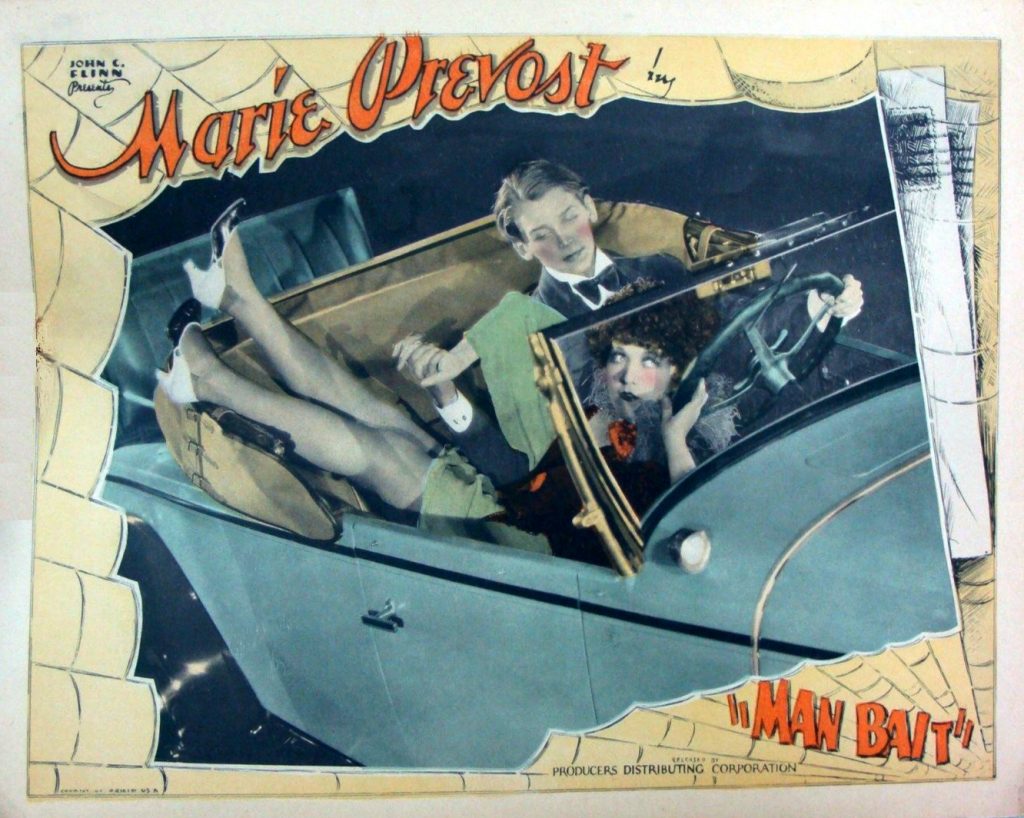

In 1926, as Warners began to forge ahead with its experiments into sound cinema and ‘talking pictures,’ Prevost grew restless and decided to leave, joining the Producers Distributing Corporation, with whom she made the silent romantic comedy Man Bait (dir. Donald Crisp) with a young Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (son of Hollywood aristocrat Douglas Fairbanks, Snr.).

During the formative years of sound cinema, Prevost scored major hits with silent versions of stage farces, notably Up in Mabel’s Room (1926) and Getting Gertie’s Garter (1927), both directed by E. Mason Hopper. These had previously been huge hits on Broadway when first staged. A.H. Woods’ production of Wilson Collison and Otto Hauerbach’s Up in Mabel’s Room had run for 229 performances on 42nd Street in New York from the 15 January 1919, attracting huge critical and commercial interest.

Meanwhile, A.H. Woods’ production of Wilson Collison and Avery Hopwood’s farce Getting Gertie’s Garter ran for 120 performances at the Theatre Republic in New York from 1st August 1921, with a cast once more led by actress Hazel Dawn, one of the finest exponents of farce in America.

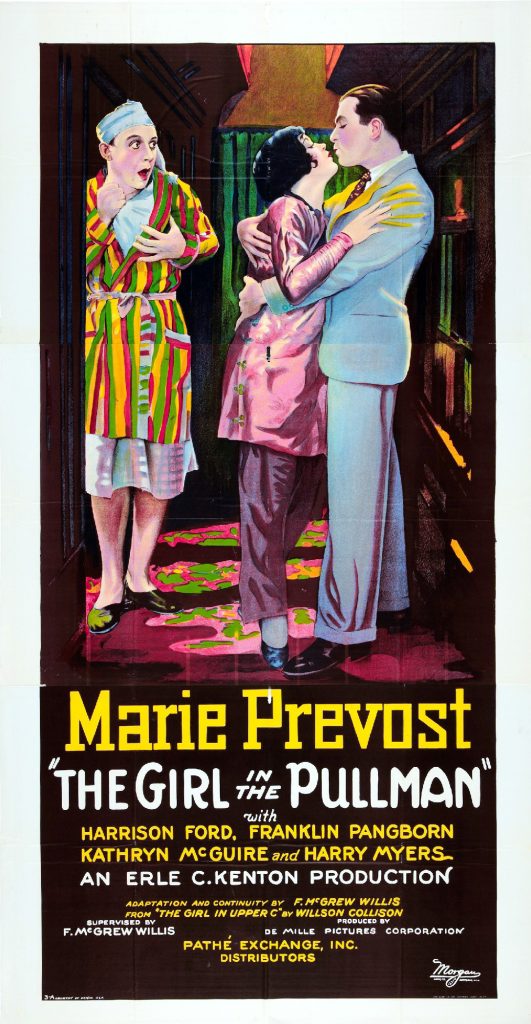

Stepping into Hazel Dawn’s shoes for the silent movie adaptations of these two hugely popular stage plays established Prevost’s credentials as one of the country’s leading screen performers of farce in the late Twenties. A series of smart quality productions for DeMille followed, further establishing Prevost as Hollywood’s foremost female farceur; The Girl in the Pullman (Erle C. Kenton, 1927), Blonde for a Night (E. Mason Hopper, 1928) and The Rush Hour (Mason Hopper, 1928). It’s clear that by the mid to late Twenties, Prevost had found her forte and was sticking to it.

No longer a leading lady

Everything changed for Prevost, however, in 1928. Separated from husband Kenneth Harlan and seeking consolation in a bottle, she piled on the pounds at the very moment that her looks began to fade. As her bloom faded, the intense gaze of the camera recorded and exposed her lack of youth and vitality. This also occurred at the very moment that talking pictures became all the rage after Warners’ sensationally successful part-talkie The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927). Almost overnight, moviegoers became tired of silent farce, preferring musical comedy. Few wanted to hear Prevost’s voice in her first talkie for the Christie Company Divorce Made Easy (Neal Burns and Walter Graham, 1929) since it just didn’t seem match up to her sophisticated image. Her shining, glossy and glamorous look suddenly seemed tarnished and outdated. She quickly found herself relegated to supporting roles in films like The Racket (Lewis Milestone, 1928), Party Girl (Victor Halperin, 1930) and Ladies of Leisure (Frank Capra, 1930).

In Ladies of Leisure, Prevost played second fiddle to Barbara Stanwyck, one of the new faces of the Thirties.

Prevost subsequently supported Joan Crawford in her star vehicle Paid (Sam Wood, 1930) and Marion Davies in the comedy It’s a Wise Child (Robert Z. Leonard, 1931), both at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. She found small roles not only at MGM but also at Columbia, RKO and Universal. At the height (or depth) of the Depression in 1932, she managed to secure a headlining role alongside Jean Harlow and Mae Clarke in Columbia’s Three Wise Girls (Wm. Beading, 1932), yet she was clearly no match for the luminous charms of Harlow at this time.

Also in 1932, Prevost joined the supporting cast of Ginger Rogers’ Carnival Boat (Albert S. Rogell) and Evelyn Knapp’s Slightly Married (Richard Thorpe) at RKO and Universal respectively. Rather sordid (pre-production code) crime dramas followed in 1933, including minor roles in Mae Clarke’s star vehicle Parole Girl (Edward F. Cline) at Columbia and Marian Marsh’s The Eleventh Commandment (George Melford) at RKO.

When she appeared in Margaret Sullavan’s maternal melodrama Only Yesterday (John M. Stahl, 1933), Prevost was little more than a bit-player.

