In 2009, my University of Sunderland colleague Susan Smith and I signed a deal with the British Film Institute to develop a series of 40,000 word books on individual film stars. Although it wasn’t part of our original plan, the Commissioning Editor for the series wanted one of us to produce a 60,000 book – which was referred to as the ‘Mother Volume’ – to provide an overview of star studies as a dynamic, long-standing and wide-ranging branch of film studies and I was eventually persuaded to take on the task of trying to chart and make sense of the debates on film stars and stardom that had been circulating across the discipline before and after Richard Dyer published his landmark study Stars for the BFI in 1979. As a project, this was similar to the book Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility that I’d written with John Mercer for Wallflower Press in 2004, although this time I had twice as many words at my disposal to map out the highways and byways of this sub-disciplinary field.

Since Now, Voyager had captured my heart and introduced me to the work of Bette Davis as an undergraduate student in the mid-1980s, I had been fascinated with the Hollywood ‘star system.’ Consequently, I’d been an avid reader of books on stars and stardom. Dyer’s Stars and Heavenly Bodies (1987) had made a deep impression on me, as had Christine Gledhill’s (ed.) Stardom: An Industry of Desire (1991) and Jackie Stacey’s Star Gazing (1994). An increasing interest in film acting had also lead me to the work of Cynthia Baron and her co-written book Reframing Screen Performance (2008) with Sharon Marie Carnicke, as well as several of her essays. These had not only deepened my understanding of how actors produced performances within studio-era Hollywood but also influenced the methodology I used for investigating and analysing them. So writing Star Studies: A Critical Guide enabled me to discuss the value of these studies, while branching out much further to explore a greater range of literature on the subject of stardom, performance and celebrity; all of which provided me with a more comprehensive understanding of the field.

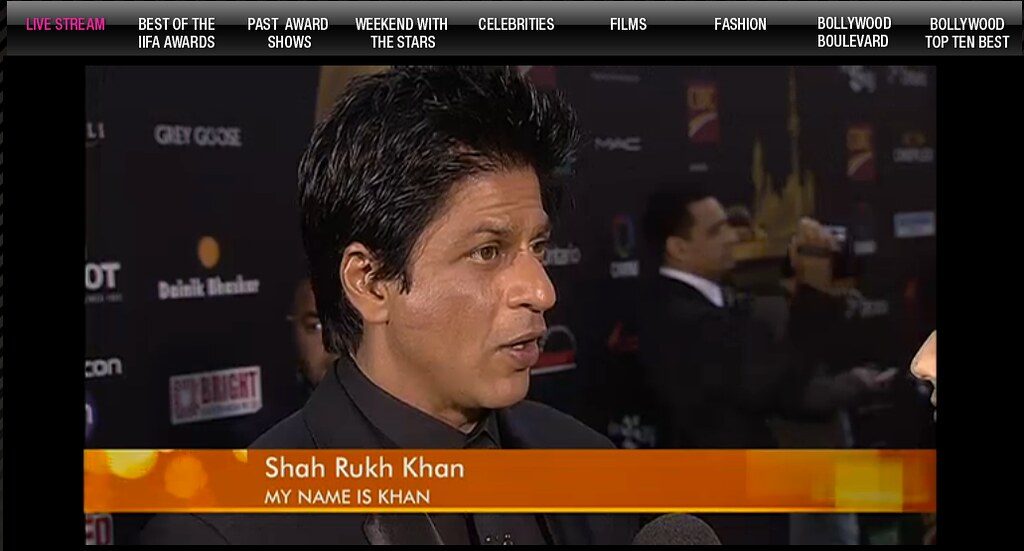

Writing this book also gave me the chance to break out of my comfort zone and explore the stars and star systems of other national cinemas, including those of Britain and several major European countries, as well as China and India. In fact, as soon as I discovered the scale of Bollywood cinema and the extent to which Bollywood stars are worshipped almost like gods around the world, I knew that I needed to devote a considerable proportion of the book to reviewing the research that had been carried out on Indian stars. This led to my discovery of many great and hugely versatile stars such as Nargis, Amitabh Bachchan, Amir Kahn, Madhuri Dixit, Shahrukh Kahn and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan. This opened up a fascinating new area for me and, although I felt like I was skating on thin ice when discussing these and other major Bollywood stars given my lack of familiarity, I decided to take a chance and use what limited knowledge I had to create a Hollywood-Bollywood comparison as a thread running throughout the book.

