“Are you looking at me!”, she seems to be saying with a certain degree of insolence. “Go on then, look all you like. I guess that’s what I’m here for, to be looked at by people like you. Feast your eyes on my baby-doll good looks, my shapely figure and glamorous hair. But forgive me if I look back at you, if I match your gaze with my own stare. I can see too, you know. Oh I see lots of things in this business! You’d be surprised what I’ve seen. And I’m prepared to talk about it too. Shall I talk about you and tell you what I see? What you look like to me? Or would you prefer me to keep quiet. Hold my tongue. Play the dumb blonde? Just like all the rest, I guess. Well, I’m sorry, but there’s nothing dumb about me!”

I can only imagine what’s going on in her head when this photograph was taken. Maybe it went something like this? “Still looking at me, I see. And after all this time. Well I’m here to be looked at, everything calculated to attract your gaze. And there’s so much more to see now, isn’t there? A few extra pounds and more lines, and a lot more experience. You might not like it. But, then again, you might. To be honest, I’m tired of it all but it’s what I do, what I am. More brassy than classy, they say, and yet I’m still more sassy than dumb. I have to keep my wits about me these days, use all the tricks of the trade to go on, if I want to work and still be ‘Diana Dors’. And I do, however tough that might be. That’s me. Not for much longer perhaps. So while I’m still around, go on and take a good long look. I’ve nothing to hide. Don’t be intimidated. I won’t bite. Well, I might.”

Introducing Diana

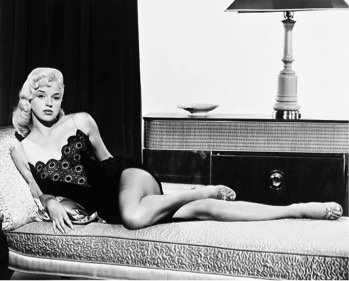

During the 1950s, Diana Dors (1931-84) became Britain’s most successful sex bomb, being the only British blonde bombshell to be able to hold her own against the likes of Hollywood’s Marilyn Monroe and France’s Brigitte Bardot. From the 1950s to her death in 1984, Dors sustained a high-profile career in Britain despite frequent reports of scandal in the tabloid press and the loss of her hour-glass figure.

When it became harder for Dors to secure film work in the 1960s, she turned to television, theatre and live cabaret, making regular appearances on TV chat shows and panel games. She also published a series of memoirs and appeared regularly in magazines. In other words, Diana Dors was as much a celebrity as a film star, as adept at manipulating media interest in her as she was at performing in front of film cameras and microphones.

Diana Dors was a major film star for a brief period in the mid to late fifties, with Yield to the Night (J. Lee Thompson, 1956) being her most critically acclaimed film. This was nominated for a BAFTA award and a Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1956, and it earned Dors a three-picture deal in Hollywood with RKO. Her Hollywood star vehicle The Unholy Wife (John Farrow, 1957), in which she appeared opposite Method actor Rod Steiger, failed to take America by storm and Dors returned to Britain shortly after making it and long before it was released. It was clear by 1960 that her film star status was waning and she was forced thereafter to take supporting roles and eventually character parts – often little more than cameo appearances – in order to continue working in the film industry.

Although Dors’ time as a fully-fledged movie star was short-lived, her film career actually spanned thirty-seven years, during which time she made a total of 67 films. Having made her screen debut at the age of 15 in 1946, she appeared in her final film at the age of 52 in 1984. Between 1946 and 1984, she proved herself adept at supporting and starring roles, character and glamour parts, playing comedy and serious drama. She even ran the gamut from children’s fantasy films, soft-core porn, adventure movies, horror films, romantic comedies, Westerns, social problem films and melodrama. Occasionally she played opposite some major Hollywood stars, like Victor Mature, Joan Crawford and Jack Palance. She also worked with some important and influential directors, such as David Lean, Maurice Elvey, J. Lee Thompson, Carol Reed, Jack Cardiff, Jacques Demy and Joseph Losey. Yet her image as a ‘sex symbol’ and her propensity to attract media attention (both wanted and unwanted publicity) meant that her work and talent as a film actor was largely overshadowed. I’d like to put that right.

Early Dors

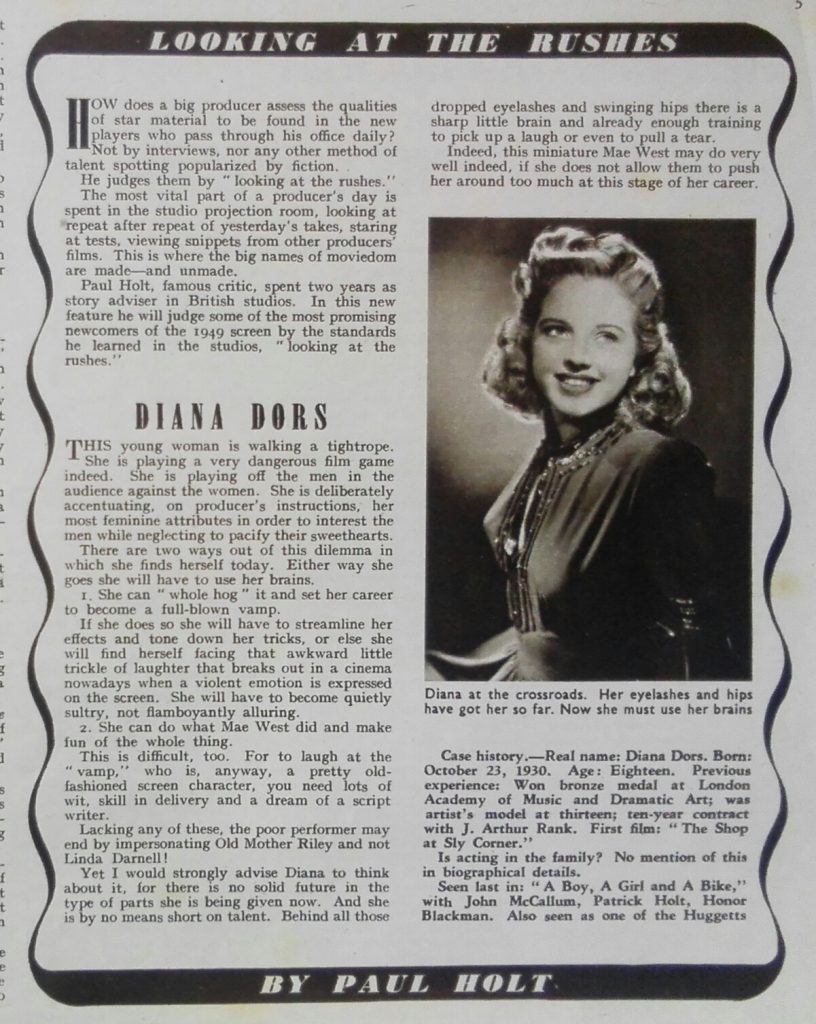

First and foremost, Diana Dors was an actor. She was trained at LAMDA (London Academy of Music & Dramatic Art) in 1946 and then secured a contract with the Rank Organization in 1947, where she completed her training at their famous Charm School. As an actor, Dors performed on stage, in film and in television, performing both serious drama and comedy, mainly in Britain, occasionally in Hollywood and Europe. Even as a teenager, her acting talent was recognised. During the late 1940s and early ‘50s, between the ages of 15 and 19, she secured a steady stream of small roles in British films.