A pitiful end to a glorious career

Prevost either badly needed money in 1935 or just needed to work, a need that forced her to go on taking small roles however humiliating this might be for such a major star of silent cinema. Often these were low-budget, quickly made shorts, such as Keystone Hotel (Ralph Straub), which reunited her with Ben Turpin after 14 years, during which time their careers had gone in such different directions only to bring them back to the same place. Every now and then, Prevost was hired for a more distinguished kind of picture, one more suited to the talents of an actress trained in screen performance by Ernst Lubitsch, such as Paramount’s Hands Across the Table (dir. Mitchell Leisen, 1935), which was based on a screenplay by Norman Krasna and starred Carole Lombard and Fred MacMurray.

When hired again to support Fred MacMurray, this time opposite Joan Bennett in 13 Hours by Air (Mitchell Leisen, 1936), Prevost was reduced to playing a bit-part as a waitress. As her film career drew to a close, she was forced back into playing types rather than individuated named characters, just as she had done at Keystone in the Teens and early Twenties.

Returning to the Warners’ lot at Burbank, the scene of her greatest successes in the mid-1920s, Prevost suffered the further indignity of being cast in uncredited roles in the action thriller Bengal Tiger (Louis King, 1936) and the musical Rom-Com Cain and Mabel (Lloyd Bacon, 1936). Tragically, shortly after the release of the B-Movie Ten Laps to Go (Elmer Clifton, 1936), in which she appeared as a cafe waitress called Elsie, Marie Prevost was discovered dead at her home, apparently drunk and malnourished. The greater tragedy and indignity was that her famous face had been chewed away by her starving pet dachshund. It was a sordid death after years of struggle and humiliation for an actress who had entered the film business in 1915 without any acting training and yet – through talent, intelligence, wit and a great deal of serendipity – had been able to rise to the heights of success and stardom in Hollywood, partly with the help of some of the industry’s most accomplished directors; notably, King Baggott, Sidney Franklin and Ernest Lubitsch.

How to remember her?

An ability to learn quickly on the job had helped transform a good-looking and athletic girl into a glamorous movie star; that is, until taking pictures revealed her to have a voice that failed to live up to her image. Without an refined, melliferous or phonogenic voice, Prevost was sunk, being unable to prevent a rapid descent to the bottom of the pile. Nevertheless, despite the sorry end to her life and career, she deserves to be remembered for more than being the faded alcoholic star whose face was eaten away by her pet dog. Rather, she warrants respect as one of the greatest American exponents of silent screen farce and as a star who made a remarkable transition from a Keystone bathing beauty to an actress respected by no less as personage than, Ernst Lubitsch – one of the world’s most admired and demanding film directors. He was among the first to recognise the subtlety of her art, being able to refine and exploit her talent and skill during the production of several films as Warner Bros. What Lubitsch saw in Marie Prevost surely deserves to be seen and appreciated more widely.

Never a leading lady?

Unlike Ruth Chatterton and Marie Prevost, actress Louise Fazenda was never considered to be a leading lady but, rather, was mostly deemed a ‘character actress.’ For many years, she performed alongside Prevost, both in Keystone films in the Teens and early Twenties, and in Warner productions of the early to mid-1920s. In most cases, she played supporting roles. Nevertheless, her fate was certainly far better than Prevost’s. Not only did her career endure into the sound era, bringing her new creative opportunities, but she also became an important figure in Hollywood as the wife of leading producer Hal B. Wallis.

Despite lacking leading lady status in Hollywood, reporter Adela Rogers St. Johns described Fazenda as ‘The Most Versatile Girl in Hollywood,’ in an article in the movie magazine Photoplay in June 1925 (pp. 84 & 128-9). This was the title of St. Johns’ piece, which opens with the statement that, ‘Of all the people in Hollywood I suppose Louise Fazenda comes nearest to being what is generally called “a character”. And what they actually mean by that … is someone who is honestly without any affectation, different from the ordinary run of human beings, someone with pleasant and lovable eccentricities of dress, taste and manner’ (p. 84). She adds, ‘Upon all these counts, Louise Fazenda, one of the very rare comediennes the screen has produced and one of the best character actresses, stands convicted’ (p. 84). So, for this particular prominent Hollywood journalist, Fazenda stood accused of being ordinary in terms of personality but eccentric in appearance, which effectively undermined her potential as a leading lady.

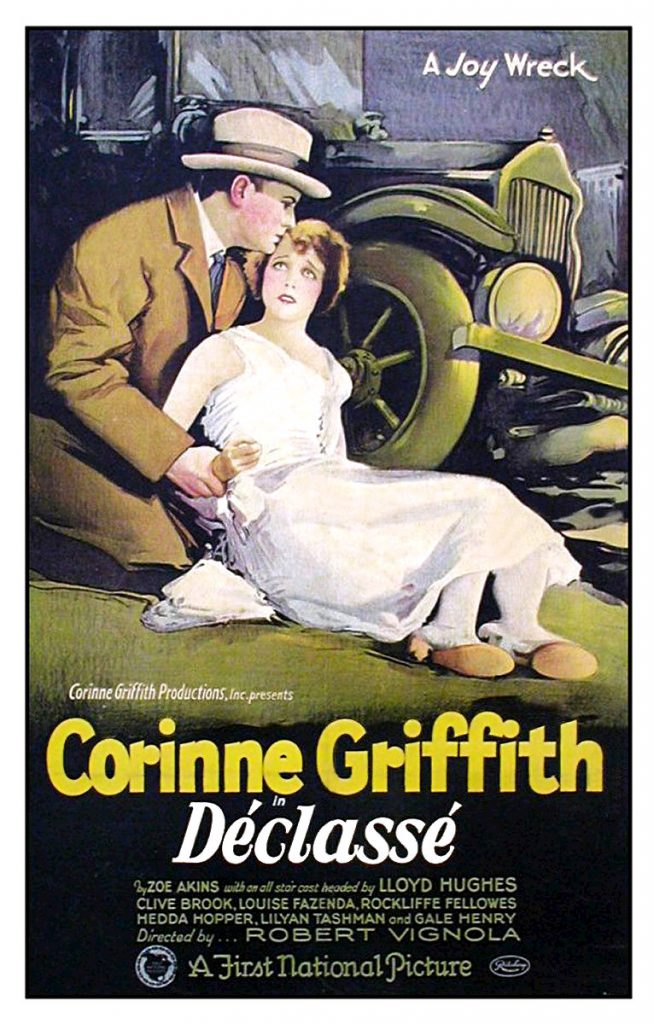

A much more conventional Hollywood leading lady in the Twenties was Corinne Griffith, popularly known as ‘Orchid Lady of the Screen,’ who received an Oscar nomination for her performance in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1928).

Since her film debut in 1916, Griffith had quickly become one of America’s most popularity and powerful stars, especially once she formed her own production company and became the executive producer of her own star vehicles, such as Babs (Edward H Griffith, 1920) and Single Wives (George Archainbaud, 1924).

In 1925, Griffith starred in and executive produced Déclassé for First National, a photoplay based on Zoe Akins’ stage play, which had previously been a big hit for Ethel Barrymore on the Broadway stage. Directed by Robert G. Vignola, Griffith performed the leading role, Lady Helen Haden, while Lloyd Hughes (as Ned Thayer) led a strong supporting cast that included British actor Clive Brook (as Soloman), former Ziegfeld girl Lilyan Tashman (as Mrs Leslie) and future Hollywood gossip queen Hedda Hopper (as Mrs Wildering). A young Clark Gable also made a brief appearance as an extra. Meanwhile, Louise Fazenda joined the supporting cast to perform a major role as Mrs Walton, a character part rather than a glamorous starring role.

Two months after the release of Déclassé, Adela Rogers St. Johns in her Photoplay article ‘The Most Versatile Girl in Hollywood,’ declared that Fazenda was ‘no beauty,’ adding that, ‘I sometimes think that she might have been made into a beauty as well as some others I have seen on the screen.’ St. Johns even noted the qualities that could (or should) have made Fazenda a beauty, such as her ‘glorious, curly, thick hair, in shades of golden brown,’ as well as her ‘intelligent eyes’ and ‘a figure so excellent that she has posed a number of times for famous sculptors.’ Yet despite these impressive attributes, the reporter declared Fazenda to be ‘a woman indifferent to her personal appearance’ (p. 129).

This autographed photograph of Fazenda by leading American photographer Albert Witzel confirms St. Johns’ point that the actress was beautiful, with luxurious hair, intelligent eyes and a fine figure, all attributes that could well have made her a major Hollywood ‘Leading Lady’ in the Twenties. Yet, to me, there seems little here to support St. Johns’ claim that the model for this picture was ‘indifferent to her personal appearance.’ Indeed, on the contrary, she appears not only conscious of her good looks but confident in her ability to attract and hold the viewer’s gaze. So why didn’t she cultivate an image as a glamorous leading lady in her films?

Not enough class?