It was for this reason that I decided to put Aishwarya Rai on the cover of the book, using a publicity still from one of my favourite movies, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002) starring Shah Rukh Khan, with Madhuri Dixit and Aish Rai battling it out for the leading female role.

In the end, even 60,000 words didn’t really provide enough space to do justice to all the important and interesting studies that had been conducted on stars and stardom in English, with a considerable amount of relevant material being left out of the final version. Hopefully though, there was sufficient here to indicate that star studies was an exciting, important and evolving field within film studies, one that could offer students and scholars of cinema some productive ways of engaging with film, cinema history and various aspects of contemporary film cultures from around the world. My greatest hope for this book was that readers would find it as engaging and thought-provoking as the writing of it had been for me.

Blurb on the back cover:

Star Studies: A Critical Guide provides a lively introduction to the major approaches and key developments within this key area of film studies. It identifies a number of dominant themes, explains major theories, concepts and methodologies, and explores the diversity of approaches that have helped shape the international study of stars and stardom.

Comparing the stars and star systems of Hollywood, Bollywood, China and many European countries, from the early-twentieth to the first decade of the twenty-first century, Martin Shingler considers the multiple functions of stars: as an elite workforce within the film industry, as actors and performers, as role models and cultural representatives, as icons and images, as transnational and national symbols, and as commodities.

The scope of star studies is wide, historically and geographically, but this book helpfully focuses on the salient features of the discipline, providing a cogent overview of star studies, while suggesting some useful avenues for further research.

Some extracts:

… film stars are used in different ways by different kinds of people the world over. As objects of beauty and physical perfection or as imperfect human specimens, they provide pleasure, sometimes provoking humour, sometimes admiration and fascination. As icons, stars secure funding and distribution deals for film-makers. They also undertake promotional work, generating public interest and media attention, ensuring the successful release of their films. As a source of gossip and speculation, they support a global media network of newspapers, magazines, broadcasting and the internet, while also raising questions about individuality, personhood, relationships, personal ambitions and desires. In short, they make a profound contribution not only to the film industry but also to the experience of life itself, attracting high levels of attention from the general public, journalists, media commentators, theorists and historians. Therefore, the questions ‘What is a star?’ and ‘What do stars do?’ become fundamental ones. [page 3]

Star studies has developed over a significant period of time and taken numerous forms, so long and so various that it has become necessary for a book that maps the existing field of academic enquiry and considers what lies just beyond the known borders of the territory. This branch of film studies has also produced numerous star theorists and their work can be used as coordinates when mapping out the different areas of star studies. The work of these high-profile theorists deserves to be appreciated as significant scholarly achievement that has had a profound influence within the wider domains of media and cultural studies. Such theorists are not beyond criticism, of course, and nothing is to be gained by ignoring the valuable critiques that have been made in response to them: that is, such criticism enables us to refine, extend and diversify our enquiry into film stars and stardom. In delineating the terrain covered by star studies, this book offers a wide-ranging perspective and yet it is not without omissions and oversights. Where there is knowledge there is also ignorance and, therefore, while some areas are comprehensively covered here, others are under-represented or even neglected entire (e.g., child stars). Readers are invited to fill in such gaps with their own research, to actively respond to what is missing and further the debate. [page 4]

Film stars attract attention. They also play a seminal role in the production and marketing of movies, often accounting for a large proportion of film’s budget. Stars are used to secure funding for films due to the belief that they make a significant contribution to the potential profitability of movies in an otherwise unpredictable market. Many films are produced as ‘star vehicles’, showcasing the star’s talent, capitalising on both their acting skills and their public persona. Stars are so vital to the overall operation and success of the film industry that their popularity is closely and systematically monitored. ‘Bankable’ stars are highly sought after and excessively well remunerated. Many of the world’s top stars have a large international fan-base, while most of the major film-making countries have produced stars of international standing. Some stars have been used to represent national characteristics within the global economy of the mass media, their fame extending well beyond the confines of the cinema via newspaper and magazine journalism, the internet, and television and radio appearances. [page 8]

Many film actors become stars following a ‘breakthrough’ role in which their performance attracts the attention of film critics, receives rave reviews and is subsequently nominated for a major film award. On the back of this, they often gain a higher public profile, attain star status (with leading roles, top billing and star vehicles) and sometimes acquire a recognisable and distinctive (often imitable) signature style: that is, an idiosyncratic set of gestures, movements, poses and expressions that become a major part of their trademark. [page 37]