At this formative stage of her career, critics like Paul Holt were quick to note Dors’ talent and intelligence but also the danger she ran in being cast in vamp roles and by being given the glamour treatment, as this was likely to result in a short shelf life as well as a limited range of roles.

By 1950, Dors had graduated to major supporting roles in such films as Diamond City (David MacDonald, 1950), My Wife’s Lodger (Maurice Elvey, 1952), Is Your Honeymoon Really Necessary? (Elvey, 1953) and The Weak and the Wicked (J. Lee Thompson, 1954). Here and elsewhere, Dors was immediately recognisable as a type, the ‘Glamour Girl’, which she had been playing fairly consistently since her debut in The Shop on Sly Corner (George King, 1947).

A British blonde abroad

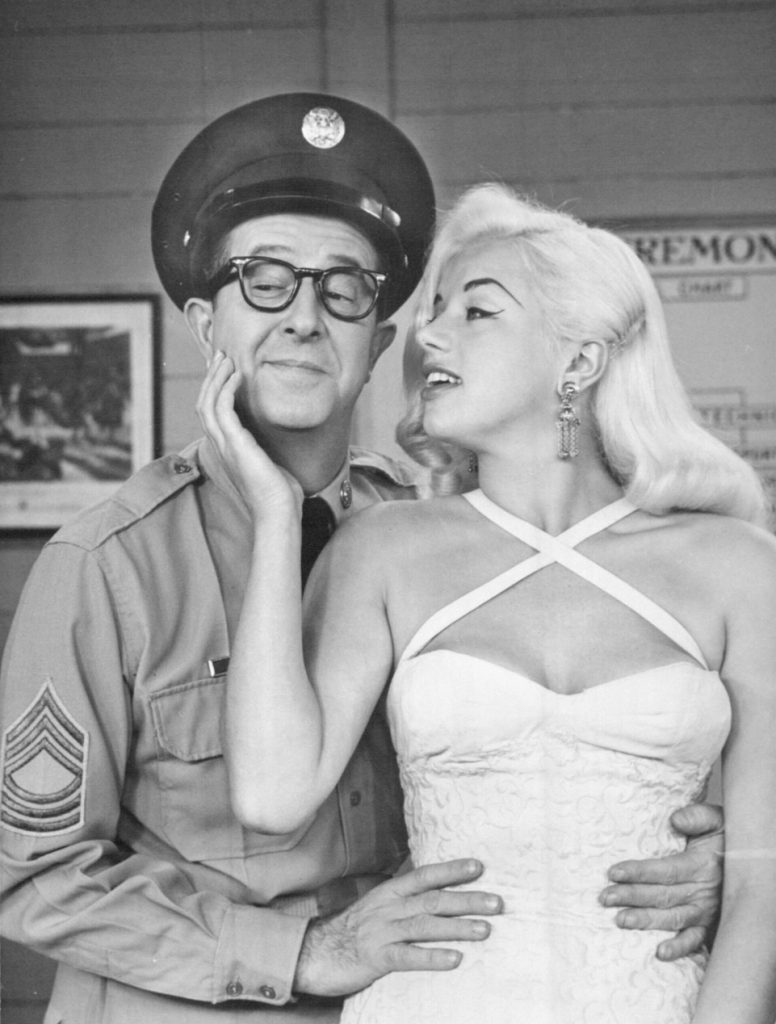

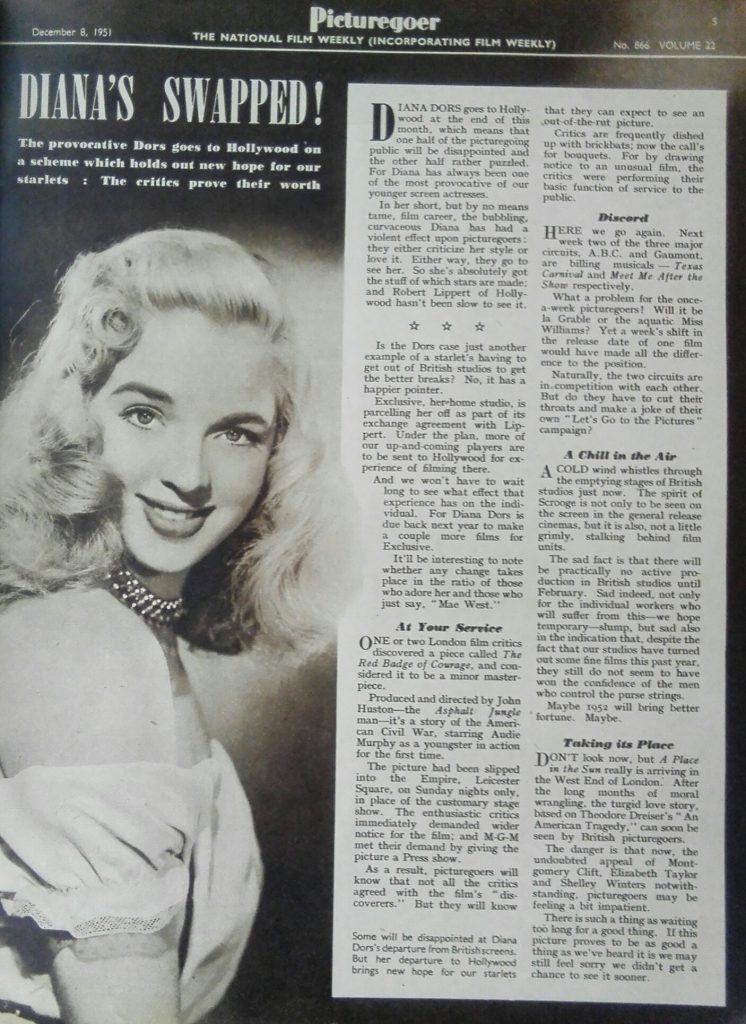

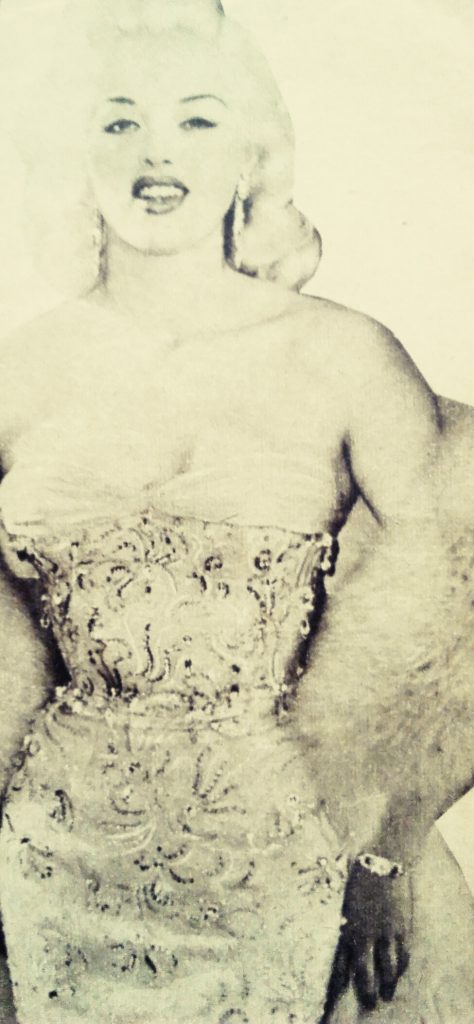

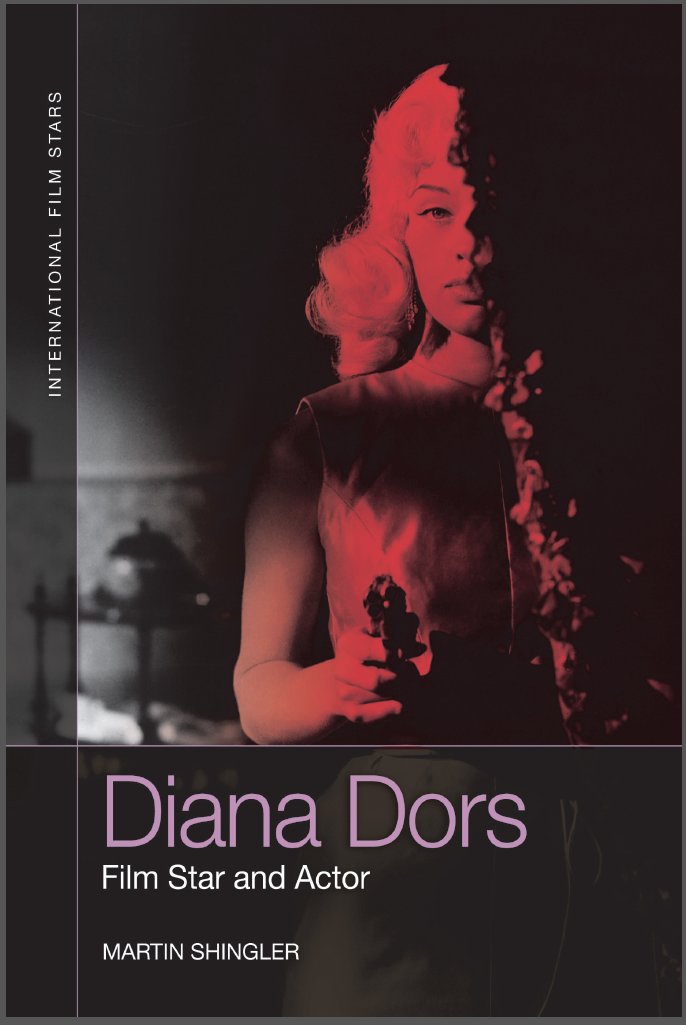

As this image reveals, Dors was not only glamorous by the end of 1951 but also a blonde. Aged 21, she had acquired Hollywood film star looks even if her films didn’t have the budgets and production values of Hollywood movies at this time. Dors’ new image suggested that she wouldn’t be staying in Britain for long and that had her sights were firmly set on Los Angeles.

By this time, the Dors’ type was established as a fashionable, attractive and ambitious girl with a taste for stylish clothes and jewels, dance halls and nightclubs, alcohol and cigarettes, fast cars and fast men, usually mobsters or petty criminals. In her films and private life, she was often just on the wrong side of the law, even though her heart was mostly in the right place. Flirtatious but sulky, her trademark was her pout and her slender legs, which were consistently revealed, noticeably on her entrance into a film. As she most often played small roles with just a few minutes of screen time, she had to make an immediate impression. There was little time for her to establish her character and so with each role she re-presented the same basic persona, one that regular moviegoers would immediately recognise. This way, audiences knew exactly what she signified and where she was coming from.

Since Dors spent the first six years of her film career in minor roles with limited screen time, she became adept at making an immediate impression upon audiences and stealing scenes with her glamour, sexuality and wit. During the early 1950s, it was also clear that Dors was developing other talents besides acting. One of these would propel her from the margins of British cinema to the international spotlight of celebrity.