Maybe the answer to this question lies in her pre-film and early film career and the image she carved out for herself at Keystone in the Teens. Maybe it goes back even further to her childhood. Born to older than average parents in Los Angeles, her father a grocer and her mother a one-time beauty, Louise claims in various interviews throughout her career to have always considered herself to be plain and unattractive from an early age. Indeed, she repeatedly presents herself as a hard-working girl, forced to undertake menial jobs for the good of her family, a kind of Cinderella figure, which was also often featured in her early films at Keystone.

In interviews, Fazenda often spoke of her childhood poverty, including how she sold newspapers and did chores for neighbours as a schoolgirl. Later on, lacking the resources to attend college, she became an assistant to a doctor, then a dentist and finally a tax collector before joining a small stock acting company in Long Beach, California. This led to her becoming an extra at Universal prior to joining Ford Sterling’s comedy company and then Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studio, where she found a more permanent position, lasting seven years. Here, she was chased by the famous Keystone Kops and chased after Teddy the Great Dane, as well as a succession of ducks and geese in a vast number of short silent comedies, for the princely salary of $35 a week.

Interviewed by a reporter for the Toledo Blade in May 1925, Fazenda declared, ‘Do I mind looking so freakish in my comedies? Well, I suppose I must say that I do’. In an article entitled ‘Louise Fazenda Cherishes Ambition to Become “One-Girl Style Show”’ on 4th May, she added that ‘When I first entered pictures I had ambitions to play drama, but the directors insisted I was a comedienne, and kept me at it until I began to believe it myself.’ She went on to say that, ‘The character of a dumbellish sort of person – well meaning but always getting in the wrong was one that had immense possibilities.’ So her casting as a comic eccentric (with her iconic kiss curl on her forehead marking her out and making her recognisable to moviegoers) prevented her from becoming a glamorous movie queen like Gloria Swanson but provided her with a durable and popular screen persona that not only found favour with early moviegoers but also provided her with a steady supply of lucrative and creative work.

The immense possibilities of Louise Fazenda

Louise Fazenda appeared in her first film in January 1913. This was a short western called The Romance of the Utah Pioneers (Charles Farley) made at Bison Motion Pictures. Her next film, released in August, was made at the Independent Moving Pictures Company of America (IMP). Called Poor Jake’s Demise, it was a comedy starring Max Asher, who subsequently appeared in a number of ‘Mike and Jake’ comedies alongside Harry McCoy as Jake. Fazenda appeared in no less than 15 of these over the next two years in the role of Louise.

She also starred as Mandy in the comic shorts The Joy Riders and For Art and Love, both directed by Allen Curtis in 1913 and featuring Max Asher, Harry McCoy and Bobby Vernon at Universal Film. In a series of shorts featuring Max Asher as Lazy Louis Schultz, Fazenda played his wife: Lazy Louis (1913), She Would Worry (1913), Schultz the Barber (1914), Love and Electricity (1914) and What Happened to Schultz (1914), all directed by Allen Curtis. In other Schultz films, she played Schultz’s daughter Mandy: Oh! What’s the Use? (1914), Love and Graft (1914) and Across the Court (1914), again all directed by Allen Curtis. She was also directed by Curtis playing her character Mandy in He Married her Anyhow and Love Disguised in 1914.

The following year, Fazenda was repeatedly cast as Ma Ambrose in a series of Ambrose films at Keystone starring Mark Swain. These included, Wilful Ambrose (David Kirkland, 1915), Ambrose’s Sour Grapes (Walter Wright, 1915), Ambrose’s Little Hatchet (David Kirkland, 1915) and Ambrose’s Fury (Dell Henderson, 1915), to name just a few. Two years later, still at Keystone and with many more films to her credit, she regularly played a character called Maggie in a series of films directed by Frank Griffin, including Maggie’s First False Step (1917), with Wallace Beery as the villain, Her Fame and Shame (1917) and The Betrayal of Maggie (1917). Later on, in 1919, Mack Sennett starred her in the film Hearts and Flowers (Edward F. Cline) alongside Ford Sterling and Phyllis Haver.

She also starred in Treating ‘Em Rough (Fred Jackman) with Ford Sterling and Teddy the Dog, in a film written by Malcolm St. Clair. In the same year, she played a small role in a Ben Turpin comedy called Salome vs. Shenandoah (Ray Grey, Ray Hunt and Erle C. Kenton) that featured Marie Prevost as an ingénue, with Ford Sterling as her father. Prevost and Fazenda previously appeared together in Those Athletic Girls (Edward F. Cline and Hampton Del Ruth, 1918).

They subsequently performed together in many films, including in Her Screen Idol (Edward F. Cline, 1918) and Down on the Farm (Ray Gray, 1920), in which Fazenda had the greater part.

Beautiful and damned

Two years later, Prevost and Fazenda both joined Warner Bros. to appear in The Beautiful and the Damned, Prevost as the leading lady and Fazenda as a member of the supporting cast. Fazenda had ten years experience and well over a hundred films to her credit when Warners hired her to play the small role of Muriel in its adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, supporting Kenneth Harlan as Anthony Patch and Marie Prevost as Gloria.

Thereafter, Fazenda was retained at Warners, becoming a key member of their stock acting company, performing supporting roles in Main Street (Harry Beaumont, 1923), based on the novel by Sinclair Lewis and adapted for the screen by Julien Josephson (and released April 25, 1923), which starred Florence Vidor and Monte Blue. But it was later in the year, in September, that Fazenda made a much greater impression in her supporting role in Warners’ adaptation of Avery Hogwood’s enormously successful stage comedy The Gold Diggers (1919) about a group of struggling showgirls who seduce a group of well-to-do Bostonians despite their suspicion of the girls’ gold-digging motives.

Adapted for the screen by Grant Carpenter and directed by Harry Beaumont, The Gold Diggers photoplay starred Hope Hampton, John Harron, Anne Cornwall and Wyndham Sterling, with Louise Fazenda as the funniest of all the female characters, Mabel Munroe. Warners released the film on September 22, 1923, with a considerable amount of fanfare and the critical response was largely positive, notably for Fazenda.

Indeed, even prior to the film’s release, on the 13th September, trade journal Variety announced that, ‘Warners have turned out an entertaining film of its character and kept it within bounds, even passing up the chance against the possible temptation to do anything in it that would bounce back against the stage or screen’. It went on to state that the ‘piece has plenty of laughs in the action and in the sub-titles,’ and that ‘Louise Fazenda plays it well up all of the time in the principal comedy role while Hope Hampton does a surprisingly good performance’. The Variety reviewer even added that, ‘Miss Fazenda, figuring the panto and absence of dialog in the original role, does just as well here if not better than Jobyna Howland did in the similar part that established Miss Howland [on Broadway in 1919]. And that’s going some for this girl of the screen, as there was never a fatter role written for a woman in a spoken piece’. This review ends by assuring readers that, ‘Even the prudes will like the way the Warners have done this picture and the Warners have done it well’ (ibid.).

As the above images (which where originally used to promote the film in 1923) suggest, even without Avery Hogwood’s witty lines, the part of Mabel in The Gold Diggers enabled Fazenda to steal the show with a vivacious and often grotesque display of physical comedy that including heavy doses of ‘mugging’ and slapstick. Her willingness to sacrifice her dignity for the sake of making the audience laugh made her an outstanding performer in this movie but it also robbed her of any change of presenting herself onscreen as a ‘lady.’ Yet maybe what lay behind this strategy (if it was, indeed, a conscious strategy) was the idea that ‘character actors’ typically sustained longer careers in Hollywood than stars, particularly female stars.

[For more on Louise Fazenda and The Gold Diggers (1923), see Chapter 2 of my book When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 (2018), notably pages 36-39.]

Following her appearance in The Gold Diggers, Fazenda became a stalwart of the Warner lot, appearing in no less than nine films in 1924, including Being Respectable (Phil Rosen) with Marie Prevost and Monte Blue, and The Lighthouse by the Sea (Malcolm St. Clair), an Owen Davis story transformed into a vehicle for the studio’s canine star Rin Tin Tin.

A Hollywood freelancer

Thereafter, Fazenda worked for a range of Hollywood studios, securing work at Paramount, MGM and Universal, as well as Warners, to make 11 films in 1925. Clearly, she was in demand. At Warners, Alan Crosland directed her in Compromise, with Irene Rich and Clive Brook, and Bobbed Hair, with husband-an-wife team Marie Prevost and Kenneth Harlan, in 1925. The following year, however, she scored a major success with another photoplay based on a stage play by Avery Hopwood (his most commercially successful stage play, in fact), the comic murder mystery The Bat. After opening at the Morosco Theatre on the 23rdAugust 1920, this play continued to run there for a remarkable 867 performances until September 1922, while six touring companies took the show across the USA, breaking box-office records everywhere. In January 1922, it began a successful run of 327 performances at the St. James’s Theatre in London, again breaking attendance records. Hopwood sold the motion picture rights for The Bat (for $50,000) to director-producer Roland West, who made the photoplay in 1926, with Louise Fazenda and Emily Fitzoy in the leading roles.