Although this is not the only route to film stardom, it is the classic one. Consequently, many stars, agents and managers take acting seriously. Stars go to great lengths to extend and improve their acting skills, while their publicists ensure that attention is drawn to their achievements. Critics and journalists pay close attention to star performances, charting their highs and lows, comparing one performance with another, either from an earlier film or by another actor in the same film. Film performances are scrutinised, interpreted and evaluated, repeatedly and in detail, by different kinds of people from all over the world: audiences, fans, buffs, newspaper critics, industry analysts and trade journalists, magazine feature writers, interviewers, gossip columnists, internet bloggers, celebrity reporters, film scholars and media students. [page 37]

The nature of star quality has long been a feature of much writing about stardom: in other words, those qualities that are most commonly associated with stardom or even considered prerequisites. While these qualities are necessarily subject to change over time and may vary in different national or cultural contexts, some qualities are commonly considered necessary for a star to achieve success: most notably, charisma, expressivity, photogenic looks, mellifluous voices, attractive bodies, fashion sense and style. Of course, there are inevitably exceptions to the rule: that is, stars that rise to the very pinnacle of stardom without possessing one or even a number of these. [pages 65-65]

Versatility is a feature of star acting, particularly in the post-studio era. Although stars are often considered to play themselves in each and every role, being associated with a particular type, a specific genre and a recognisable set of mannerisms, the reality is that most stars since the 1960s have been required to work for different production companies, with a variety of directors and crew, often in different countries and across a range of genres and media in order to maintain their star profile. [page 89]

Stardom has been a dominant feature not just of Hollywood but of film industries around the world and, as such, can be considered in terms of the mechanics of the star system, including the way stars are discovered, developed, deployed, presented and evaluated within the film industry. The system is characterised by star and studio associations (e.g., Garbo and MGM, James Cagney and Warner Bros., Shah Rukh Kahn and Yash Raj Films), the production of star vehicles (e.g., the Charlie Chaplin film, the Gracie Fields film, the Arnold Schwarzenegger film), often associating certain stars with specific genres (John Wayne and Westerns, Gene Kelly and musicals, Boris Karloff and horror movies) or developing actor pairings (Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, Nargis and Raj Kapoor, Rock Hudson and Doris Day). The system also entails actor-director pairings (Rock Hudson and Douglas Sirk, Amitabh Bachchan and Hrishikesh Mukerjee, Robert de Nero and Martin Scorsese, Johnny Depp and Tim Burton. [pages 92-93]

The role of agencies, such as ICM (International Creative Management), in packaging talent (most notably, stars, writers and directors) is crucial here, with these associations and collaborations operating within economic and legal frameworks. Contracts determine a star’s conditions of service with a studio, their levels of autonomy and control. Within this system, some stars have prospered, even becoming the directors and producers of their own films (e.g., Woody Allen, Jody Foster and Amitabh Bachchan).

Stars are differentiated from other film actors by the level of attention given to them in terms of marketing, promotion and critical reception, but also in the level off renumeration they receive. Stars are not only a category of labour but also a form of capital, constituting a significant investment. An actor’s star status ultimately rests upon their proven popularity with large numbers of moviegoers and the extent to which that sizeable audience can be predicted to attend a movie in which the star appears. On that basis, a star can command a high salary, which is justified by the probability that audiences will pay to see their films. [page 95]

In order to retain control and ownership of their talent, studios employed stars on contracts that could last for seven years, with an annual or biannual option to release the star if they were no longer viable. The star, on the other hand, did not have the option of leaving the studio until the full term of the contract had expired unless the studio decided to release them. As long as they were under contract, the vast majority of Hollywood stars from the late 1920s to the early 60s were legally required to work exclusively for the studio that had contracted them, having no say in the roles in which they were cast nor how their image, voice or performances were used, either in films or promotion and publicity. [page 101]

Just as stars are hired to perform in front of cameras and microphones, they are also contractually obliged to make public appearances and participate in media interviews to promote their films, and a whole genre has emerged within television broadcasting to capitalise on the availability of major film stars. This is the live chat show, most famously hosted in the USA by Steve Allen, Jack Parr, Johnny Carson, Jay Leno and David Letterman. [page 141]