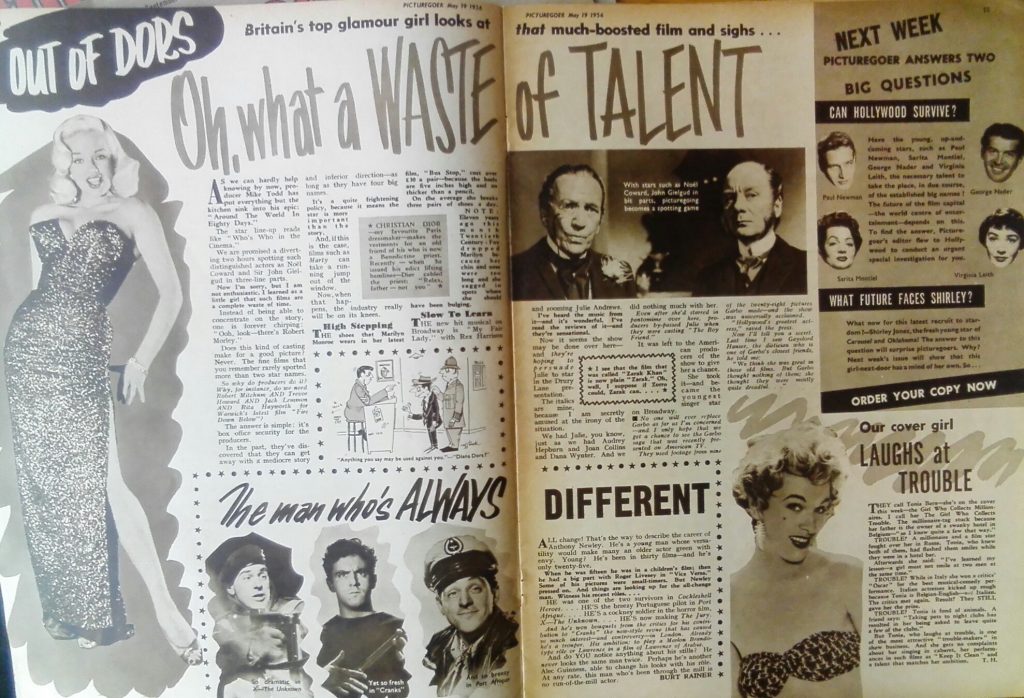

While other British actresses such as Anna Neagle, Celia Johnson and Glynis Johns kept low public profiles, Diana Dors went all out to court attention, particularly from the tabloid press. Considerable media attention has given to the publication of a photographic book called Diana Dors in 3-D in 1954, which was accused of being obscene. Her appearance that year at the Venice Film Festival in a gondola wearing a mink bikini proved to be a highly successful publicity stunt that brought her to international attention. By this time, she was regularly headline news in the British papers, due largely to a series of scandals concerning the criminal activities of her first husband Dennis Hamilton. By the mid-Fifties, Dors was dominating the movie magazines in Britain. Almost every edition of a major film publication featured an article on her during this period and, more often than not, she could be found on the cover.

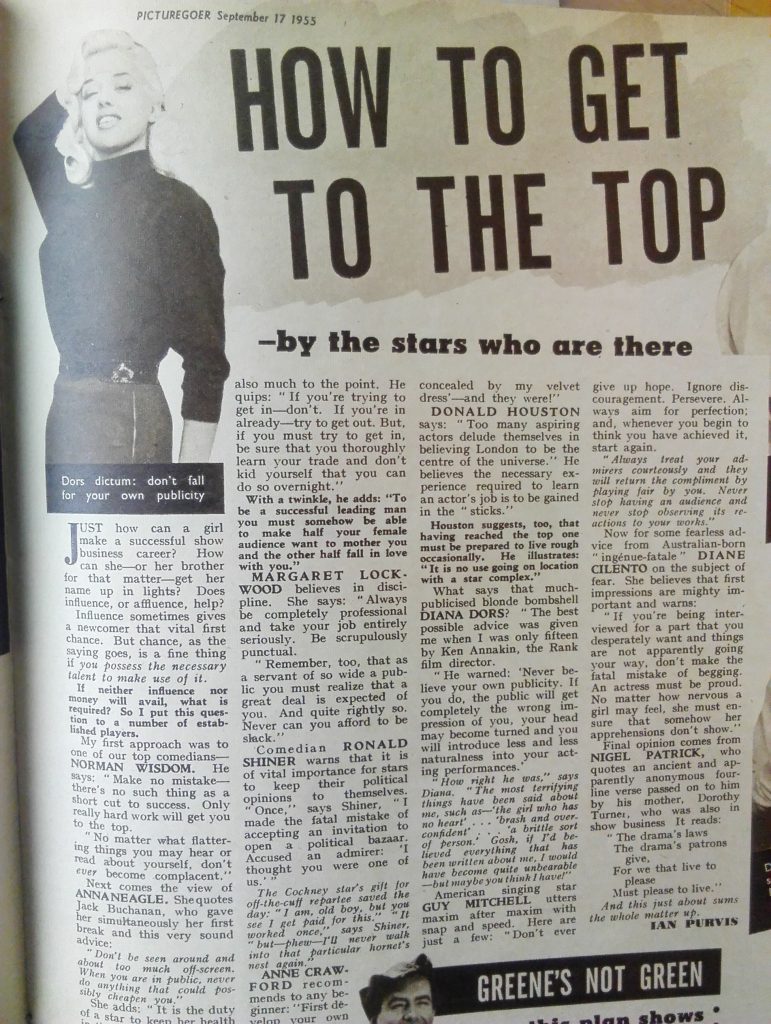

It’s clear from a Picturegoer article published on September 17, 1955 (see image above) that Dors was believed to have reached the top of her profession by the mid-Fifties. Written by Ian Purvis and entitled ‘How to get to the top – by the stars who are there’, Dors was one of a number of major British stars who offered readers advice on how to be successful in show business. Anna Neagle, for instance, advised discretion. “When in public,” she suggested, “never do anything that could possibly cheapen you.” Margaret Lockwood, the ultimate ‘Wicked Lady,’ argued that discipline was what was really needed, adding “always be completely professional”, including being “scrupulously punctual”. “Never can you afford to be slack,” she warned. Dors, however, insisted that the route to success came from never believing in your own publicity. Having been described in the press as heartless, brash and over-confident, Dors noted that she would have become “quite unbearable” had she believed any of these things. The implication here was that publicity was the key to success for a star but that the wrong kind of publicity could be personally damaging if taken to heart. Her rule of thumb was to treat it all with a heavy dose of scepticism.