In 1927, Fazenda continued her association with Warners by starring in The Gay Old Bird ( Herman C. Raymaker) and, in November, by marrying one of the company’s most up-and-coming employees, a publicist who was to become one of studio’s most important producers after 1930, his name – Hal B. Wallis – becoming a by-word in quality by the end of the Thirties.

In 1928, as talking pictures became the latest craze, Fazenda continued to appear in silent comedies, although increasingly they began to seem old-fashioned and she was in danger of becoming outdated.

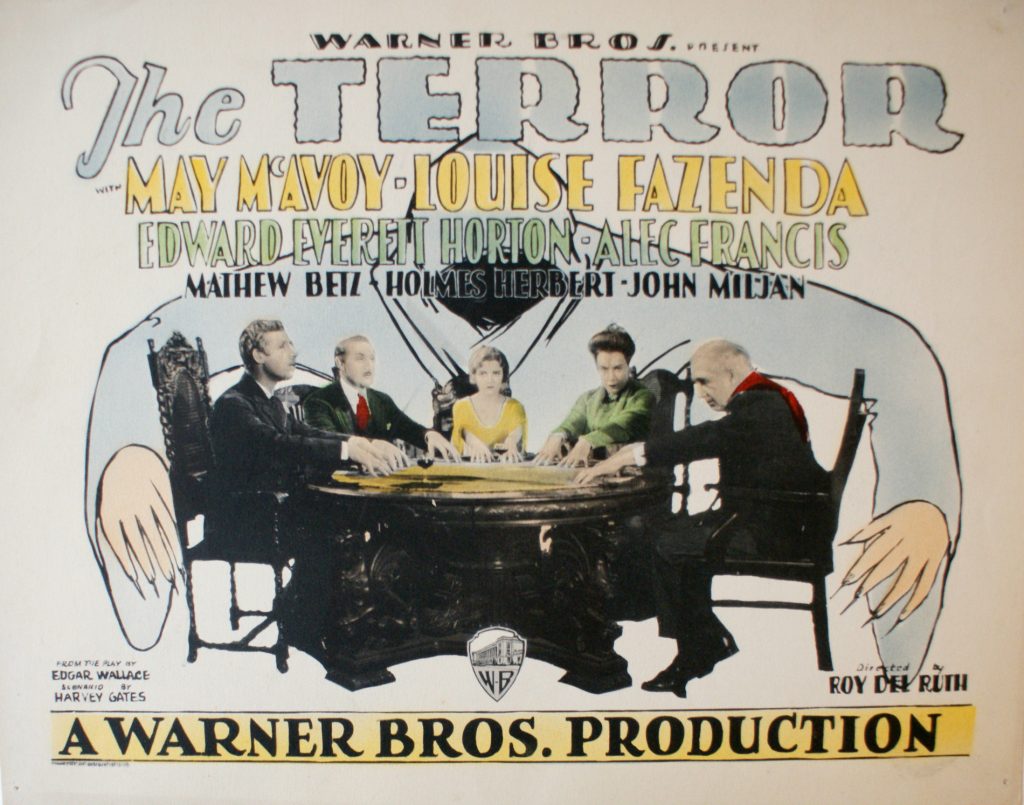

Yet, it was also in 1928 that Fazenda made her first appearance in a talking picture. This was the Warner thriller The Terror (Roy del Ruth), in which Fazenda co-starred with May McAvoy, being supported by Edward Everett Horton and John Miljan.

In talking pictures, great and small

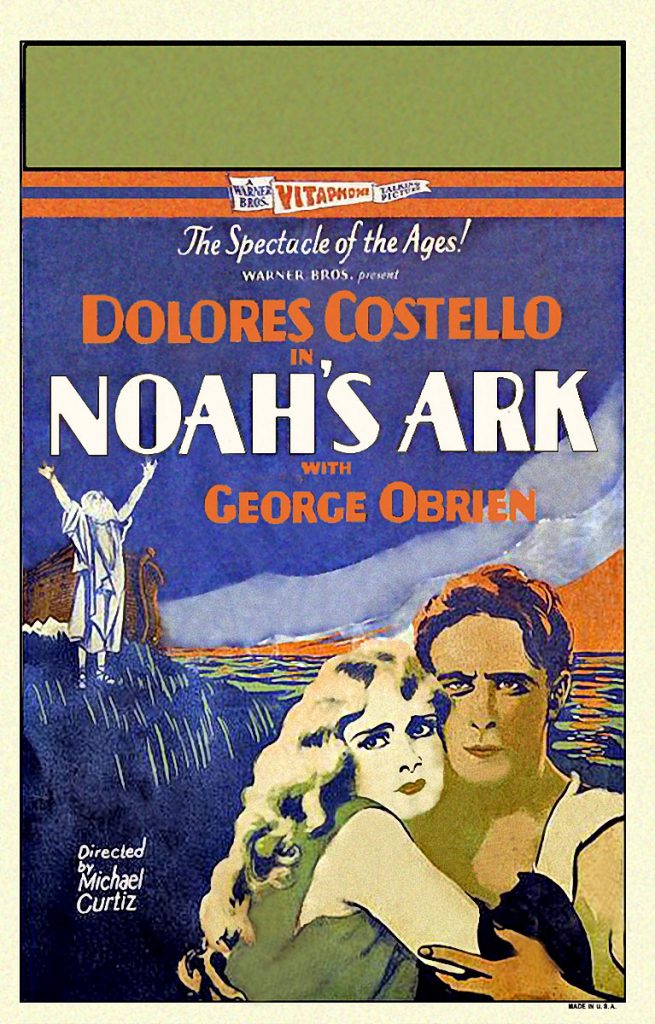

Talking pictures presented Fazenda with a new set of opportunities to display her vocal skills and she subsequently appeared in some of Warners’ most important sound productions, including the epic Noah’s Ark (Michael Curtiz, 1929). Released on the 1stNovember 1928, this proved a massive hit with audiences worldwide. Based on a story written by Darryl F. Zanuck, taken loosely from the Old Testament Bible, it was adapted into a screenplay by Anthony Coldeway with inter-titles by De Leon Anthony. The film boasted an incredibly large supporting cast that included George O’Brien, Noble Johnson, Myrna Loy and thousands of extras (one of whom was a young John Wayne), as well as hundreds of animals. Fazenda had a small role as a tavern maid in this monster of a movie. Although it cost over a million dollars to produce, it took twice that amount at the box-office, which contributed significantly towards an annual profit at Warner Bros. of over $14 million, enabling the company to buy out First National studios shortly after the Wall Street Crash of October 1929.

Fazenda also featured briefly in another epic Warner production in 1929, the grandly titled The Show of Shows (John G. Adolfi). This featured almost every star under contract at First National and Warner Bros. at this time. As well as a clear demonstration of the studios’ impressive stable of stars, it was also a testing ground to determine which silent stars had the ability to endure in the new era of talking pictures. Louise Fazenda joined a long line-up that included Mary Astor, John Barrymore, Richard Barthelmess, Noah Beery, Monte Blue, Jack Buchanan, William Collier Jr., Betty Compson, Dolores and Helene Costello, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Winnie Lightner, Beatrice Lillie, Myrna Loy, Shirley Mason, Patsy Ruth Miller, Carmel Myers, Ben Turpin, Lois Wilson and Loretta Young. Many of these were soon to leave the industry, either temporarily or permanently. Others survived, while some even prospered.