Although a star will invariably enact and maintain their established public persona when making such appearances, these do also provide some opportunity for stars to reveal (and audiences to glimpse) aspects of the ‘real person’ or, at least, they promise this opportunity even when it is seldom granted. [page 141]

It is the lot of the sex symbol to be loved and loathed, worshipped as a sex goddess and ridiculed as a travesty of womanhood. While the rewards can be considerable for the actress who assumes this mantle (i.e. in terms of lucrative employment, fame and popularity), the costs are equally great (i.e. in terms of typecasting, a short shelf-life and a loss of credibility). The excessive nature of the sex symbol makes her not only the ultimate in heterosexual male desire but also a parody of conventional patriarchal ideals of femininity, incorporating some aspect of mockery and critique into her image and performances, accounting for the sex symbol’s longstanding appeal for gay audiences. [page 163]

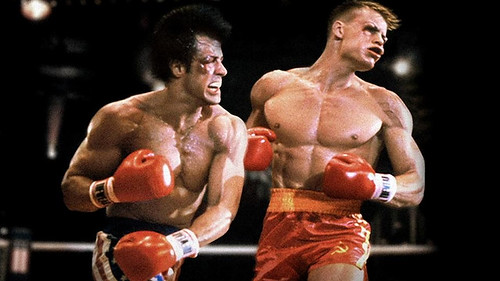

The 1980s and 90s film star body-builder (most notably, Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger) has taken the place of the 1950s sex symbol, his pumped-up and oversized physique replacing the blonde bombshell’s pneumatic body, his spectacular pecks substituting for her ample bosom, his hyper-masculinity matching her ultra-femininity. In so doing, the body-built action star has elicited a similar degree of ambivalence among audience and critics, being both admired and ridiculed. [page 164]

Stars exist primarily in the realm of representation and, as such, are divorced from reality. Their relation to reality is necessarily tenuous, given that most inhabit an exalted position in a higher social sphere. On screen they may play characters that are closer to real life, these characters having been designed by writers to represent and articulate aspects of human experience. However, social disconnection is often the price of fame, the celebrity eliciting unusual responses from most of the ordinary people they encounter in daily life. [page 177]

Film stars, the ultimate celebrities, can easily become detached from the real people and the culture that they are generally believed to represent, so that to read them as representative is to ignore the gap that separates stars from ordinary people. Once raised to the lofty heights of stardom (the upper stratosphere in the case of super- or mega-stars), the culture from which the star emerged becomes insignificant. To ignore the pedestal on which stars are raised is to ignore the gap that separates them from their fans, the gap that generates desire for the star, the desire to be like their favourite star as well as the desire to know more about them. [page 177]

Though chose-ups, films provide intimate views of stars, while interviews in magazines offer intimate insights into their personalities and private lives, for which many people will pay a modest sum. Yet despite these repeated incursions into their personal space, stars remain distant and out of reach. Stars, therefore, both invite and evade scrutiny. [page 181]

What is clear is that there is no one way to produce a star study, with a variety of alternative methodologies and conceptual frameworks being available to those in pursuit of answers to the questions posed by stars and stardom. Studies involving detailed textual analysis of star acting have as much to contribute to the expanding field of star studies as detailed analysis of a star’s reception in fan magazines and newspaper reviews. [page 184]

Studies informed by interviews with stars, their acting coaches, managers, agents and PR staff, have as much to reveal as others that chart career trajectories through popularity polls, box-office receipts, star ratings, awards and accolades. Studies that involve interviews with focus groups and questionnaire surveys completed by representative groups of fans offer just as much as others that explore how stars are used as icons, figureheads for countries and organisations, commercial companies and products. [page 184]

Any one of these approaches to exploring stars and stardom will elicit valuable material that enables us to glimpse something of the multiple forms and uses of stars and stardom in operation throughout the world’s film industries, cinema cultures and mass media, as well as in society more generally. In short, there is no recipe for the perfect star study. Moreover, star studies as a discrete branch of film studies has more to gain from plurality than from a single orthodox approach. [pages 185-185]

Copies of Star Studies: A Critical Guide (2012), including an eBook, can be purchased here: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/star-studies-9781844574902/

New and used copies of the book can also be purchased from Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Star-Studies-Critical-Guide-Stars/dp/1844574903

Be the first to write a comment.