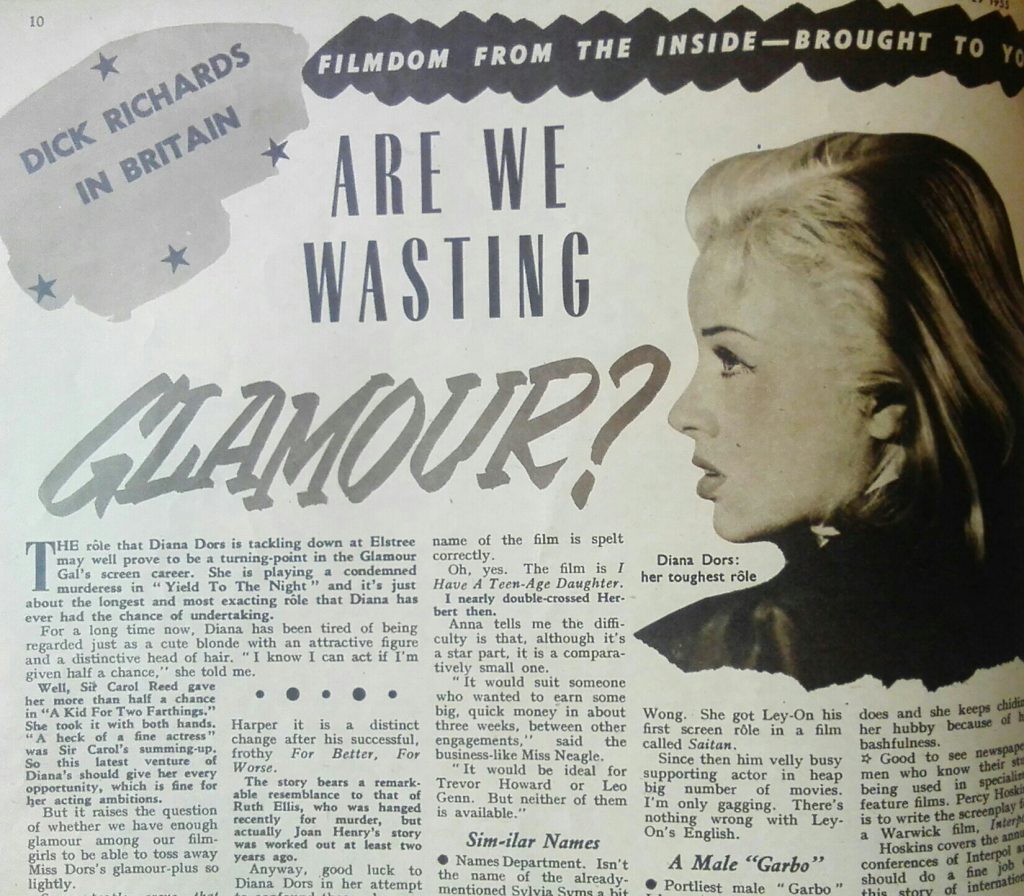

If Dors’ publicity was over-shadowing her work as a screen actress during the early to mid-Fifties, then she briefly transformed this situation in 1956 with a distinguished performance in Yield to the Night, the film being promoted as her breakthrough into serious dramatic acting.

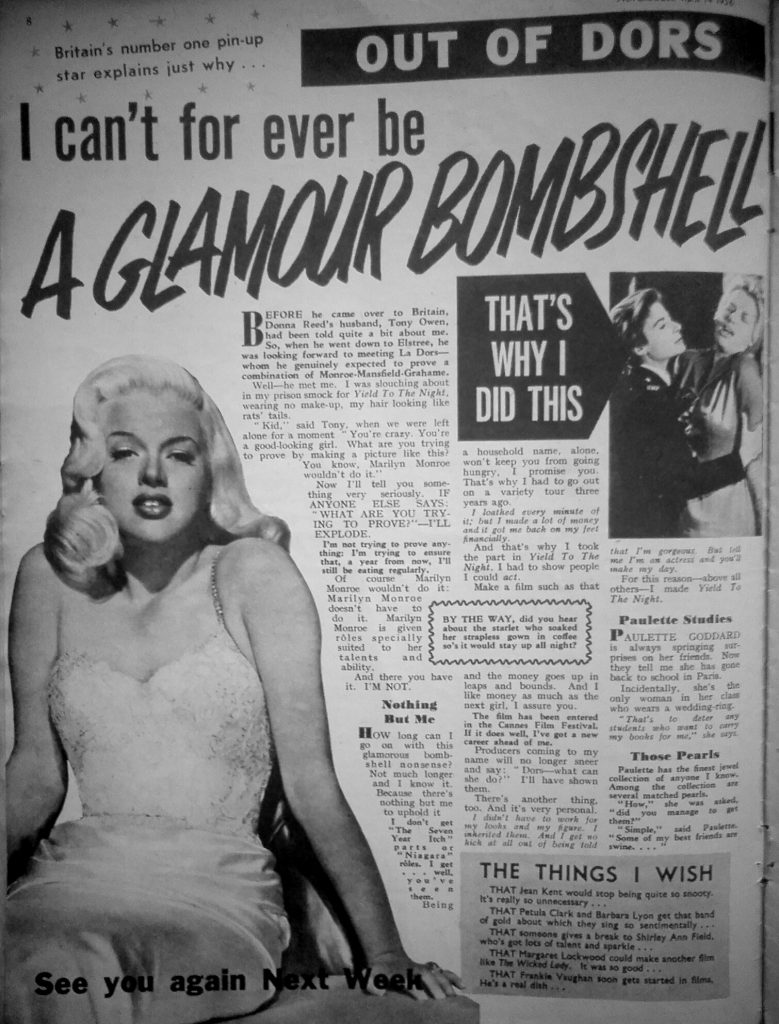

In April 1956, Dors asked the readers of the popular British movie magazine Picturegoer, “How long can I go on with this glamorous bombshell nonsense?” Here, she explained that she’d taken the part of the female prisoner in Yield to the Night to show people that she could act.

Playing a young woman imprisoned and finally executed for murder, Dors was de-glamourised in her prison scenes with the dark roots of her bleached hair showing through. She was also costumed in a shapeless, drab prison uniform. In other words, she was ‘de-glamorized.’ However, her familiar blonde bombshell image appeared in the scenes depicting events prior to her character’s imprisonment, presenting two very different incarnations, the actress and the star. While not all members of the press were prepared to take Dors seriously as a dramatic actor, this award-winning film enabled Dors to showcase her acting credentials. However, for all that, she posed repeatedly in glamorous outfits for international press photographers when promoting the picture at the Cannes film festival.

The sensation she provoked at Cannes brought her to the attention of Hollywood executives and resulted in a three-picture deal with RKO.