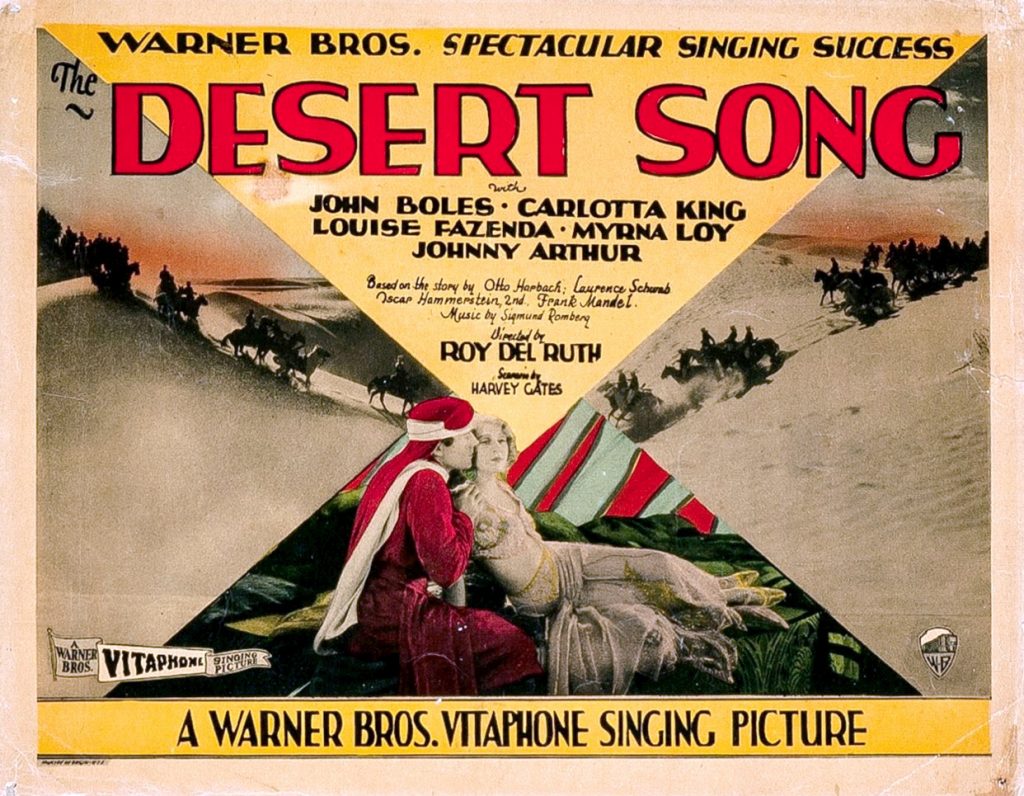

In 1929, Louise Fazenda (aka Mrs. Hal B. Wallis) not only appeared in Noah’s Ark and The Show of Shows but also had major supporting roles in the musicals The Desert Song (Roy del Ruth) and On With the Show! (Alan Crosland).

In 1930, she appeared alongside Lilyan Tashman and Zazu Pitts in Frank Mandel’s musical comedy No, No, Nanette (Clarence G. Badger) and continued to prosper in musicals thereafter, including in Spring is Here (John Francis Dillion, 1930) and Oscar Hammerstein II’s Viennese Nights (Alan Crosland, 1930). For an actress whose professional experience had been almost entirely in silent films, this was a significant achievement.

When, in 1933, Paramount produced an all-star production of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland with Charlotte Henry as Alice, Gary Cooper as the White Knight, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, W.C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty and Edward Everett Horten as the Mad Hatter, Louise Fazenda was cast as the White Queen. Directed by Norman Z. McLeod and adapted to the screen by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, this had a huge cast, including actors destined to become some of the biggest stars of studio era Hollywood. Over the next few years, Fazenda supported some of the most popular Hollywood stars of Thirties, including Al Jolson and Kay Francis in Wonder Bar (Lloyd Bacon, 1934), Dick Powell and Joan Blondell in Broadway Gondolier (Lloyd Bacon, 1935), Dick Powell and Ruby Keeler in Colleen (Alfred E. Green, 1936), and Ruby Keeler in Ready, Willing and Able (Ray Enright, 1937), being responsible for much of the comedy in these musical comedies.

On the 18th July 1935, Regina Crewe, film critic of the New York American, described the Broadway Gondolier as a ‘lively, lilting comedy-with-music’ (courtesy of the composers Harry Warren and Al Dubin), while declaring that, ‘We give Louise Fazenda first feminine spot for a truly hilarious portrayal of the sentimental cheese dowager.’ Later, on the 31st July, the New York American film critic reported that Fazenda, ‘In spite of her success as a comedienne and the fondness in which she held by the fans, … refuses to sign contracts, whether for long or short terms. She prefers to free lance and to take those roles she likes when, as and if she can break from her own schedules.’ Having given birth to a son (Brent, taken from his father’s middle name) in 1933, Fazenda was much more selective about roles at this late stage of her film career. These included regular parts at Warners and many others with rival studios. They also included major and minor roles. A major role, for instance, included co-starring in the comedy romance Doughnuts and Society (Lewis D. Collins, 1936) with Maude Eburne as a working-class woman who attempts to become lady in high society after coming in to a small fortune.

After years of working and squabbling together in the kitchen of a small diner, Kath (Fazenda) and Belle (Eburne) become estranged after Belle has received $50,000 from a gold prospector for a piece of land and uses her newfound wealth to launch her daughter in high society (with almost disastrous consequences). Spurred on by her former friend’s social elevation, Kate (the more sensible and business-minded of the two women) establishes an inner-city multi-storey car park to improve the prospects of her son, enabling him to marry Belle’s daughter Joan (Ann Rutherford).

In the image featuring in the lobby card above, Kate (in the middle) arrives at Belle’s swanky party with her son Jerry (Eddie Nugent) in a hired dress suit. Disaster and comedy ensue when Kate’s uncomfortable shoe containing $500 is stolen by a dog and she chases it around the room creating chaos and humiliating a furious Belle in front of her new well-to-do associates (most of whom are fakes on the make). This scene recalls many of those Fazenda once performed with Teddy the Dog at Keystone despite her being less agile than in her early days of silent film comedy. It was also an indication that the increasingly eminent Mrs. Hal B. Wallis was still prepared to make a fool of herself on screen with some pretty basic slapstick.

The lady lingers

In 1936, the film critic Irene Thirer published an article in the New York Evening Post entitled ‘The Beauts Come and Go – Funny Fazenda Lingers’ (29 April). Here, she stated that, ‘Of all these girls and others who were to become famous names [might she have had Marie Prevost in mind?] only Louise Fazenda has carried on through the years to current screen success. She wasn’t a beauty – but she was a trouper. When the silent celluloid gave way to sound, it was discovered that Louise could be twice as looney and thrice as amusing. For a while she took time out – to become the mother of Brent Wallis, who’s now turned three.’ Thirer adds that, as a ‘character actress,’ Fazenda ‘is as important to a movie outfit as a Garbo – believe it or not!’

In the year that her son turned four, Fazenda took on five film projects, all small supporting roles but nonetheless crucial to maintaining the comedy quotient of each movie. One such part was that of Mrs. Lavinia Mae Creevey in Kay Francis’ star vehicle First Lady (Stanley Logan, 1937), in which Fazenda plays the august president of the Women’s Peace, Purity and Patriotism League. Another, larger supporting role, featured in Swing Your Lady (Ray Enright) released into American cinemas in January 1938. Starring Humphrey Bogart and Frank McHugh, this musical comedy featured Fazenda as an unconventional female lead, a blacksmith and wrestler in the Ozark mountains.

When reviewing Swing Your Lady, the influential film critic Bosley Crowther declared in the New York Times that ‘of Hollywood’s few rugged ladies who have been definitely typed for punching bags, sparring partners and general strong-arm utility work, Miss Fazenda takes the prize with eight rounds out of ten’ (3rd January 1938). He went on to state that, ‘The movie public has come to regard her as an unpredictable cross between Mother Hubbard and Strangler Lewis’, adding that, ‘you may take it from this reporter, Miss Fazenda is a most genteel and amiable lady.’ Clearly, there was some question at this time regarding Fazenda’s status as a ‘lady’ (leading or otherwise), given the rough and tumble roles she had performed on screen for so long. So Crowther insists on her status as a lady off-screen, claiming in his article that the actress had long since become ‘resigned’ to playing these sorts of roles on-screen, asserting that, ‘It was her training in the old Sennett school of rough-and-tumble comedy which prepared her for the character roles which she plays today’.

Bosley Crowther included in his piece the following quote from Fazenda: ‘I acquired that invaluable knack of – well, we call it spacing – which is so essential to all comedy acting. It’s what you call timing or coordinating all of the factors which go to the effect.’ He also quotes her saying that, ‘Today, of course, even in broad comedy, the customary thing is to under play – to make the character, no matter how comic, believable. But the elements of pantomime are the same for the modern fashion as they were for the slapstick school. It’s simply a matter of a little more restraint.’