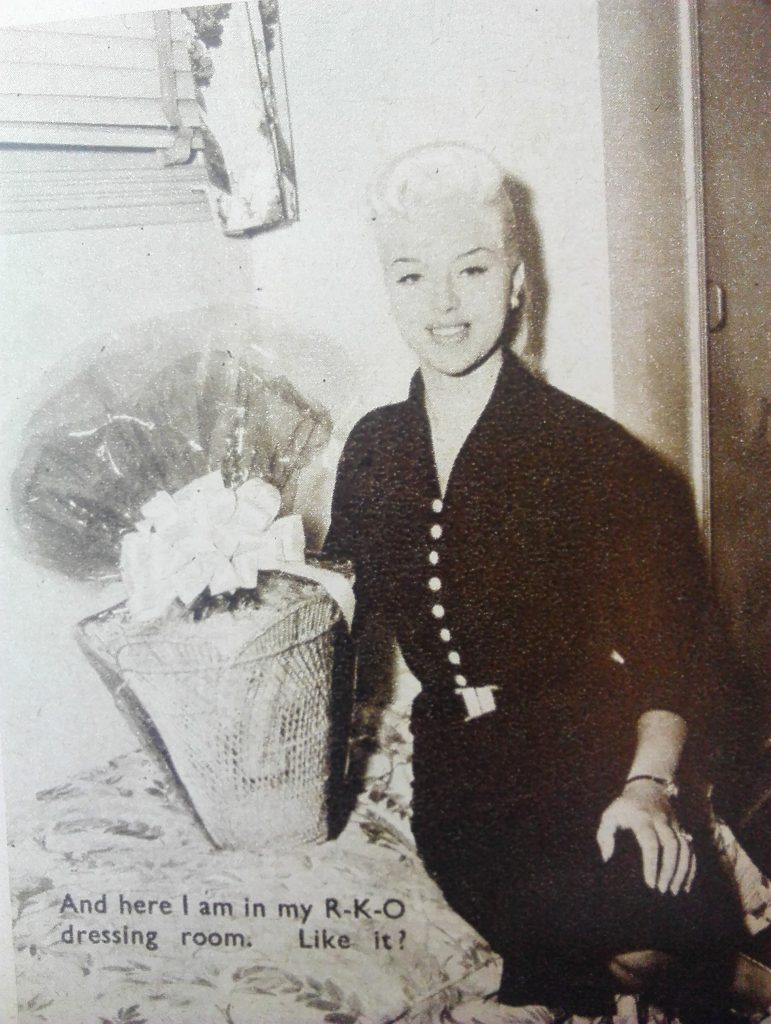

Dors in Hollywood

Diana Dors made two films in Hollywood for RKO during the second half of 1956. I Married a Woman was a romantic comedy starring George Gobel, which began shooting in July. In September, Dors replaced Shelley Winters as Rod Steiger’s co-star in the crime melodrama The Unholy Wife. Both films received poor reviews and failed at the box-office when eventually released. In part, this was due to Dors’ increasingly fraught relationship with the American press, although there are other reasons why these movies failed to impress critics and engage cinema audiences in the late 1950s (as I explain in Chapter 3 of my Dors book). The failure of Dors’ Hollywood ambitions cast a long shadow over the rest of her career and had a pronounced impact on her star image. Nevertheless, this failure actually reveals many of the star’s greatest strengths, notably her courage, confidence and determination to be herself.

European Stardom

While the public relations disaster that unfolded in the USA damaged her prospects in the American film industry in the latter part of 1956, this did not immediately impair Diana Dors’ stardom in Britain and Europe, where she continued to gain leading roles and star billing. Indeed, the Italian producer Maleno Malenotti created the perfect star vehicle for her in 1957. This was a lavish widescreen romantic comedy in colour that showcased both the British star’s beauty and the scenic highlights of Tuscany, notably in and around Siena and Pisa, while telling the story of how a young Texan woman called Diana Dixon (Dors) becomes the only female to participate in Siena’s traditional bareback horserace around the Piazzo del Campo after winning a car, a wardrobe of clothes and sufficient funds to live like a princess in Italy for a week. By the end of La Ragazza del palio/The girl of the palio, Dors’ character has not only won the horserace but also the hand of a handsome but impoverished nobleman, Prince Piero di Montalcino, played by the handsome and talented Vittorio Gassman.

After returning from her aborted Hollywood career, Dors reclaimed her crown has Britain’s No. 1 Glamour Girl with leading roles in The Long Haul (Hughes 1957), Tread Softly Stranger (Parry 1958) and Passport to Shame (Rakoff 1959). Injecting a heavy dose of sex and glamour into these, she traded on her glamorous persona, while proving that no one played a ‘tart’ quite like Dors. Although not considered distinguished movies at the time, they showcased her acting skills along with her shapely figure, while also revealing the different types of good-time girl that she was adept at creating: the good, the bad and the extraordinary.

The Long Haul was originally intended as a star vehicle for the American actor Robert Mitchum but was later adapted for his colleague Victor Mature. Dors was cast as the lead female Lynn, the glamorous girlfriend of a crooked owner of a Glaswegian haulage company. She is essentially a ‘tart with a heart,’ abused by her boyfriend and in need of protection from Mature’s character, a tough but thoroughly decent bloke – the strong and silent type.

During a key scene in a roadside café, Lynn tells Harry (Mature) about her sad little life. Tired of being a Glamour Girl, she seeks sympathy from him as the two gaze into each other’s eyes across the table, not with desire but understanding, forging a connection. Mature is attentive and largely static as Dors performs the lines that establish the basic details of Lynn’s backstory. It’s true that she places a hand over his at the end of their conversation, when thanking him for being ‘sympatico.’ However, this isn’t the hand of a femme fatale but rather someone who is tentatively reaching out to a man for protection having been brutalised by men in the past. Yet the actress doesn’t make this wayward woman seem pathetic either. However desperate she might be to find someone to cling to, she’s neither simpering nor childlike. Dors paints a sensitive and complex portrait of Lynn in The Long Haul, depicting her as a woman who, despite being a victim of male abuse, retains sufficient confidence to take the upper hand with a man of Victor Mature’s stature. It’s Lynn that makes the first move, confiding in Harry, appreciating him without flattering him and initiating sexual congress. Taking her time with every line, while mostly averting her gaze and avoiding any obvious batting of eyelashes, Dors invests her character with goodness and intelligence rather than play her as weak, silly or manipulative.

Surviving the Sixties

Shortly after being nominated for three Oscars for The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), the writer-director Ken Hughes expressed interest in making a movie based on Diana’s Swingin’ Dors memoir to be called ‘The Diana Dors Story’. Had this come off it would have given the 30-year old actress the chance to retire gracefully from the cinematic spotlight and spend the rest of her life living in style in Los Angeles with her husband Dickie Dawson and two boys (Mark and Gary). Yet Dors’ life took a different turn, one that saw her touring the world with her own stage show in between making television programmes and movies, before leaving her husband and children in California to pursue her acting career on stage and screen.

Returning to Britain in 1965, Dors was confronted by an unreceptive press as well as a lack of work despite the fact that a large injection of American finance had re-stimulated the British film industry. Dors’ glamorous persona as an icon of unapologetic conspicuous consumption was now totally out of step with the youth-oriented popular culture of the Sixties, which was dominated by street fashion (notably, the mini skirt) that made skinny Jean Shrimpton and waif-life Twiggy the feminine icons of the age. Julie Christie was the new cinematic blonde on the block, supplanting the 1950s Blonde Bombshell with a naturalism, low-key sense of style and an underlying sexual confidence that made Dors look like a caricature in a smutty seaside postcard. Consequently, Dors’ film career failed to rejuvenate during the late 1960s, although her performance with Hollywood legend Joan Crawford in Berserk! (O’Connelly 1967) proved to be a highlight (see Chapter 7 of my Dors book for more on this movie).

Dors was at the lowest point of her career when she made this film in 1966. Just ten years after the peak of her stardom and a year after leaving Los Angeles to take her chances as an ageing sex symbol in Britain, the 35-year old was reduced to singing, joking and telling stories against herself in workingmen’s clubs in some of the roughest parts of England. Here, she was confronted by “audiences of men heckling me over pints of beer”, as she later recalled in Dors by Diana (1981: 248).

Diana Dors might well be pitied for her role as the loud-mouthed magician’s assistant Matilda, especially when she’s presented as an over-the-hill sex symbol who can no longer seduce men in the way her characters did ten years earlier. Yet many cult movie aficionados may applaud the actress for the way she gamely forsakes personal dignity in Berserk!. Dors certainly exhibits an awareness of the peculiar demands of exploitation cinema when performing here, seeming to understand that this type of film required her to not only repeatedly humiliate herself but also to broaden her acting while playing with her tongue in her cheek or with a knowing twinkle in her eye.

Salvation in the Seventies

Dors’ film career finally appeared to be over when 1969 passed without any film projects for 38-year old actress. In this year, she signed a contract with Yorkshire TV for her own situation comedy. Queenie’s Castle (1970-72) was written by Keith Waterhouse and ran for three series over the next two years until it was replaced in 1973 by a less successful vehicle called All Our Saturdays (1973). Queenie’s Castle certainly boosted her flagging public profile in Britain but it was her appearance on stage in 1970 with her younger husband Alan Lake that showcased her acting skills. Dors received rave reviews for her role as a lusty matriarch in Donald Howarth’s comedy Three Months Gone at the Royal Court Theatre in London, which quickly sold-out. After moving to the Duchess Theatre in the West End, this reaffirmed the bankability of her name when playing to capacity crowds.

After turning forty, Dors bucked the trend that rendered mid-life female movie stars redundant. Over the next few years, she played a range of characters in films such as The Amazing Mr Blunden (Jeffries 1973) and Steptoe and Son Ride Again (Sykes 1973). This included some rather extraordinary housewives, from battle-axe harridans to sex-starved cougars preying on younger males in films such as The Pied Piper (Demy 1972).

Based on the famous Grimm Brothers’ folktale of 1816, Jacques Demy’s The Pied Piper provided a small role for Diana Dors that showcased her virtuosic acting skills. The 40-year old actress was billed as a ‘Guest Star’ when playing the Burgermeister’s buxom, bossy and bad-tempered wife. She makes a big impression here as Frau Poppendick in some highly theatrical costumes, the actress deftly conveying her character’s marital and maternal failings in just six short scenes. Although depicting her as an archetypal fairy-tale villainess, she draws heavily upon her own public image and screen persona, which was necessary given the brevity and scarcity of her scenes (see Chapter 8 of my Dors book for more on this film).

Although the 1970s were lean years for the British economy, for Dors they provided an abundance of movie roles, her output increasing from 3 films in 1972 to 5 films in 1975. She found gainful employment in horror movies, with small roles in Vincent Price’s Theatre of Blood (Hickox 1973), Peter Cushing’s Nothing But the Night (Sasdy 1973) and From Beyond the Grave (1974), as well as Jack Palance’s Craze/The Infernal Doll (Francis 1974). Yet it was her appearance in a series of soft-core sex films and smutty sex comedies that led to the revival of her stardom in the Seventies. The star was given top billing in 1972 (for the first time since 1959) by the producer Vernon Becker for her role as the brothel madam and mistress of ceremonies at Maison Margareta in Swedish Wildcats. This low-budget soft-core porn film, directed by Joe Sarno, featured copious amounts of bare flesh, fetish gear, sadomasochism and kitsch cabaret.

In 1975, Diana Dors’ highly sexualised image was exploited in the sex comedies The Amorous Milkman (Nesbitt), Bedtime with Rosie (Rilla), Three for All (Campbell) and Adventures of a Taxi Driver (Long). The following year, she was given top billing for her supporting role in the female-authored Edwardian sex comedy Keep It Up Downstairs (1976). For this, screenwriter and producer Hazel Adair – who had previously created the BBC TV series Compact (1962-1965) and the longer running ITV drama serial Crossroads (1964-88) – re-imagined life in an English country house to allow masters and servants to both live happily together and have sex with each other regularly throughout the day.

Keep It Up Downstairs is a rarity in not only being female authored and produced but also in permitting Dors’ character to be sexual without condemning her as a ‘tart,’ a ‘slut’ or by any other derogatory and misogynistic label. Nor is she punished at the end for being overtly sexual, desiring and promiscuous. In fact, the ending of this film proves to be one of the most satisfactory for any of Dors’ film characters. Not only does her Daisy remain happily married to a millionaire but she also seduces the butler Percy Hampton (Neil Hallett) in the final scene when he arrives at her bedside with breakfast on a tray.

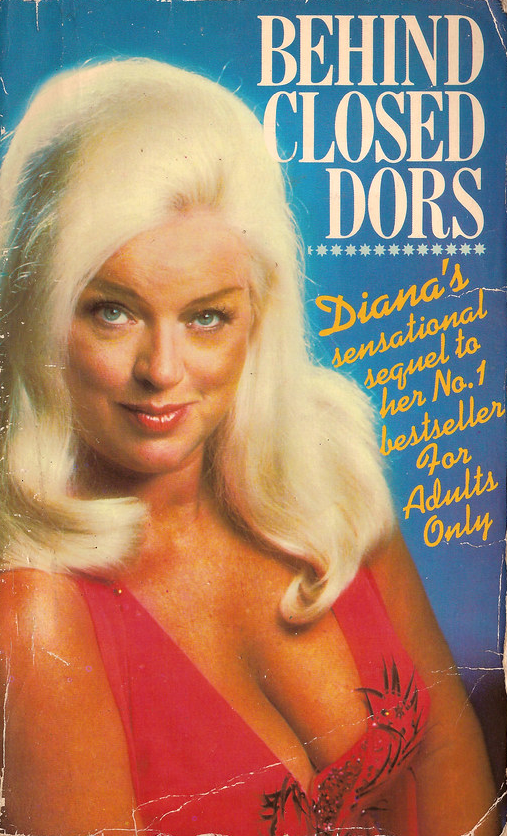

After her starring role and happy ending in Keep It Up Downstairs, Dors made just two more films in the 1970s, Adventures of a Private Eye (Long 1977) and Confessions from the David Galaxy Affair (Roe 1979), dividing her time mostly between television work and publishing autobiographical books. The latter were cheap paperbacks, full of salacious details and bitchy remarks about co-stars, which exposed many of the more sordid aspects of her life. Priced at 95 pence, these were mostly compilations of anecdotes and opinions using an A to Z format that Dors found easy to write and which sold well with suggestive titles such as For Adults Only (1978) and Behind Closed Dors (1979), which was described on the back cover as a “racy collection of gossip, hard facts and bawdy reminiscence.”