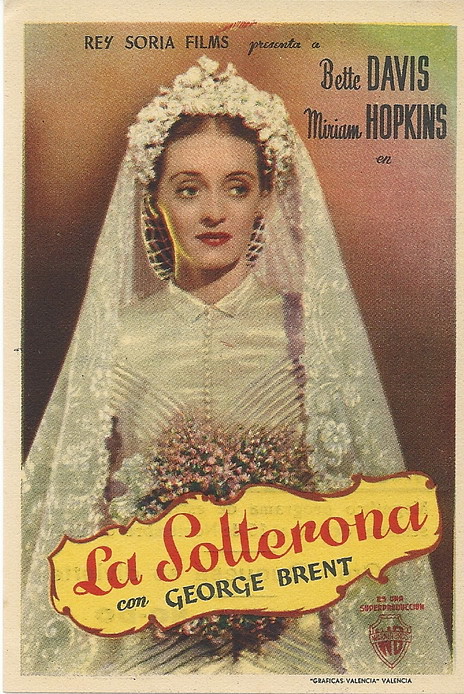

In 1938, Hollywood stalwart Malcolm St. Clair directed Louise Fazenda in her penultimate film Down on the Farm at Twentieth Century-Fox. St. Clair had, of course, directed Fazenda many times before, both at Keystone in Wedding Bells Out of Tune (1921) and at Warners in The Lighthouse by the Sea (1924). Bearing the same title as one of her 1920 Mack Sennett silent comedies, this hour-long sound film seemed like the perfect way to round off her long career, by which time the actress had appeared in over 260 films. Yet she had one more role up her sleeve, a small, almost incidental role in a prestige picture at Warner Bros. starring Bette Davis opposite Miriam Hopkins.

Zoe Akins’ stage play The Old Maid was adapted to the big screen by screenwriter Casey Robinson and director Edmund Goulding in 1939. It was produced by Henry Blanke under the supervision of Fazenda’s husband Hal B. Wallis and it featured the small but ubiquitous role of Dora, the maid, who observes (mostly in silence) the antics of the two main characters played by Davis and Hopkins of a period of twenty years or so. Fazed, the first character to appear on the screen at the start of the movie, appears frequently throughout the film alongside Davis, supplying an unspoken commentary on the events with a series of eloquent and ironic looks. As the trusted and loyal longtime servant Dora, Fazenda is a silent witness to many of the most intimate scenes that occur during the film, occupying a position similar to that of the audience. Throughout, Fazenda maintains a dignified presence throughout this dramatic and emotionally involving movie. It is, perhaps, the kind of film she had wanted to play since her career took off. And yet, realising that boisterous comedy offered her immense opportunities to develop and display her versatility as a performer while sustaining a long career, she had instead ploughed a long and lucrative groove that had sustained her throughout the Teens, Twenties and Thirties.

After The Old Maid, Fazenda decided that she had as much of an acting career as she wanted or needed. Although she gave up professional acting, she remained a prominent figure in Hollywood up until her death in 1962. As the wife of an esteemed and very successful producer, she attended many important industry events, including premieres and award ceremonies. In addition, she devoted herself not only to the care of her son but also to numerous charitable causes, becoming a major benefactress. Off-screen, just as Bosley Crowther had suggested in 1938, she became the perfect lady. Indeed, throughout the Forties and Fifties, Fazenda was one of Hollywood’s true leading ladies d despite being forever remembered as a strange cross between a maternal fairytale character and professional heavyweight champion wrestler.

Re-introducing another of Hollywood’s lost leading ladies

By 1918, 27-year old Irene Rich had two failed marriages behind her when she touted for work as an extra in Hollywood. Despite her age (anything over 25 was considered old in Hollywood at this time) and the fact that she had no acting experience, she secured work at the Thomas H. Ince Corporation and Vitagraph, gaining a sufficient footing in the film industry to base her future career upon.

So rapid was her rise that within three few years she was widely regarded as one of Hollywood’s most glamorous leading ladies.

Irene Rich became a familiar face in the USA after supporting Will Rogers in a series of films from 1920 to 1922, including Water, Water, Everywhere (1920), The Strange Boarder (1920), Jes’ Call Me Jim (1920), Boys Will be Boys (1921) and The Ropin’ Fool (1922). These were mostly male action movies aimed at young male moviegoers with stock supporting female roles.

For a while, action adventures aimed at family audiences formed the mainstay of her work, such a Brawn of the North (Lawrence Trimble and Jane Murfin, 1922), starring Strongheart the Wonder Dog, a major rival to Warners’ leading canine star Rin Tin Tin.

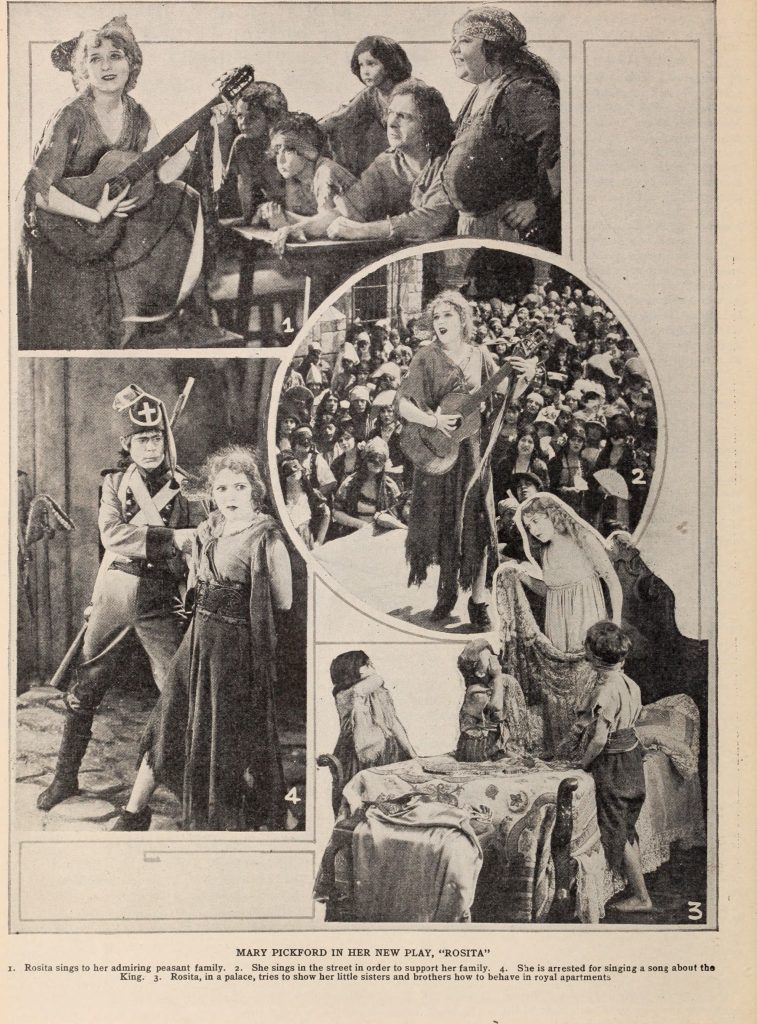

However, her performance alongside Marie Prevost and Monte Blue in Brass (Sidney Franklin, 1923) at Warner Bros. brought about a complete change of pace for Rich. It was shortly after making this film that Rich played a key role in securing a contract at Warners for the celebrated German director Ernst Lubitsch, who directed her in Mary Pickford’s star vehicle Rosita from March to May 1923. In this film, Rich had a major supporting role as the Queen.

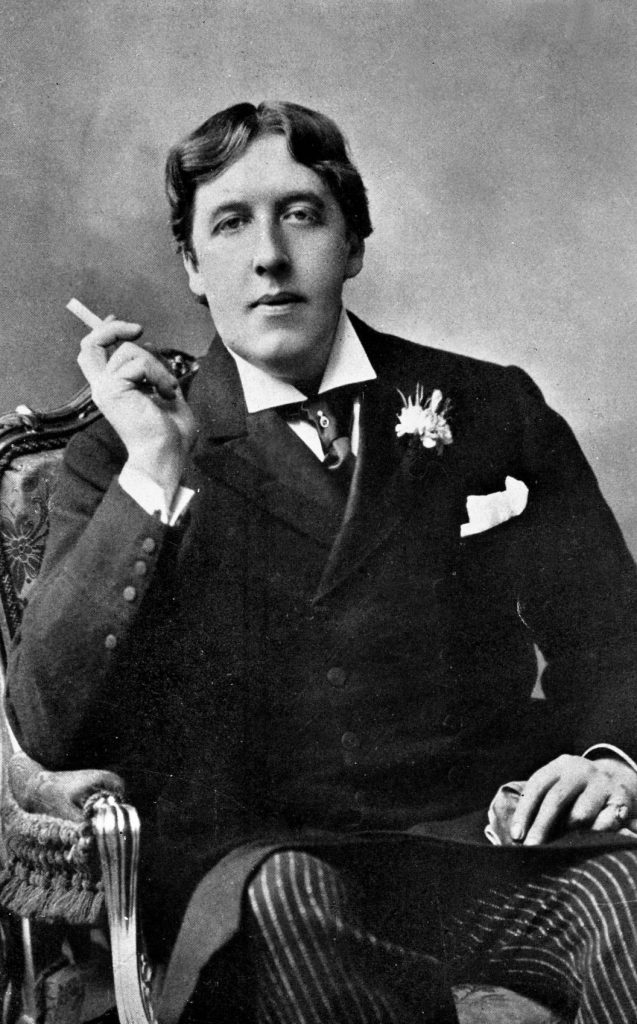

Rich was rumoured to be the mistress of Jack Warner at that time and used this connection to arrange for Lubitsch to meet his older brother Harry Warner, President of Warner Bros., which eventually resulted in Lubitsch signing a deal to direct 6 films at Warners over 3 years. In one of these, Rich was cast as one of Oscar Wilde’s most fascinating characters, Mrs Erlynne. She was one of the main characters in Oscar Wilde’s play Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), which had run on Broadway at the Palmer Theater on 30th Street in New York for 200 performances over a period of 8 month in 1893.