An Eighties Icon and National Treasure

Despite declaring in the foreword to For Adults Only that she had no intention of writing her autobiography until she was eighty in 2011, Dors published her life story under the title Dors by Diana in 1981. This £1.60 Futura paperback was presented as the “first, full story she has ever written of her extraordinary life.” Back cover blurb described “how, with fame and the luxury of Hollywood stardom, came heartbreak and tragedy – the turbulent marriages, the bitter-sweet love affairs, the broken promises and terrible betrayals”, clearly situating Dors’ personal history within the realms of popular women’s romantic fiction.

In 1980, Dors performed in four separate TV productions, most notably as the supreme leader of Britain’s female militia that subjugates men by forcing them into domestic servitude as floral-frock wearing minions in ‘The Worm That Turned’ segments of The Two Ronnies comedy sketch show (see above). In addition to this, she also appeared in an adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starring David Hemmings, an episode of Hammer House of Horror (‘Children of the Full Moon’ with Christopher Cazenova), as well as the detective drama series Shoestring (starring Trevor Eve). Switching between comedy and drama, historical fantasy and contemporary realism, Dors displayed her flexibility and acting range to millions of viewers watching these top-rated TV shows.

The following year, the esteemed theatre director, drama critic and polymath Jonathan Miller cast Dors in a small role as the prostitute Timandra in his television production of William Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens (1981) starring Jonathan Pryce. Three years later, she was cast alongside the much admired and highly acclaimed actress Vanessa Redgrave in Joseph Losey’s film version of Nell Dunn’s award-winning feminist play Steaming, which brought her decisively into the feminist fold within months of her death.

Cast in a pivotal role, Diana Dors produced a performance for Joseph Losey that involved glamour and gravitas in equal measure, utilising her famous star image, trademark gestures and understated naturalism with a great deal of poise. From the opening to the closing shots, she quietly wove her way through the film, helping to unite a heterogeneous group of women played by very different kinds of actress. In her curiously central yet peripheral role, Dors was able to utilise her glamorous star image, reveal her strengths as an actor and draw directly on a lifetime’s experience as a woman (see Chapter 9 of my Dors book for more details).

Diana Dors died in May 1984, before the release of Steaming. By this time, she had acquired ‘national treasure’ status, partly because all kinds of people liked her, identified with and admired her – women and men, young and old, gay and straight. Yet this also involved a belated recognition that she was a woman whose intelligence and talent deserved to be taken seriously despite her persistent adoption of an excessively glamorous and overly sexualised femininity. Dors’ combination of talent and industriousness, confidence and honesty, versatility and longevity, intelligence and wit, along with her stoicism and strength, made her a rare figure within the history of British entertainment, one whose stature could not be diminished by the paucity of her film roles.

Dors and I

A spectacularly audacious and voluptuous 49-year old Diana Dors caught my attention when I was a shy and skinny 15-year old. She first fascinated me in 1980 as the ball-breaking Commander wearing a camp military uniform in The Two Ronnies, simultaneously sexy and scary as the head of a matriarchal state police force. The following year, I was mesmerised by her appearance as a glitzy fairy godmother in the pop music video for Adam and the Ants’ hit single Prince Charming. Here, while Adam Ant repeatedly sang ‘ridicule is nothing to be scared of,’ Dors waved her starry wand in the air and transformed his rags into glad-rags, enabling him to attend the queerest of costume balls.

Now I can see why Diana Dors was so perfectly cast as Adam Ant’s fairy godmother. For her role here is not simply to make his dreams come true but to inspire him to love himself and be proud. In so doing, this pop promo capitalised on Dors’ reputation as a survivor despite disaster and derision, as someone who remained unashamed even when acknowledging personal failings and professional failures. Many people craved this kind of chutzpah in the early Eighties. I certainly did.

Yet I didn’t know then that she’d been a major international sex symbol in the 1950s. Nor did I appreciate her skills as an actress, until I saw her some years later in Yield to the Night. Watching this film, I marvelled at her transformation from a glamorous blonde salesgirl into a plain drab prisoner awaiting execution. Yet what was just as astonishing was the sheer intensity of her performance, notably in scenes with co-star Yvonne Mitchell as the caring guard with whom Dors’ doomed Mary Hilton discovers a close bond of mutual understanding, sympathy and – quite possibly – love. The subtlety, sensitivity and subtext that Dors achieved when performing her scenes with Mitchell began to resonant forcefully with me over time. I could easily see why Yield had become the single lasting testament to Dors’ acting skills. It’s an irrefutable fact that no other movie exploited the precision, power and intelligence of her work as an actor to the same degree. For years, I failed to find anything to match this performance across the star’s catalogue of 67 films and felt increasingly frustrated that producers had failed to provide her with any other vehicles worthy of her talent. It really did seem that Yield was the only film that showcased Dors’ acting prowess.

It was after 2012 that I realised that Dors’ other achievements as a film actor lay in fragments, small and often self-contained moments of a movie in which she performed a minor supporting or guest starring role. Consistently denied her own star vehicles and the opportunity to perform a main protagonist, Dors became an expert in creating star performances out of character parts, making her the mistress of the movie moment. She not only brought great skill and sound judgment to these small roles but also a vivid star image, a set of trademark gestures, an impressive amount of confidence and great poise, which meant that she never had to try too hard to gain audience attention.

I began to think about writing a book on Diana Dors after giving a series of presentations on her between 2012 and 2016, mostly at the Celebrity Studies conferences. These revealed a considerable amount of academic interest in this star beyond Britain, including Australia and the Netherlands. However, it was after reading Melanie Williams’ Females Stars of British Cinema (2017) that I approached Edinburgh University Press with a proposal. EUP’s International Film Star series seemed perfect for my study, giving Dors the chance to circulate more widely beyond British Cinema Studies while enabling me to indicate how she had been operating as an international movie star long before and after she went to Hollywood in 1956.

For details of the above, visit https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-diana-dors.html

Working on this book over the last few years has given me the chance to really scrutinise and think about Dors’ acting across the five decades of her supposedly undistinguished film career. During this time, I’ve gained a greater understanding and appreciation of the performer who caught my interest in 1980, someone who has impressed me ever since with her confidence, charisma, skills, intelligence, wit and resilience. My hope is that this book does justice to her talents and achievements as both a film star and actor, while inspiring others to delve more deeply into her extensive film portfolio. For here remarkable things await discovery, even – or especially – in the very briefest of movie moments.

Be the first to write a comment.