Silently sophisticated: Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925)

While following the structure of Wilde’s original stage play, Lubitsch’s silent photoplay of Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925) features a number of extra scenes, including a scene of Lord Windermere visiting Mrs Erlynne at her house on Curzon street and writing out a large cheque with which she can settle a pile of bills. Another extra scene takes place at the races, where Mrs Erlynne is spied upon by various members of the Windermere set, including the Duchess of Berwick, and where she attracts the interest of Lord Lorton. There is another in which Mrs Erlynne’s admirer Lord Lorton first calls on Mrs Erlynne at her home and another in which he suspects she has been entertaining another suitor. These scenes not only introduce two new locations to the drama but also give Mrs Erlynne a greater role, in which we witness her domestic life, generating a greater amount of sympathy for her character than in the original play.

Irene Rich’s characterisation of Mrs Erlynne in Lady Windermere’s Fan portrays her as a clever, beautiful and stylish mature woman intent on making her way back into London society after years of ostracism, having once deserted her husband and child to run off with a lover. That child is now Lady Windermere (May McAvoy) and, in order to protect his wife from this knowledge and the scandal that would be caused if this became public, Lord Windermere (Bert Lyell) agrees to supply the notorious Mrs Erlynne with the necessary funds to cover the costs of her house (and staff) on Curzon Street in London’s exclusive Mayfair, her stylish wardrobe and other expenses.

One of the high points of the drama is when Mrs Erlynne is finally reunited with her daughter at Lady Windermere’s exclusive birthday party, to which Mrs Erlynne has been expressly forbidden by the young noble woman, suspecting that she is her husband’s mistress (never suspecting the truth that she is in fact her own mother). Lady Windermere has threatened to strike Mrs Erlynne with the fan that her husband as given her as a birthday gift but, upon being presented to her, the young woman simply drops her fan to the floor in her confusion and discomfort. Later on, the fan becomes a piece of incriminating evidence when it is discovered in the bachelor apartment of Lord Darlington (Ronald Colman).

Here, it is discovered by Lord Lorton (Edward Martindel) and recognised by Lord Windermere as the gift he had given his wife earlier that same day. Suspecting that she is hiding somewhere in Lord Darlington’s apartment, and suspecting an illicit tryst, Windermere insists that Darlington explain the matter. Darlington, however, has no idea that Lady Windermere, with whom he has been flirting, is hiding in the room next door; that she has fled from her party believing that her husband has insulted her by inviting his mistress into their home and so, in retribution, she has finally decided to accept the amorous advances of the younger lord. Lady Windermere’s ruin is only prevented when Mrs Erlynne enters the room and claims the fan on the pretext that she had picked it up at the party by mistake.

The assembled all-male company (including her own would-be suitor Lord Lorton) are all convinced by this lie, assuming that she is here as the mistress of Lord Darlington. While this jeopardises any chance of her own marriage prospects (by confirming her scandalous reputation as a loose woman), this act of maternal sacrifice secures the good name, reputation and marriage of her daughter (who remains ignorant of that fact that she is her mother).

While Mrs Erlynne presents herself in this compromising situation, Lady Windermere is able to escape from the apartment without being seen. The next morning, when Mrs Erlynne arrives at the Windermere’s home to return the fan to Lady Windermere, the young woman reveals her gratitude to the older woman, receiving her (at last) as a friend in her home, while Lord Windermere evidently now despises the woman and so leaves the room in disgust upon her arrival. Having made peace with her daughter, without betraying the secret of her true parentage, Mrs Erlynne leaves the Windermere’s home in order to proceed to France. As she does so, she meets her former suitor Lord Lorton in the street and astonishes him by telling him that, on account of his disgraceful behaviour the previous night (when he discovered her in Lord Darlington’s apartment), she has decided not to marry him after all. He is so stunned by this news, that he follows her into her luggage-laden vehicle and they drive off together, restoring the possibility of Mrs Erlynne’s marriage into the English aristocracy and her consequent re-entry into London society (after a suitable time spent aboard).

Mordaunt Hall, in his review in the New York Times on the 28thDecember 1925, stated that although ‘she does not look like Wilde’s Mrs Erlynne,’ Rich ‘gives a competent portrayal of the rôle, being dressed in interesting fashion, especially when she dons a turban and has curls of her dark hair protruding on each cheek’. Later, on the 13th January 1926, a reviewer in Variety stated that the film was ‘Beautifully cast in so far as the five leading players are concerned, well acted by them, and with clever touches of the director’s art furnished by Lubitsch.’ It was also pointed out that Irene Rich was successfully cast against type here as a disreputable woman.

A series of ‘corking’ performances

A leading role in a Lubitsch film based on an Oscar Wilde play significantly enhanced Irene Rich’s reputation as a prestige performer at the end of 1925, even if she was playing a woman with a scandalous reputation. By this time, the actress had grown accustomed to receiving rave reviews for her screen performances. For instance, on 21stJanuary 1925, Variety had declared Warners’ photoplay of Willa Cathers’ novel A Lost Lady (Harry Beaumont, 1924) to be a ‘corking picture for Irene Rich’ despite it not being a great picture as a whole, observing that the film was ‘only memorable for the performances of Miss Rich’. Otherwise, the reviewer declared, the film suffered from ‘inconsistent’ continuity and an unconvincing story. The reviewer also stated categorically that ‘Miss Rich is unquestionably superior to the story in this instance’. She received more praise in Variety on the 28th October 1925 for her performance in Compromise, in which she led an impressive cast that included Clive Brook and Louise Fazenda. On this occasion, the reviewer declared that ‘Miss Rich … gives a corking performance opposite Clive Brook’. All of this suggests that by the time Rich appeared on screen as Mrs Erlynne, she had achieved a reputation as a fine screen actor.

As silent films reached their zenith in terms of sophistication in the mid to late Twenties, Irene Rich took her place as one of America’s pre-eminent performers. Her starring roles in glamorous prestige productions such as My Official Wife (Paul L. Stein, 1926), in which she plays a countess in Imperial Russia prior to the revolution, consolidated her image as a sophisticated leading lady and a fine screen actress.

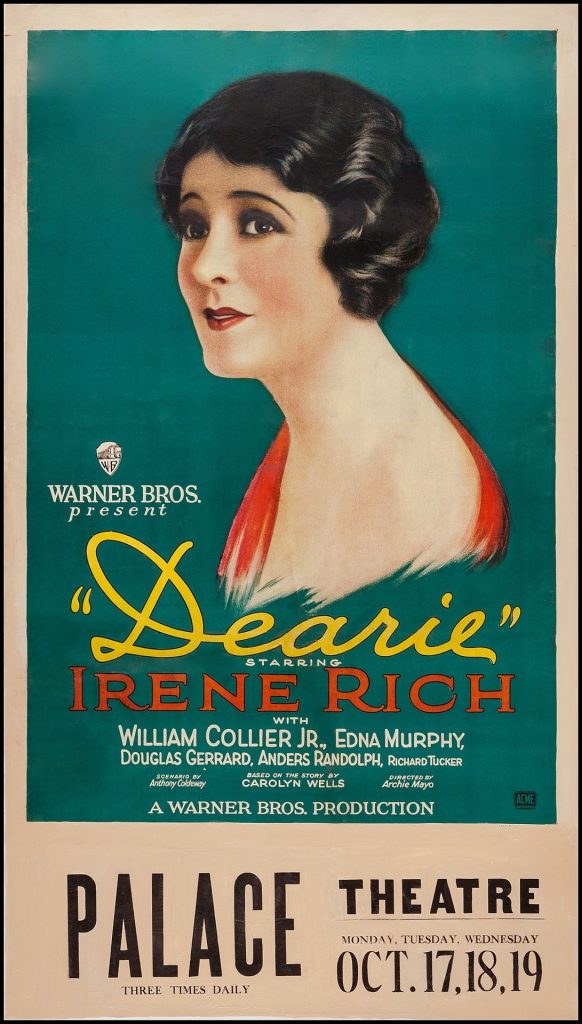

Her dramatic abilities were showcased in the silent maternal melodrama Dearie (Archie Mayo) in 1927 with William Collier Jr. as her son.

As talking pictures became all the rage in America, Rich continued to headline in silent film melodrama, such as Craig’s Wife (Wm. C. DeMille, 1928).

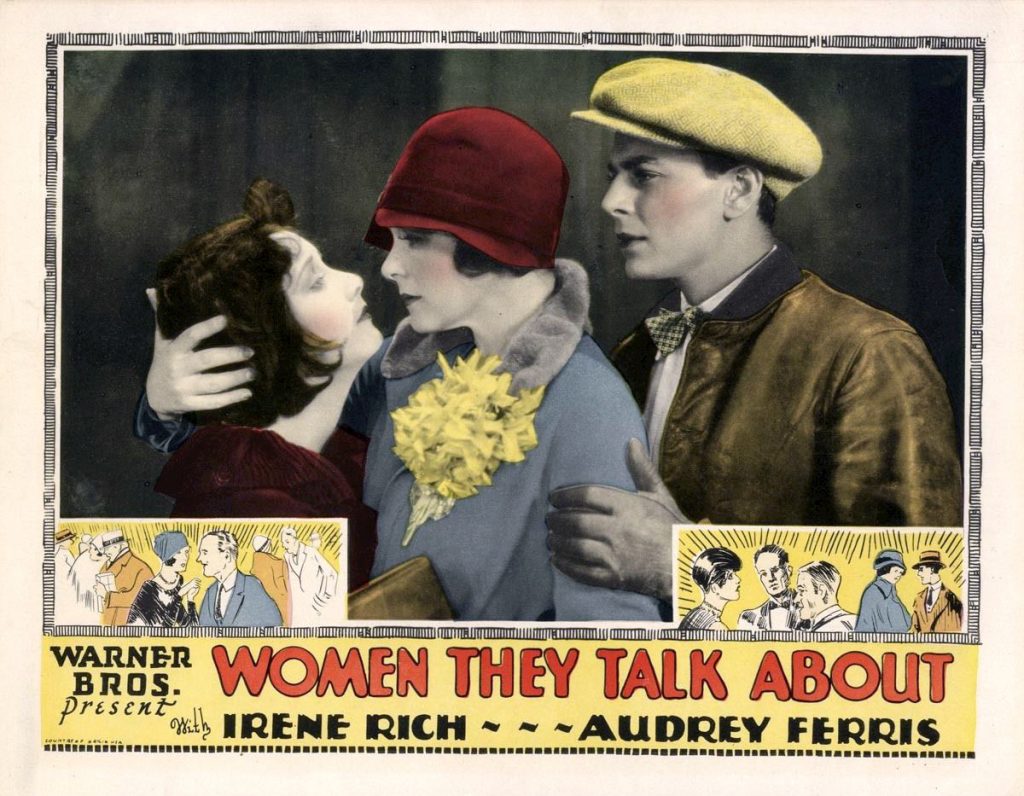

However, Rich also appeared in talking picturesin 1928, such as Women They Talk About (Lloyd Bacon, 1928) and Ned McCobb’s Daughter (Wm J. Cowen, 1928), disproving Louella Parsons’ assertion that Warners would let her go on account that she wasn’t suitable for Talkies.

Yet as Talking Pictures consolidated their grip on the American film industry in 1929 and 1930, introducing new faces to moviegoers (many drawn from Broadway theatre), Rich found herself increasingly relegated to supporting roles. In 1931, for instance, she joined Louise Fazenda to support Evelyn Brent in Paramount’s World War I drama Forgotten Women (Wm. Beading). However, by taking the leading female role in (child star) Jackie Coogan and Wallace Beery’s The Champ (King Vidor, 1931) at MGM, she was able to maintain her star power a little longer while shifting her screen image away from glamorous sophisticated roles to something altogether more mundane and maternal, something more in tune with the depressed early Thirties.

Another series of Will Rogers’ comedies also maintained Rich’s prominence in Hollywood at this notoriously tricky time for silent stars without stage backgrounds, including They Had to See Paris (Frank Borzage, 1929), So This is London (John Blystone, 1930) and Down to Earth (David Butler, 1932).

Yet after 1932, Rich found more regular and lucrative work on radio, only returning to the big screen in the late Thirties in supporting roles in films such as Deanna Durbin’s That Certain Age (Edward Ludwig, 1938) at Universal and Margaret Sullivan and James Stewart’s romantic drama The Mortal Storm (Frank Borzage, 1940) at MGM.

In 1940, she also supported Brian Ahern, Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford and in The Lady in Question (Charles Vidor) at Columbia. Meanwhile, major roles in Westerns came to play an increasingly prominent part in Rich’s career during the Forties, most notably in Queen of the Yukon (Phil Rosen, 1940), Angel and the Badman (James Edward Grant, 1947) and Forte Apache (John Ford, 1948), the latter two starring John Wayne.

Near the end of her career, Rich also had a major supporting role in the jazz movie New Orleans (Arthur Lubin, 1947) featuring many legendary jazz performers, including Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday.

Rich’s final film appearance was in a small role in Ingrid Bergman’s Joan of Arc (Victor Fleming, 1948) in Walter Wanger’s lavish production with an enormous cast. Thereafter, she spent the rest of her long life in retirement, growing avocados.

A retired old lady remembers

In 1985, John Kobal interviewed a 95-year old Irene Rich about her film career, which was published in the journal Films and Filming in January 1986. Here, she recalled that she was ‘never a girl’ in the movies, usually playing ‘sophisticated, sad and worldly women.’ She describes joining the film industry in 1918 as a 27-year old who ‘had never even been in a school play’ and yet was ‘never without a job’ between 1918 and 1945. She vividly recalls being directed by Lubitsch during the making of Lady Windermere’s Fan in 1925 and how he mostly let her do her own thing. She also notes how, after Louella Parsons had predicted that she would fail in talking pictures, she did over 4,800 performances in a vaudeville act to improve her voice. She also describes her former producer Darryl F. Zanuck as a ‘nasty little man’ and her former co-star Monte Blue as a ‘sissy’, while describing Will Rogers as a ‘real gentleman, a fine man, a wonderful person.’ There is little sense of nostalgia for the golden age of Hollywood in her comments but rather that her working conditions were often tough, highly competitive and that not all her colleagues were supportive. In short, she portrays the early American film industry as being no place for a lady and seems to consider herself lucky to have survived unscathed.

The vagaries of memory

When recollecting her Hollywood career, Irene Rich dismissed some men (Zanuck and Blue) and remembered others more fondly (Rogers and Lubitsch), while others went unmentioned (Frank Borage) in the mid-1980s. Similarly, some of Hollywood’s greatest leading ladies of the Teens, Twenties and Thirties have lived on in published histories of Hollywood, while others have disappeared. Ruth Chatterton, Marie Prevost, Louise Fazenda and Irene Rich have been largely lost, possibly to make way for the likes of Ruth Elizabeth (Bette) Davis, Marie Dressler, Louise Brookes and Irene Dunne.

But what did it take for these women to be remembered? Huge success at a pivotal historical moment? An association with a ‘great’ director or a male co-star? A series of acclaimed films that form part of the film canon or are judged to be representative of a particular studio or genre at a certain time? These are certainly reasons why some high achieving performers are remembered rather than others, but not necessarily. Memory is subject to a peculiar set of conditions that means that some people, events, names and faces are remembered rather than others. And history seems just as vague and unpredictable. Why do certain names and faces come to mind more readily than others, and what does this tell us about the person (or people) doing the remembering? The fact that Ruth Chatterton’s voice resonated with me and drew me back to her and her films must surely say something about me. What is it in Marie Prevost’s face that struck me and made an impression, one that has lasted when so many others have faded? What made the name of Louise Fazenda more memorable for me than her co-stars Phyllis Haver or Anne Cornwall? Why, after seeing Lubitsch’s version of Lady Windermere’s Fan did I so vividly recall the images of Irene Rich rather than May McAvoy? And having reached this point, what do you most vividly remember from the above? And do you have any idea why that is?

Be the first to write a comment.